This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

How do bank supervisors strike a balance between market self-regulation and pro-active regulatory intervention? This book investigates the choice of banking supervision approach in four European Union member states from Central and Eastern Europe – Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, and Slovenia – after their transition to democracy and market economy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Regulating Banks in Central and Eastern Europe by A. Spendzharova in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Quest for Financial Stability: Determinants of Regulatory Approach in Banking Supervision

Does Counter-Cyclical Regulation Play a Role?

Section 1.1 Research design

Effective banking supervision is important for ensuring financial sector stability. A country’s choice of banking sector regulatory approach has an impact on banks’ lending decisions and the overall availability of credit in the financial system (Greenwald and Stiglitz 2003: 5–8). Market-based regulation was prevalent in the decades leading up to the 2008 global financial crisis. This approach is based on the assumption that if sufficient information is available on the marketplace, market discipline will force financial actors to behave responsibly, and will thus promote financial stability (Barth et al. 2006; Wymeersch 2009; de Haan et al. 2012). However, reliance on market regulation allowed excessive risk-taking in the financial sector and destabilized the global financial system. Recently, scholars and policy-makers have considered the potential of implementing counter-cyclical regulatory measures to make the financial sector more resilient (Griffith-Jones et al. 2009; Independent Commission on Banking 2011). Proponents of counter-cyclical regulation argue that bank supervisors need to take pro-active measures when they observe vulnerabilities in the banking system, especially to cool off credit booms (Grabel 2007; Goodhart and Persaud 2008).

This book investigates the choice of bank supervision approach in four EU member states from Central and Eastern Europe – Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, and Slovenia – after their transition to democracy and market economy. Established shortly after 1989, bank supervision organizations in these countries had to strike a balance between market self-regulation and pro-active regulatory intervention. A handsoff approach emphasizing market-based regulation could attract foreign investors, but it could also fuel credit bubbles that undermine long-term economic stability. A more interventionist supervision approach could curb risky bank-lending practices. Yet, on the flipside, it could also discourage foreign investors and stifle lending. The EU’s new member states from Central and Eastern Europe show different calibrations of the balance between market-based regulation and risk-averse counter-cyclical regulation across countries and over time. This allows us to examine the most important factors that shape a country’s approach to banking supervision.

I argue that the choice of regulatory approach is rooted in domestic politics. To shed light on the selection of banking supervision strategy, I use a most similar systems comparative case-study design focusing on four countries. Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, and Slovenia are most similar systems with respect to their structural position in the global economy. As recent members of the EU, all four countries have been influenced by the common European regulatory framework in banking and finance. At the same time, the four cases display variation in the choice of banking supervision approach as well as domestic factors such as economic reform path, bank privatization and level of foreign ownership, institutional structure of banking supervision, and party politics.

While I focus on the domestic determinants of banking supervision policy, in Chapter 3, I also consider the role of international actors such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the EU, which have undoubtedly influenced the regulatory framework in Central and Eastern Europe since 1989 (Jacoby 2004; Vachudova 2005; Grabbe 2006; Epstein 2008a; Pop-Eleches 2009). The most similar systems research design employed here allows me to investigate why Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, and Slovenia opted for different banking regulatory approaches despite receiving largely the same international policy advice and being subject to the same set of conditionality requirements.

The methodological approach used in this book is an explaining-outcome variant of process tracing (Beach and Pedersen 2013). While the qualitative methods literature has emphasized theory testing process tracing (George and Bennett 2005; Collier 2011), Beach and Pedersen (2013) have put forward another variant – explaining-outcome process tracing (see also Hall 2013). Theory testing process tracing starts out with existing theoretical propositions. The researcher then tests whether the evidence in a single or comparative case study supports or contradicts the hypothesized causal relationships. Theory-building process tracing takes a more inductive approach: the researcher aims to generate new theoretical propositions based on the evidence observed in a single or comparative case study. This approach is particularly relevant for phenomena that cannot be explained well by existing theories. Lastly, explaining-outcome process tracing, which I employ in this book, starts with identifying an outcome that the researcher wants to investigate. The next step is to reconstruct a minimally sufficient explanation of that outcome, based on the existing theoretical literature and any new insights generated by the cases (Beach and Pedersen 2013).

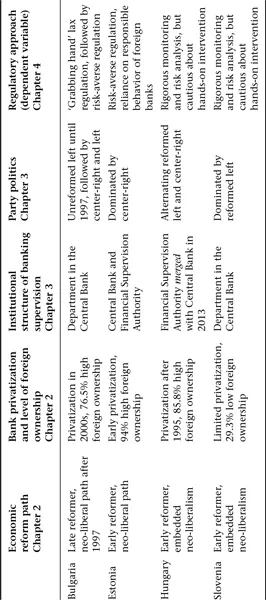

The outcome which I investigate is the adopted banking sector supervisory approach. Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, and Slovenia show different calibrations of the balance between market-based regulation and risk-averse counter-cyclical regulation across countries and over time. Chapters 2 and 3 contextualize in-depth the four independent variables in my analysis: economic reform path, bank privatization and level of foreign ownership, institutional structure of banking supervision, and party politics. In Chapter 4, I examine how the four independent variables shaped the choice of banking sector supervisory approach in each country during the credit booms in Central and Eastern Europe in the early 2000s.

