eBook - ePub

Software Business Start-up Memories

Key Decisions in Success Stories

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Describes the decisions that led to the success of 16 software companies. The decisions are illustrated in detail, providing entrepreneurs with insights into what it takes to make a decision that can change the future of a company.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Software Business Start-up Memories by S. Jansen,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

The majority of software start-ups between 50 and 80 percent fail during the first five years of their existence (Busenitz, 1999; Nowak & Grantham, 2000). So what is it that these companies neglect doing on such a massive scale that the few successful companies distinguish themselves with? This question is more important now than it has ever been, due to the large number of competitors in the software market, facilitated by the low threshold that the emergence of the internet and related technologies bring (Nowak & Grantham, 2000). Together with the economic downturn, this has resulted in a growing popularity of entrepreneurship. The lack of experience of these entrepreneurs only increases the number of businesses that do not even survive their start-up period.

While there are a few hints as to what makes an entrepreneur successful, such as motivation, it is currently still impossible to properly explain what causes a company to grow and therefore survive. An understanding of the core success-factors of software entrepreneurs is critical for the stimulation of economic growth (Nowak & Grantham, 2000). Despite the highly fragmented field of entrepreneurial research focusing on predicting start-up success, it has proved, as of yet, to be impossible to identify universal success-factors (Lechler, 2001). Extensively researched areas include entrepreneurial characteristics (Stevenson & Jarillo, 1990), properties (Duchesneau & Gartner, 1990; Westhead, Ucbasaran, & Wright, 2005) and heuristics (Busenitz, 1999). By focusing on the early-life decisions, instead of specifically trying to identify universal success-factors, we aim to provide a unique insight into the lives of software entrepreneurs and how they achieved their success. The identified early-life decisions that have played a large role in the success of established software companies in the Netherlands could make new entrepreneurs aware of the critical areas of their business. These areas can then be given extra attention to increase the possibility of success. Compared to the success stories of specific companies, which describe the history of a company, these decisions have a more practical application to nascent entrepreneurs since they do not only describe a single case, but are also compared and analyzed in relation to decisions made in other companies. Since all decisions are made in roughly the same period of the company lifecycle, we provide valuable insight into the areas of the business, and the specific decisions made in those areas, that might assist nascent entrepreneurs in building a successful software company.

While the main focus is on the decisions that contributed to the success of the company, for the majority of the identified decisions, the entrepreneurs have also elaborated on the results they delivered and their motivation for making these decisions. Most of the entrepreneurs have also elaborated on a number of decisions that were detrimental to the success of their company, but luckily not so severe as to lead to their company’s failure. We have conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews with founders from 16 different Dutch product-software companies, situated in different parts of the Netherlands. In a few cases where the founder was not available, the current CEO with intimate knowledge about the start-up phase of the company was interviewed. The selection criteria for these companies were as follows:

• They should be Dutch and need to be active in the Dutch market.

• They should be at least five years old, since this is generally the accepted length of the start-up period of a company (Busenitz, 1999; Nowak & Grantham, 2000; Schutjens & Wever, 2000). Surviving these first five years can be seen as critical for a company to become successful.

• They should have at least 50 employees to ensure that we attract the more successful companies. This is also commonly, both by scientific literature as well as practice, seen as the cutoff point between small and medium-sized companies (see for instance European Commission, 2003).

• They should have been profitable for a number of years.

• They should add value to their customers, which in practice means we focus on product software for business environments.

Due to the size of the software industry, a small increase in the number of software entrepreneurs that become successful by focusing on the identified early-life decision areas could greatly influence both national and international economies.

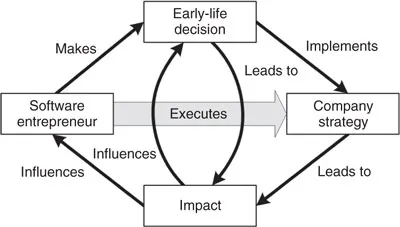

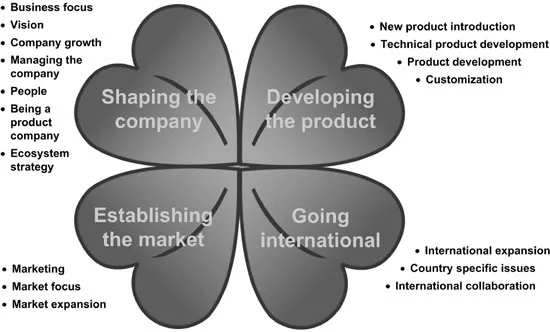

Two models are used to guide the description of the success decisions: the software start-up decision model (Figure 1.1) and the early-life decision model (Figure 1.2). The first model explains how to relate the decisions a software entrepreneur makes to the company strategy and its impact. The second and most important model of this book, categorizes the different decisions, to provide software entrepreneurs with an overview of the decisions that they can make.

