eBook - ePub

The Political Economy of Agro-Food Markets in China

The Social Construction of the Markets in an Era of Globalization

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Political Economy of Agro-Food Markets in China

The Social Construction of the Markets in an Era of Globalization

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

China's agricultural production and food consumption have increased tremendously, leading to a complete evolution of agro-food markets. The book is divided into two parts; the first part reviews the theoretical framework for the 'social construction of the markets, ' while the second part presents the implication for the agro-food markets in China.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Political Economy of Agro-Food Markets in China by L. Augustin-Jean, B. Alpermann, L. Augustin-Jean,B. Alpermann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Theoretical Foundations of Agro-Food Markets

1

Markets as Political Institutions

Andy Smith

1.1 Introduction

Economic sociology has convincingly shown markets to be structured by socially constructed sets of institutions, i.e. stabilized systems of rules, norms, and expectations (Hall and Taylor, 2009). Indeed, Neil Fligstein (2001) in particular has shown that markets would simply not exist in any durable form without the ‘architecture’ provided by these institutions. Notwithstanding the considerable contribution of this research tradition to knowledge about economies, to date its primary focus has not been upon precisely who produces these institutions, how, why and to what effect. More specifically, what forms of argumentation and which material or positional resources enable certain actors to dominate the making and implementation of these institutions? In short, how are markets and their institutions politically constructed?

Drawing upon sociological approaches to political science and lengthy collaborations with industrial economists (Jullien and Smith, 2008a and 2011), Part I of this chapter sets out a generic approach to markets as institutions. This is extended in Part II in order to provide theory-driven answers to the questions raised above, and this by revealing the ‘political work’ that produces and reproduces market institutions within specific industries. In so doing, a series of questions will be raised regarding how the conceptual framework proposed could help to guide research on China’s agro-food markets. The third part of the chapter deepens this reflection about the institutional isomorphism or singularity of Chinese agro-food sectors by emphasizing the transnational and interdependent character of much of the contemporary institutional ordering of markets. More specifically, the question raised and framed conceptually concerns the degree to which components of agro-food industries are now structured by global institutions which also have deep impacts upon Chinese agriculture and agribusiness. Emphasized more fully in the piece’s conclusions, the overall argument of the chapter is that the political, economic and sociological dimensions of agriculture, food, and their respective markets simply must be studied simultaneously, but that this can only be achieved by developing appropriate theories and research methods.

1.2 Markets, industries and institutions

In keeping with many common usages of this term, markets are indeed actual or virtual sites of human interaction through which goods or services are bought and sold. However, as the introduction to this book underlines and explains, this does not mean that markets themselves are actors nor, consequently and contrary to popular opinion, do they ever ‘decide’. Instead, each market is a structured mechanism through which transactions take place and, in most instances, are rendered durable because the market’s institutions reduce uncertainty and encourage sufficient levels of trust. Whether they take the form of a legal rule, a social norm or simply a codified expectation, the institutions of a market thus encourage producers and sellers of goods to develop medium- and long-term strategies, and thence to invest money, time, energy, and hope in their respective business activities (Williamson, 1985).

However, the durability of markets cannot be fully understood by considering that each stakeholder constantly makes ‘rational calculations’ about whether to obey their institutions on the basis of how much they lower uncertainty. Instead, the long life of most markets and their institutions is more deeply and sociologically explained by considering that their legitimacy stems from their inscription within domains of collective action I call industries. Like other researchers who label these domains ‘fields’ (Fligstein, 2001), ‘sectors’ (Hassenteufel, 2008), ‘value chains’ (Gereffi and Korzeniewicz, 1994) or ‘trading systems’ (Wolfe, 2005), I consider that markets are just one important part of each mode of interdependence that has been developed over time around the production and commercialization of a good or a service. In keeping with all of these literatures, I therefore consider that an industry is an institutionalized set of rules, norms, and expectations on the one hand, and of a hierarchy of actors on the other. Moreover, my attempt to conceptually resuscitate the term ‘industry’ seeks to go beyond two limitations of existing approaches to the political economy of markets.