To summarize the structure of this book, Table 1.1 presents the main variables in my analysis. Section 1.2 discusses more in-depth market-based regulation and the micro-prudential supervisory approach. Two international actors have played an important role in the global diffusion of micro-prudential supervision – the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the IMF. Micro-prudential supervisory measures were prominent in the Basel I and II Accords on capital adequacy developed by the BCBS. The IMF has promoted micro-prudential supervision and reliance on Early Warning Systems through initiatives such as the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) and its regular Article IV consultations with member countries.

After the 1998 Asian crisis, scholars pointed out that monitoring risk on the level of individual financial institutions and reducing informational asymmetries were not sufficient to guarantee financial stability (Grabel 2007; Sundaram 2007). Section 1.3 focuses on the development of macro-prudential regulation as a supplement to the micro-prudential approach. Macro-prudential regulation is based on the assumption that increasing banks’ capital buffers is easier in ‘good times’ than in recessions, and bank supervisors should intervene pro-actively to promote greater financial stability (Bini Smaghi 2009; Griffith-Jones et al. 2009; Kowalik 2011; Lim et al. 2011). This section also discusses a range of counter-cyclical regulatory measures that have been put forward in the literature. When it comes to implementing counter-cyclical regulation in practice, Section 1.4 presents the academic debate on using a formula-driven approach versus discretionary instruments and applying harmonized rules across jurisdictions versus national regulatory autonomy.

Table 1.1 Key variables in the analysis

Source: EBRD (2011).

Before we turn to the market-based supervision approach, a few clarifications are in order about the distinction between regulation and supervision, which I use interchangeably in the book, and the distinction between micro- and macro-prudential supervision. In general, banking regulation refers to rule-making and the legal framework designed to govern the financial sector, while supervision refers to the implementation and enforcement of those rules in specific cases and jurisdictions (Masciandaro and Quintyn 2009; Wymeersch et al. 2012). Barth et al. (2006) describe supervision as ‘the monitoring practice that one or more public authorities undertake in order to ensure compliance with the regulatory framework.’ Furthermore, scholars distinguish between micro- and macro-prudential supervisory measures. Masciandaro and Quintyn (2009) have pointed out that micro-prudential supervision focuses on safeguarding financial soundness at the level of individual financial firms. By contrast, macro-prudential supervision is geared toward monitoring threats to financial stability that arise from macro-economic developments, systemic problems in the financial system, or vulnerabilities in interconnected sectors of the economy (see also Kremers et al. 2003; Herring and Carmassi 2008).

The market-based supervision approach which was prevalent before the 2008 global financial crisis emphasized micro-prudential supervision. As the Warwick Commission (2009) report has highlighted, banking sector supervisors focused predominantly on certification, monitoring, and reporting activities such as licensing of financial sector operators; issuing rules on how financial instruments were listed, traded, sold and reported; and formulating guidelines about the value and riskiness of assets on the books of financial institutions. At the international level, the micro-prudential supervisory approach is clearly visible in the Basel I and II Accords on capital adequacy developed by the BCBS. During crises, micro-prudential supervision focuses on individual banks’ responses to exogenous risks, thus somewhat neglecting the build-up of systemic vulnerabilities and the cumulative impact of banks’ behavior on the economy (Jokivuolle et al. 2009; The Warwick Commission 2009; Independent Commission on Banking 2011). To overcome these blindspots of micro-prudential supervision, after the 2008 global financial crisis, scholars and practitioners have emphasized the need for a complementary macro-prudential supervision which aims to ‘force banks to assume they have more risks than they think they do in the boom – by putting aside more capital than they think they need’ (The Warwick Commission 2009: 13).

The argument about which institution should exercise macroprudential regulation is embedded in a larger body of literature on the optimal institutional design of supervisory regimes (Goodhart 1988; Cukierman 1992; Schoenmaker and Oosterloo 2008; de Haan et al. 2012). Masciandaro and Quintyn (2009) have outlined three main types of supervisory architecture: vertical, horizontal, and integrated. First, in the vertical (or silos) model, supervision follows the sectoral division between the banking, securities, and insurance. Each sector is supervised by its own regulatory organization. Second, in the horizontal (or twin peaks) model, the goals of regulation drive the choice of regulatory architecture. Each goal is supervised by a different authority (Taylor 1995). In practice, this leads to setting up two separate organizations: one to carry out micro-prudential supervision and one to oversee the conduct of business (Schoenmaker 2013). Third, in the integrated (or unified) model, a single authority supervises the entire financial system. Based on a sample of 70 countries that implemented financial supervision reforms in the period 1998–2009, Masciandaro and Quintyn (2009) find that 35 percent of the countries in their study use the unified model, 33 percent use the vertical (silos) one, and only 3 percent use the twin-peaks model. Furthermore, combining the features of different models is relatively common – 29 percent of the countries use a hybrid supervisory architecture.