Figure 1.1 Software start-up decision model

1.1 The software start-up decision model

The software start-up decision model, Figure 1.1, illustrates the relations between the entrepreneur, the company strategy, the early-life decisions, and the impact of these decisions. This model shows how a software entrepreneur executes the company strategy, by making an early-life decision to implement a certain company strategy. This strategy – just as the decision itself – leads to a certain impact on the company. This impact influences the future decisions that software entrepreneurs make. Decisions that do not result in an observable change of any kind do not fall into the category of an early-life decision and are therefore not reported in this book.

An example of such a decision is the decision of the founders of e-office to run their company without any structure. This decision was made because they believed this was the best way to empower their employees and therefore enable optimal knowledge- and information-flow among their employees. It was this company strategy that was implemented by the decision. The impact of the decision was that it led to chaos within the company and bankruptcy would eventually have been inevitable without changes. This impact influenced the software entrepreneur, the founders of e-office, to make another decision: to run their company in a structured manner. The experiences of the unstructured work environment proved not to work, influencing the entrepreneurs to make a different decision. The goal of this decision, the company strategy to optimize the knowledge and information flow among their employees, was the same. The result of this decision proved to be toxic to what the founders call ‘the power of people’, which influenced the entrepreneurs to find an optimal middle-ground between these two extremes. This is a nice example of how by wanting to execute one small part of a company strategy, multiple decisions can be taken, each leading to a certain impact and influencing the entrepreneur in the decision making that follows.

Figure 1.2 Early-life decision model for software entrepreneurs

1.2 The early-life decision model

The most important model used in this book is the early-life decision model, as shown in Figure 1.2. It categorizes the successful decisions software entrepreneurs can make. From the interview data, 17 different decision types have been identified and grouped into four decision categories. Entrepreneurs can use the model as a reminder of the different types of decisions that are most critical to achieving company success. Entrepreneurs should therefore be aware of these decision types in their day-to-day decision making. Each leaf of the four-leaf clover, chosen because a quarter of the entrepreneurs mentioned that luck also influenced their success, indicates one of the decision categories. The bullet points that are situated beside the leaves are the 17 different decision types that belong to the corresponding decision categories. The order of the decision types in their categories is determined by how frequently the decision types were found in the case studies. This acts as an indication of the importance of the different types within each category.

Chapter 2 describes the theoretical background from literature that relates to the decision making of entrepreneurs. The theories discussed in Chapter 2 are used to analyze the data from the interviews. Chapter 3 contains a short introduction to the company descriptions, which can be found in Chapters 4–19. Chapters 20 and 21 contain the analysis of the interview data, and Chapter 22 some discussion, after which conclusions are drawn in Chapter 23.

2

Theoretical Background

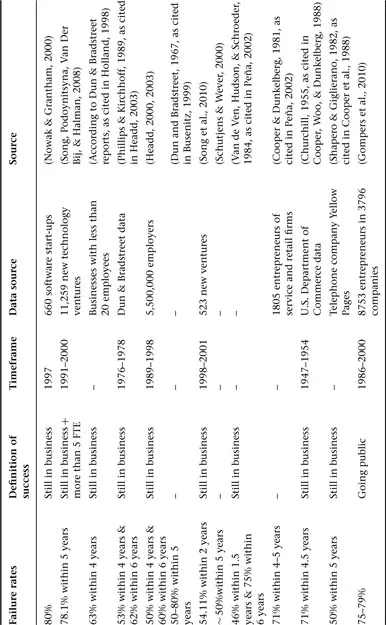

With more and more technologies available via the internet, large markets are within easy reach for software producers (Nowak & Grantham, 2000). The downside of the emergence of the web in this respect is that the threshold for new entrants is radically lower than ever before, leading to more competition within the software market. This high level of competition in the software market consequently leads to the likelihood of more failures, even though only 19 percent of all nascent entrepreneurs want to become rich and establish a large company (Van Gelderen, Thurik & Bosma, 2006). To stimulate economic growth, it is critical that the basic success factors of software entrepreneurs are understood (Nowak & Grantham, 2000). Although different authors define the success of a company differently, numerous studies show that 50–80 percent of new businesses fail during their start-up period, which is generally defined as the first five years of the company (Dun and Bradstreet, 1967, as cited in Busenitz, 1999; Headd, 2000, 2003; Nowak & Grantham, 2000). Table 2.1 shows the different failure rate percentages identified by different authors. Gompers, Kovner, Lerner and Scharfstein (2010, p. 26) are at the high end of these estimates, claiming that ‘first-time entrepreneurs have a 20.9% chance of succeeding’. This percentage can increase to 25 percent when the entrepreneurs have precious entrepreneurial experience. It is worth noting, however, that the definition of success used in this study is going public with the company, where the general definition is ‘still being in business after approximately five years’. Song, Song and Parry (2010) suggest that the failure rates of new companies go up in times of economic downturn. These failure rates can be seen as alarming, since small companies make up by far the largest portion of total employers, 99.7 percent in the United States and 96 percent in Australia, not considering agricultural businesses (Morrison, Breen & Ali, 2003). Additionally, only 1 percent of all businesses in Europe employ more than 50 people. The main reason for these high failure-rates according to Hoch et al. (2000) is the incredible speed at which technological innovations are realized. Not being able to keep up with your competitors in technological innovations will inevitably result in failure, regardless of how good your product is (Hoch et al., 2000).

