This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Global Risk Governance in Health

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Epidemics know no borders and are often characterized by a high level of uncertainty, causing major challenges in risk governance. The author shows the emergence of global risk governance processes and the key role that the World Health Organization (WHO) plays within them.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Global Risk Governance in Health by N. Brender in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Global Development Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Thinking the International Response to a Global Health Risk

This chapter provides the theoretical basis for the empirical casework that follows. It firstly draws on the definitions of key concepts and theoretical elements presented in the literature review to provide the analytical framework on which this research is based. It then provides an overview of the process and key dimensions of the analysis of risk and the formation of an international response to it. It ends with a brief description of our approach.

Our framework is original in the sense that it introduces additional elements such as the notion of legitimate basis for the action of the multilateral institution and the existence of a risk assessment method, and it focuses on the existing and newly established risk assessment mechanisms and combines scientific risk assessment techniques with economics-based tools such as cost analysis in order to reach a more comprehensive approach. The combination of these elements allows for an evaluation of the quality of the risk analysis and, in turn, to determine whether these elements contribute to the quality of the response. Our framework borrows elements from both the technical approach to risk (in particular from the Red Book risk analysis framework) and business risk management techniques commonly used in companies, which consist of reducing uncertainty in order to understand more precisely and estimate the risk, thus allowing for more targeted action. In particular, the procedure of hazard identification, dose-response assessment, and exposure and risk characterization was used as guidance to analyze the activities of multilateral institutions, along with cost analysis, monitoring, evaluation of implementation problems, continuous improvement, and iterative characteristics of the business risk management process.

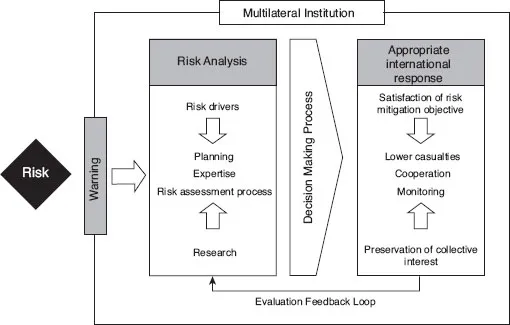

At a specific moment in time, one actor issues a risk warning. This actor may be an inside or outside agent of the multilateral institution, and its warning may or may not be revealed in the media.1 For the purpose of our study, we consider this warning that is captured by the multilateral institution as the triggering fact for the risk analysis process. This warning initiates the performance, within a multilateral institution, of a risk analysis in order to identify and evaluate the risk. The actors who participate in the risk analysis process, in identifying and evaluating the potential risk drivers and risk consequences, feed the risk analysis process with their theoretical and empirical knowledge. Risk analysis is based on a method, and it may take the form of an institutionalized, structured, and formalized process with predefined procedures, milestones, and requirements, or it may consist of a more informal and participative forum. Risk-related activities of multilateral institutions should appear legitimate to its members, thus relying on a formal agreement or recognition of action. The multilateral institution uses existing or establishes new risk analysis mechanisms in order to complete the risk assessment.

The process will result in a quantitative or qualitative estimation of the risk, or a combination of both, and a proposal of measures to be taken to reduce the risk. The appropriateness of this response that is provided by the multilateral institution will depend on the existence and the quality of the risk analysis performance. This response is designed to ensure the highest level of preservation of collective interest or, in other words, the highest level of risk reduction based on the information available at the time of the decision. The risk reduction level will translate into lower casualties in terms of impact on human lives, on other countries, and with respect to economic costs. This response should be the result of consultations that are formalized (documented), publicly communicated, and implemented. The implementation of the response is based on mechanisms that are internal and external to the multilateral institutions. While the multilateral institutions ensure the compilation and communication of information, regular reassessment of the issue and monitoring of the implementation of the response states are instrumental in reporting information to the multilateral institution and carrying out the measures that are recommended. Other actors such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or private companies can also contribute to the completion of the response.

The monitoring of the response’s implementation is a key element of the risk management process. Risk analysis is not linear, with a beginning (a risk) and an end (a solution to that risk). It is, rather, a continuous process of regular reassessment of the situation, the potential consequences, and the validity of the measures adopted in light of any new information acquired by the scientists and professionals dealing with that particular risk. Global risks often are characterized by uncertainty due to a lack of knowledge about the likelihood of occurrence of an event (e.g., the probability of a human influenza pandemic), its magnitude or damage (e.g., the number of persons infected and the number of deaths, as well as economic costs), its initial location, and its timing (where it could arise and when). Information about these elements may evolve over time and result in reviews of the previously adopted measures. These measures can be confirmed, modified, or canceled depending on the results of this continuous risk analysis.

