This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Changing Geography of International Business

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Presents papers which grapple with some of the most important developments and challenges in International Business, both for the firms who must fashion strategy within a rapidly changing world economic order and researchers who seek to explain the nature of these shifts and how firms respond.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Changing Geography of International Business by Gary Cook,Jennifer Johns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Flatness: The Global Disaggregation of Value Creation

Ram Mudambi

Introduction

At the most general level, the idea of ‘flatness’ in the context of economic development has to do with parity. This is the property whereby different individuals or areas of the world are roughly similar in terms of their levels of economic outcomes. Thus, in comparing one individual or area to another, the observer perceives similarity in terms of measurable outcomes like standards of living and incomes.

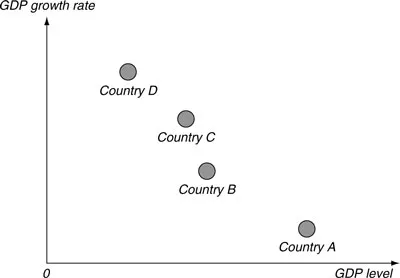

Academics see the approach to flatness as a part of the process of convergence. Theoretically convergence is occurring if the relationship between a measure of the level of economic outcome and the rate of growth of economic outcome is downward sloping. Thus, if we use gross domestic product (GDP) as the measure of economic outcome, a situation where high GDP countries witness relatively slower rates of growth than low GDP countries is associated with convergence. The greater the difference in growth rates, the more rapid the convergence (Figure 1.1).

On the other hand, popular writers see flatness more anecdotally in terms of the ‘see, touch, feel’ of locations. Thus, convergence is seen as occurring when the nature of consumption and service availability becomes similar across locations, regardless of the extent of diffusion of these within the mainstream economy (Friedman, 2005).

The nature of the world economy and the extent of parity across countries and regions has been changing dramatically over the last few decades. In this essay, I will argue that this can be best understood by considering three worlds. The first is the pre-industrial world of the distant past characterized by an extreme lack of parity both across and within countries and regions. The second is the world of yesterday, a period beginning with the Industrial Revolution, during which rough parity or flatness was established within certain regions and countries of the world. The third is the evolving world of today and the future, a period beginning about three decades ago, when large new economies began to emerge in the sense of becoming integrated in the world economy.

The world of today is one where the flatness that was established within many wealthy industrial countries (Pomfret, 2011) is under threat, as many economic activities, especially those involving low knowledge inputs, migrate to emerging economies. At the same time, emerging economies are seeing the appearance of large and rapidly growing middle classes springing from their formerly homogeneous or ‘flat’ poverty-stricken masses. These new moneyed classes are being nurtured by the same economic activities that are migrating out of wealthy, advanced economies, some of which are even expanding the local (previously tiny) wealthy elites. A new form of parity or flatness is appearing that is not based on geography or location, but rather on human capital and skill levels.

Figure 1.1 Convergence

The distant past – a local world

The world before the Industrial Revolution was made up of economies dominated by agriculture and craft manufacture. It was a world where all economies were composed of very small leisure classes and where the vast majority of the population of even the wealthiest economies of China and India lived in abject poverty (Maddison, 2007). There was a large gap between the miniscule population of ‘haves’ and the vast population of ‘have-nots’ in every location on the globe. Most of humanity was mired in a subsistence existence. It would be fair to say that this parity or flatness was a sub-optimal state of affairs for most, if not all of humanity.1

Both production and consumption were largely local. Few individuals travelled beyond their immediate neighbourhoods and all were completely dependent on indigenous systems for their needs. The international transport of luxury items through desert caravans and long, risky sea voyages has been celebrated in song and story (Mark, 1997; Wellard, 1977), but it made up a tiny proportion of total consumption of even the very wealthiest individuals.

The world of yesterday – trade in goods

The first two centuries after the advent of the Industrial Revolution were characterized by urbanization, that is, the growth of cities as industrial centres. These industrial cities were connected to their immediate hinterland, and over time, to a national production and innovation system by both physical and institutional infrastructure. Systems of production remained largely local as illustrated by the classic von Thünen (1827) model.

International trade increased by fits and starts over the two-century period between the mid-eighteenth and the mid-twentieth centuries. To a large extent, the Ricardian principles of comparative advantage prevailed throughout this period. Thus, countries specialized in the production of particular goods and services and the trade that occurred was largely in terms of final (finished) goods. These goods were mostly produced in local systems of production (Belussi, 1999). They were local in the sense that most of the industrial or manufacturing activities, both those with high- and low-knowledge intensity, were undertaken within concentrated geographical spaces, mostly in advanced industrialized countries.

Further, in these advanced industrialized counties, local redistribution of wealth (eventually) occurred through trickle-down and more formal redistributive schemes like taxation. The dominance of local systems of production (and in particular, local labour markets and unions) ensured that low-skill individuals in high-productivity countries could enjoy disproportionately high standards of living due to the prevailing high level of spatial transaction costs (Beugelsdijk et al., 2010; Dunning, 1998; McCann and Shefer, 2004; Storper and Scott, 1995).2 To some extent they could free-ride on the knowledge and value created in the jurisdictions within which they lived (a) directly through wages that were high relative to their skills; and (b) indirectly through enjoying public goods and services created from tax revenues on high local productivity. Thus, for most advanced economies, the twentieth century became the ‘age of equality’ (Pomfret, 2011).