Table 2.1 Failure rates in start-ups

Of around 700,000 new companies being started each year in the United States, only 3.5 percent eventually grow to become a large company employing more than 50 people (Gilbert, McDougall & Audretsch, 2006). This finding, that 700,000 new companies are started every year, averages to almost 1918 new companies each day. The study of Osborne (1995) showed that 1000 companies fail every day in the United States. Of these companies, only a few managed to stay in business for longer than five years before they failed. Carter, Gartner and Reynolds (1996) mention that almost 4 percent of American adults of working age will be involved in founding a company sometime during their lifetime.

While entrepreneurs create more jobs when starting their own company compared to working at a company as an employee, entrepreneurs tend to pay lower wages, offer fewer benefits, and their jobs are more dynamic, leading to unstable jobs (Van Praag & Versloot, 2007). This suggests that, even though the wages and benefits are lower and jobs are unstable, an entrepreneur who starts his or her own company is making a positive contribution to the job market. Even with all these downsides that accompany working for an entrepreneur, Van Praag and Versloot (2007) found that job satisfaction is higher among employees working for an entrepreneur compared to that of employees who work for a stable and established employer. The same study indicated that the results are the same for the entrepreneurs: they experience a higher job satisfaction starting their own business, even though they would be able to make more money working for an employer.

Entrepreneurs are often found to lack knowledge in key disciplines like business planning, competitive assessment, marketing, sales, human resources and financial planning (Nowak & Grantham, 2000). Serious errors in any one of these disciplines can cause a company to fail. It is however impossible to create a standardized list of actions or criteria that will lead to success (Carter et al., 1996; Low & MacMillan, 1988).

One of the reasons why it is impossible to create such a list of actions or criteria, is the fact that entrepreneurial literature already conflicts on seemingly simple aspects, such as the influence of having a business plan on the new venture success (Duchesneau & Gartner, 1990; Van Gelderen et al., 2006; Schutjens & Wever, 2000). While several authors (Osborne, 1995; Rea, 1989; Taylor & Seanard, 2004; Timmons, 1982) state that it fosters success, other researchers ‘concluded that having a business plan was no guarantee of success’ (Schutjens & Wever, 2000, p. 138). The advantages of developing a business plan are identified as the ability to maximize the timing and location of market entry (Taylor & Seanard, 2004) – which could lead to easier and faster acceptance of the market and thus higher sales – and to structure and focus the activities of the entrepreneur (Van Gelderen et al., 2006) – leading to higher productivity. The latter authors found that the effect of writing a business plan depends on the ambition the entrepreneurs have. For entrepreneurs with low ambition, writing a business plan has a positive effect, while it works negatively for entrepreneurs with higher ambitions. If the entrepreneurs with a high ambition write a business plan in a later stage of starting a business, it does have a positive effect on the company (Van Gelderen et al., 2006). From the results of Van Gelderen et al. (2006), we can conclude that writing a business plan will always be positive, that the question should not be ‘Do I write a business plan?’, but ‘When do I write a business plan?’ Van Gelderen et al. (2006) explain that the reason that a business plan has a positive impact on small businesses is that it provides the entrepreneurs with a structure and focus with regard to their activities. Their explanation is that people who start a large business will usually have enough experience and knowledge to not need a business plan in the early stages of the business. Although the majority of new businesses do not have a written busin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Theoretical Background

- 3. Lessons of Software Entrepreneurs

- 4. AFAS

- 5. DBS

- 6. Noldus Information Technology

- 7. Exact

- 8. Stabiplan

- 9. Sofon

- 10. GX Software

- 11. Pallas Athena

- 12. ORTEC

- 13. e-office

- 14. ChipSoft

- 15. Syntess Software

- 16. Planon

- 17. Ultimo Software Solutions

- 18. Centric

- 19. UNIT4

- 20. Decision Categories

- 21. Decision Analysis

- 22. Conclusion

- Appendix – Early-life decisions overview

- Notes

- References

- Index