The level of knowledge is not the only element driving this process. The success or the failure of an international response is another aspect of the continuous process. An evaluation of the response (whether the measures were applied and how effectively they were applied) should be performed to determine whether the objectives set have been met, not met, or partially met, and why. Measures that are not implemented or are partially implemented may be a sign that they are not accepted or understood by the concerned populations, are too costly, or are not adequate for the situation. The outputs of this evaluation should be used to feed the risk analysis process so as to continue to analyze the risk and formulate new responses. This continuous and iterative process can be illustrated as follows:

Figure 1.1 Iterative risk analysis process

1.1 Analyzing risk

Within this framework, risk analysis is based on the scientific assessment of an issue that ultimately aims to gain more knowledge about the issue and reduce uncertainties (whenever possible), including conducting a cost analysis and benefiting from the multilateral institution’s legitimacy of action. Risk analysis, for the purposes of this study, is defined as an expert-based deliberative and participative process that takes place within or under the lead of a multilateral institution, consisting of the performance of a scientific assessment of the risk according to a predefined plan or an organized method and addresses possible risk sources and their potential consequences and is characterized by three key dimensions: planning, expertise, and the risk assessment process. We will use these dimensions as key milestones to analyze each empirical case.

First, the planning dimension provides for the general conditions under which risk analysis can take place. It is composed of a predefined plan or an organized method, and rests on a legitimate basis for the multilateral institution’s action. The method that is used as the basis for the risk analysis can take the form of a conceptual formalized model (a predefined and documented risk analysis method, model, structures, and processes) or an empirical (and informal) method. This plan is built to track the risk, identify its source(s), and establish a risk causal chain. It can be inspired from existing frameworks such as the American National Research Council risk analysis framework (the Red Book risk analysis framework) or specifically designed for an institution. It also includes conventions and procedural rules, in particular addressing how to estimate the risk and accounting for uncertainties. (2 p. 13) The integration of lessons learned from past experience or from similar cases (if available) and the link to the potential consequences of the risk materialization can also be part of this method. The concrete application of this method should serve in conducting the risk assessment process. Examining the steps of the risk analysis process also can provide indications of the method applied, as well as oral comments about the risk analysis performance.

The legitimate basis for risk analysis under a multilateral institution refers to the notion of legitimacy, which gives rise to different interpretations in the literature. The legitimacy of an institution in its normative sense refers to the right to rule, and in its sociological sense to the belief in the right to rule. (22 p. 405) Multilateral institutions historically have derived their right to rule from international agreements. States delegate certain competences to the organization to issue rules and to ensure their compliance by the parties to these regulations. The IHR are an example of such agreements that confer rights to the WHO to use nonofficial sources to detect disease outbreaks and to issue recommendations to handle them. The European treaties also confer rights to the EU to issue regulations in specific areas, and the European Court of Justice represents one instrument of compliance available to the institution to ensure compliance with the European regulations. This legitimacy is important, as it defines the frame within which the institution can act, but the perception of other actors that the institution has the right to rule matters as well.

Believing that an institution is legitimate is an essential element in supporting its actions. Legally accepted bases for action are a necessary but insufficient condition of legitimacy. Formal legitimacy may be ineffective if no broad-based support from the public is associated with it. Keohane and Buchanan combine normative and sociological aspects to define legitimacy as “the right to rule, understood to mean both that institutional agents are morally justified in making rules and attempting to secure compliance with them and that people subject to those rules have moral, content-independent reasons to follow them and/or avoid interfering with others’ compliance with them.” (22 p. 411) We share with these authors the idea that formal delegation of competences granted to an organization is a necessary but insufficient condition for legitimacy. But focus remains the multilateral institution and the support granted to its action by member states, as states are considered the primary partners of the multilateral institution in implementing the response to a global risk, and stakeholders’ concerns are not analyzed here. Legitimacy essentially will be derived from the application and compliance by the states to the measures adopted by the multilateral institution.

Our approach considers both “rule-based” and “action-based” legitimacy. Legitimate bases for action are derived from two nonexclusive sources: the multilateral institution’s constitutive agreement (e.g., treaty or constitution), regulations, or rules accepted by member states, and generally accepted practices within a multilateral institution. For example, certain WHO practices in response to the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak, such as the use of nonofficial sources of information, generally were accepted by member states, although they were formally accepted as rules by the World Health Assembly later in the process, and then in the revised IHR in 2005.