The cohesion of these local and national production and innovation systems (Lundvall, 2007) led to a convergence of local, corporate and national interests. Workers, stockholders and taxpayers all felt a common bond of shared self-interest based on their geographical colocation. Improved performance of locally based corporate entities increased local employment and wages, increased the wealth of local stockholders and boosted local tax revenues, enabling the provision of more and better public services. Thus, it was possible and even essentially correct for General Motors chairman Charles Erwin Wilson to say at a Senate hearing on his confirmation as Secretary of Defense in the Eisenhower administration in 1953 that he faced no conflict of interest since ‘what’s good for General Motors is good for the country’.

These local systems of production and national systems of innovation came into being due to high spatial transaction costs and were reinforced over time by layers of national institutions (Mudambi and Navarra, 2002). As intra-country income and standards of living grew more ‘flat’ in most of the developed or so-called ‘first’ world, the gap between industrialized and agrarian and primary goods-producing countries grew.3 Corporate entities in industrialized countries had little interest in the knowledge resources in these developing countries, since the cost of leveraging them was just too high.

The consequences of the world of high spatial transaction costs and consequent locational aggregation of economic activities were unambiguous. Incomes and standards of living were determined by geography and location than by human capital and skills. It was a world of global disparities and the division of the world into ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ countries. In the world of yesterday, it was considered the norm for an assembly line worker in Detroit with an eighth-grade education to earn more and enjoy a higher standard of living than a brain surgeon in New Delhi.

The world of today – trade in activities

The key change that has been occurring over the last three decades is the inexorable decline of spatial transaction costs. This is a process that has been unfolded over several decades and is made of too many different factors, advances and innovations to examine each in detail. Suffice it to say that they are concentrated in the areas of logistics and information and communications technologies (ICT) and include:

• Improved international shipping and logistics including containerization

• Just-in-time systems involving increased and improved buyer–supplier coordination

• ICT beginning with facsimiles and continuing through email and web-based enterprise resource planning systems.

The best way to understand the evolving modern economy and the transformation from the world of yesterday dominated by trade in goods into the world of today based on trade in activities is through the tool of global value chains (GVCs).

Global value chains

Value chain analysis is an innovative tool that views the economy in terms of activities instead of its constituent industries and firms (Mudambi, 2008). A value chain for any product of service consists of a number of interlinked activities extending from ideation and upstream R&D to raw materials and component supply, production, through delivery to international buyers, and often beyond that to disposal and recycling.4

Modern value chain analysis enables us to pinpoint the relative contributions to value creation associated with each activity, from basic raw materials to final demand. This approach helps us to understand that as far as geographic location is concerned, success in terms of creating prosperity is based on the local activities performed rather than the identity of local firms or industries.

Drastically reduced spatial transaction costs make it feasible to disaggregate the firm’s business processes into progressively finer slices. Firms are able to specialize in increasingly narrow niches, which need not even be contiguous in the value chain (Mudambi, 2008). This makes it crucial for the firm to identify the process activities over which it has competitive advantage, since these are the basis of the firm’s core competencies that enable it to generate rents (Hamel and Prahalad, 1990).

The importance of fragmented production and intermediates trade has been widely documented in academic research (e.g., Baldwin, 2006). When trade is disaggregated and geographically dispersed across national borders, a GVC exists. GVCs incorporate all the activities related to producing a good or service and delivering the product or service to the end user.

The implications of GVCs

Viewing the world economy through the lens of GVCs makes it possible to make analytical comparisons between yesterday’s ‘trade in goods’ and today’s ‘trade in activities’. Coasian transaction costs determine the boundaries of the firm, that is, they underpin the control decision in terms of activities that are retained in-house versus those that are outsourced. In the same way, spatial transaction costs determine the location of activities in terms of concentration versus dispersion. As spatial transaction costs fall, the optimal level of dispersion of economic activities over geographic space rises. In other words, the lower the spatial transaction costs, the more likely activities are to be performed in their most efficient locations.

In yesterday’s world of high spatial transaction costs, the optimal strategies for firms, including multinational enterprises (MNEs), involved a significant concentration of economic activities in their home countries, with trade carried out largely in terms of finished goods. This is the world of Ricardo and it persisted more or less intact through most of the twentieth century. However, beginning about three decades ago, spatial transaction costs began to fall, slowly at first as regional trade agreements in Europe and North America increased the attraction of moving activities rather than finished goods from the home country to the host country.5

This activity dispersion began to accelerate as technology made it possible for outsourcers as well as a firm’s foreign subsidiary units to undertake increasingly sophisticated activities while remaining closely embedded within the parent firm’s corporate network (Anderson, Forsgren and Holm, 2002; Meyer et al., 2011). The movement of knowledge activities to high-skill, low-cost labour MNE subsidiaries set in train a virtuous cycle of value creation in many of today’s emerging economies. Knowledge spillovers from these MNE subsidiaries into the local economy occurred through numerous channels, including labour force turnover and the training of suppliers and local partner firms. In time, these spillover processes spawned populations of local firms intent on catching up with the global industry leaders based in market economies. Finally, pressure from these new and aggressive emerging market MNEs, the so-called EMNEs, is a factor in the increased pressure to innovate and develop new industries in advanced market economies. These three processes of spillover, catch-up and industry creation are driving the changing geography of value creation in the world of today and the coming decades (Mudambi, 2008).

Concluding remarks – flatness tod...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: The Changing Geography of International Business

- 1. Flatness: The Global Disaggregation of Value Creation

- Part I: Institutional Perspectives on International Business

- Part II: International Business Activities Across Different Spatial Scales

- Part III: Placing Multinational Enterprise Activities

- Index