The first concerns the component parts of an industry, as well as its connection with other parts of the economy. Rather than continue to think about industrial activity as a linear set of sequences between production and sales, it is crucially important to conceptualize each industry as an ‘Institutional Order’ of interlocking institutions which, whilst developing a certain level of autonomy, is firmly articulated to other such orders.

The second limitation of the existing literature is that it almost invariably posits a distinction between business and political activity. This dichotomy then reifies representatives of the former as endogenous actors whilst reducing politicians and administrators to exogenous variables. The conceptualization of an industry proposed here abandons this misleading simplification by including the second category of actors as stakeholders within the industry and, more fundamentally, by developing a more analytical definition of ‘politics’ in the section that follows this one.

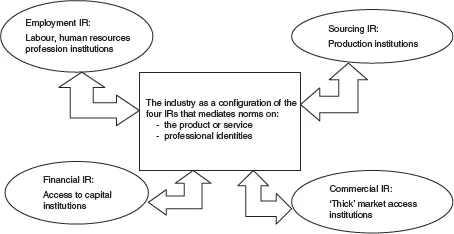

To move beyond these blindspots on political economy generated by linear thinking about industrial activity and the binary, formalistic distinctions that so often accompany it, the first required step is therefore to consider that the Institutional Order (IO) of each industry has been constructed around four groupings of perennial economic issues: finance, employment, sourcing, and commercialization. As Figure 1.1 seeks to visualize, in order to be stabilized and reproduced each of these groupings generates an Instituted Relationship (IR) which research must unpack both individually and in terms of its articulations with the other three IRs (Jullien, 2011).

Figure 1.1 An industry as an institutional order of four instituted relationships

What are the implications of considering that these IRs are made up of institutions and, indeed, are themselves institutions?

Overall, this signifies that in keeping with all such institutions (Hall and Taylor, 2009), IRs contain elements that structure the behaviour of actors due to their stability, density, and pervasiveness within the industry concerned. For this reason, research needs to generate information about the range of collective and public policy instruments and, above all, how they have been institutionalized over time, by whom and to what end.

In the case of an industry’s Finance IR, its institutions typically include those that govern access to capital, i.e. banks, stock exchanges, public investment funds, family savings, etc., and the restraints placed thereon in the form of taxes, interest rates, and a myriad of detailed rules covering debt ratios, mergers, accounting standards, ‘transparency’, etc. For example, research has shown for many years that although sharing the same category, banks throughout the world and over time have developed very different practices and rules for dealing with public and private companies (Zysman, 1983). Indeed, much of the ‘success’ of German companies has often been attributed to the long-term relations they develop with their respective banks, just as the intensification of French agriculture since the 1960s cannot be fully understood without analysing the role played by one bank in particular: Le Crédit Agricole. More generally, recent research has focused more on the rise of venture capital markets in Europe and the US and their impact upon older stock exchanges (Posner, 2009). One would expect studies of industries in China to focus in particular upon the ‘hybrid’ inter-relationship between public and private sources of finance, as well as the influence of state financial planning (see, for example, L. Augustin-Jean’s analysis of the Chinese sugar industry, 2010). Whatever the industry or polity a company is operating in, however, what counts from the point of view of the politics of political economy is that research sets out to capture the key sources of capital involved as well as the principal institutions which enable it to be generated and deployed, but also set limits upon these practices.