Second, the expertise dimension combines the requirements for a diversified and internationally recognized background of the expertise involved in risk analysis, as well as the integration of the latest research, results in the risk estimation and proposition of measures. The background refers to the quality of scientific expertise involved in risk analysis, including the best-available scientific knowledge. There is no agreed-upon definition of expertise, but it seems generally accepted at the international level that it should be multidisciplinary and highly qualified in order to ensure that the best-available and more comprehensive scientific knowledge is used in a balanced way to analyze risk and propose measures. International expertise can be analyzed through excellence in performance or based on nomination. An expert is considered to be a skilled performer and recognized as an expert in his/her field. This recognition is based on several dimensions, including education, practical experience, and organizational role (23 p. 602).

In our approach, the quality of expertise is determined by its background diversity, which is defined by multidisciplinary, institutional, and geographical broad-based origin and an international track record. The combination of theoretical knowledge, knowledge of risk approaches (quantitative assessment and qualitative assessment such as scenario techniques), and past experience gained in different disciplines is considered to enrich risk analysis. For example, teams may be composed of individuals who are active worldwide in research institutions, universities, or laboratories, high-level professionals with field practical experience, internal expert officers working for the multilateral institution, and experts from other organizations. The review of the professional background, the institution of origin, and the country, as well as the level of experience of the key participants involved in the risk analysis process, will be based on public documents such as lists of participants, minutes, and reports regarding specific risk analysis meetings, complemented by interviews. The international track record of participants can be derived from the estimation for the group of the quantity and quality of international publications in peer reviews.

The research part of the expertise dimension is dedicated to the capacity of the multilateral institution to obtain and integrate the latest research results available into the response. It is important that the risk analysis encompasses the most recent research developments, particularly in the case of situations of uncertainty, when knowledge about the risk is progressing regarding the origin of the disease, its symptoms, its transmissibility, and its clinical course. Research findings can contribute to a more precise risk assessment that in turn may result in more targeted and effective measures. Evidence on how research is conducted to reduce uncertainty, the publication of results, and the integration of these results in recommendations can be found in meeting minutes, press releases, public communications, and documents of multilateral institutions and secondary sources that have analyzed the cases under study, as well as interviews. When available, it is also interesting to consider which resources were allocated to research and how they were split among the participants, when, and for which results.

Third, the risk assessment process dimension is composed of a series of steps that lead to the risk estimation and proposed risk management measures combining scientific assessment and cost analysis techniques. We consider the presence of an observation system, risk analysis mechanisms, and cost analysis as essential components of this process. The risk assessment process relies on the presence of a continuous observation system that reports information on a regular basis about risk issues that serve as a basis for the risk analysis. This system may report a warning concerning a potential risk or a new risk, and the development of that risk. This observation system (also called surveillance system) can be human or system based, or both. It may encompass different mechanisms and tools in order to achieve its mission of providing information. For example, it can take the form of computerized surveillance systems that compile facts reported in a particular field (such as disease outbreaks), human activities of observation in the field, or an international forum for professionals who exchange knowledge about a particular issue. This observation system can be internal or external to the multilateral institution, or a combination of both. The Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN), which represents one element of the WHO observation system, provides this organization with information about disease outbreaks that occur worldwide.

Risk assessment mechanisms mainly relate to how risk analysis is performed in terms of activities, resources, and tools. Risk analysis mechanisms consist of activities carried out to identify the risk source(s) and evaluate the relationship between the risk source(s) and the potential consequences of the risk, including the determination and exposure of the populations at risk. These activities should result in an estimation of the probability of occurrence and the seriousness of the consequences of the risk, a communication of uncertainties, and a proposal of measures to reduce the risk. The mechanisms are often contained in the risk analysis method, but can also be a current practice that is not documented. They also can be adapted or customized upon the identification of a new risk. Risk assessment mechanisms are mainly science based and may operate using different tools...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Thinking the International Response to a Global Health Risk

- 2 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome: Analysis of a Successful Containment

- 3 Avian Influenza H5N1: International Preparedness against a Future Influenza Pandemic

- 4 Cases Comparison, Outlook on H1N1 Influenza Pandemic, and Conclusions

- Notes

- Bibliography

- References

- Index