If capital is the lifeblood of an industry, then its employees are its brain and muscles. Although today in a widely deindustrializing Western Europe the importance of labour tends to be downplayed and seen chiefly as a costly constraint upon domestic production, the availability of people to produce and sell goods and services remains a vital dimension of any industry in any polity. Consequently it is important not to reduce the Employment IR uniquely to the cost of labour. Of course, levels of wages and social protection vary enormously across the globe, and this clearly has a heavy impact upon where goods and services are currently produced. The rules and norms that govern the employment of workers must therefore be given great importance by political economy. However, at least two other aspects need treating simultaneously. The first concerns labour market policies such as training, career guidance and more generally the educational practices which orientate individuals towards certain occupations rather than others (Maurice, Seiler, and Silvestre, 1982; Culpepper, 2003). For example, I live in the most prestigious wine-making area in the world – Bordeaux – but it currently faces a shortage of qualified tractor drivers that a range of professional and public bodies are attempting to address through pro-active policies. The second, and even more neglected, aspect of the Employment IR that needs studying is the roles of professions within an industry. These institutionalized categories can have a highly structuring impact upon the political objectives adopted, as Arnaud Sergent has shown, for example, in recent research into the French forestry industry by revealing the evolving role played by a corps of state managers (2012). In short, and to return to the case of industries in China, the commonly held view in the West is that companies in that country are currently doing so well primarily because of the low cost of its labour. However, there are no doubt also more subtle reasons for this ‘success’, which are linked to other aspects of employment over which a more comprehensive and dynamic approach to this IR would guide research to generating deeper and more interesting knowledge (e.g. the role of regional government in financing training (Xu, 2009) or the role played by agricultural cooperatives: Augustin-Jean and Xue, 2011).

If capital and labour have been studied intensely by specialists of political economy, the same cannot however be said for aspects of this subject area that are categorized here within the Sourcing and Commercial IRs. The former encompasses all the rules and norms that determine how a good or service is produced and processed. In the case of the European Union’s (EU) wine industry, for example, the Sourcing IR includes institutionalized definitions of the product itself (e.g. rules on added sugar and other ingredients), significant parts of its official categories (e.g. Appellation d’origine contrôlée: AOC), where vines can be grown, and maximum yields. In the case of the EU’s beef industry, this IR features rules regarding the rearing of cattle, their slaughtering, and the processing of meat. Of course, the general supposition is that rules of this type are particularly prevalent in Western Europe due to the combined weight of interventionist-state histories and the effect of the EU’s ‘single market’ upon standard-setting as a tool against protectionism. However, sourcing institutions and IRs clearly exist in many other countries, notably the US and Japan, and thus always have an impact on both the orientation and costs of production on the one hand and international trade on the other (see Part III). Again, researchers new to China would spontaneously hypothesize that the Sourcing IR of industries in that country are less dense than in the above-mentioned countries. But closer examination would probably reveal that this is not always the case and that, in any event, the sourcing of goods and services in China now tends to fall in line with, or at least translate, international standards much more often than was the case a decade ago (see, for example, research findings on the establishment of geographical indications in that country: Wang, 2012).

The fourth and final IR concerns market access and marketing. Like its Sourcing counterpart, this Commercial IR has rarely been directly examined in detail within the political economy. Indeed, perhaps because part of this subject area has implicitly been delegated to business studies and their specialists of marketing, the fundamental question of how products and services reach the marketplace to be bought by consumers is under-theorized and under-studied. Rather than reduce market access to the thin notion of tariff barriers, as many lawyers and the World Trade Organization (WTO) tend strongly to do, here the Commercial IR is given a more extensive meaning so as to include a wider range of institutions which permit or forbid, encourage or discourage, a product or service from reaching an interface with consumers. For example, in the case of the agro-chemical industry one needs to include here norms regarding intellectual property rights (IPR) and market authorizations which, in the EU and North America, have become increasingly difficult to obtain. In the case of wine, labelling laws, IPR again through other institutions of geographical indications, and distribution networks all necessitate data generation and analysis. Again, one might be tempted to assume that institutions which set constraints upon where, when, and how a product or service can be sold will have a more signi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Agro-Food Markets in China in Light of Economic Sociology

- Part I The Theoretical Foundations of Agro-Food Markets

- Part II From Producers to Consumers: The Market for Food Products

- Part III From Farm to Factory: Fibres and Biofuels

- Conclusion: Economic Sociology and the Political Economy of China’s Agro-Food Markets

- Index