According to Masciandaro and Quitnyn (2009), the vertical supervision architecture is conducive to the most risk-averse type of banking supervision. Most countries in this category use the Central Bank as the sole, or main, bank supervisor. This institutional arrangement is common in countries where the Central Bank has been extensively involved in banking supervision for a longer period of time. In the 1990s and 2000s, scholars focused predominantly on examining the role of Central Banks in setting monetary policy (Franzese 1999; Copelovitch and Singer 2008). As Central Banks gained more responsibilities for macroprudential supervision in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, the debate has shifted to analyzing whether they can combine their monetary policy mandate with an enhanced role in safeguarding financial stability. Scholars have observed a tension in pursuing both functions simultaneously (Eichengreen et al. 2011). All in all, the 2008 financial crisis challenged all supervision architectures and highlighted that institutional design alone is not sufficient to guarantee financial stability (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009). We now turn to examining more closely the market-based approach to banking supervision.

Section 1.2 Market-based regulation: The Basel Accords, the IMF, and micro-prudential supervision

At the international level, the micro-prudential supervisory approach is visible in the Basel I and II Accords on capital adequacy developed by the BCBS. Bank capital is regulated internationally by compelling banks to meet or exceed a minimum capital requirement, specified by a ratio of capital to assets. Adopted in 1988, Basel I introduced risk-based capital requirements. Before the Basel Accords, in the 1980s, capital requirements were based on banks’ total assets (BIS 1998). Since Basel I, the risk profiles of banks’ assets have also been taken into account to determine the appropriate level of capital adequacy. Under Basel I rules, a bank was considered adequately capitalized if its ratio of capital to risk-weighted assets exceeded 8 percent (Blom 2009).

In most countries that incorporated Basel I into national law, domestic banking supervisors could use a set of additional discretionary powers and require banks to hold more than the minimum prescribed capital. For example, domestic bank supervisors could demand an increase in the bank’s capital ratio above the generally prescribed minimum level if they were concerned about greater risk exposure due to a high concentration of loans to a specific sector or a high percentage of loans given in a foreign currency. Before 2008, however, many supervisory organizations refrained from using these powers.

In 2004, the Basel Committee adopted an updated version of the Basel Accords, commonly referred to as Basel II. Central bankers participating in the negotiations assumed that after a decade of rapid financial innovation, banks had developed reliable sophisticated methods of quantifying credit risk. In turn, these could be used to determine more precisely the necessary levels of capital adequacy. The revised Basel II rules for minimum capital requirements allowed large international banks with more complex balance sheets to use their own internal risk assessment models instead of the fixed-risk models of Basel I (BCBS 2008; Blom 2009). The intention was to design capital requirements that were aligned more accurately with the actual riskiness of bank assets. However, critics of this approach have argued that rather than fostering more efficient capital allocation, it allowed large banks to manipulate their risk models and hide large risks off the balance sheet, while technically complying with Basel II (Jarrow 2006; Saurina 2008).

Furthermore, scholars have established that the emphasis on the individual safety and soundness of banks in Basel I and II has amplified business cycles (Blum and Hellwig 1995; Repullo et al. 2010). Capital adequacy regulations affect banks’ ability to lend in a recession. Under Basel I rules, asset risk weights were considered constant over the business cycle. Thus, high losses in asset values during a recession translated directly into a drop of capital adequacy below the minimum required levels. Consequently, banks’ ability to lend was severely impaired. Jokivuolle et al. (2009: 22) have found that Basel II capital requirements were less pro-cyclical than those in Basel I. Their analysis suggests that the Basel II framework could be improved further by increasing the minimum level of capital adequacy and linking it more explicitly to the state of the business cycle. However, other scholars have pointed out that the negative impact of economic downturns on bank lending was exacerbated under Basel II rules, because the risk weights used to calculate capital requirements are based on internal models or external credit agency ratings which tend to be rather volatile (Blum and Hellwig 1995; Repullo et al. 2010). For example, during the recent 2008 financial and economic turmoil, banks refrained from lending in order to repair their balance sheets and comply with international capital adequacy standards. This decision, however, induced a credit crunch and amplified the economic downturn.

In December 2010, the BCBS released the Basel III framework, which introduced new capital, leverage, and liquidity standards to strengthen risk management in the banking sector (BCBS 2011). The new capital standards require banks to hold more high-quality capital against more conservatively calculated risk-weighted assets. In addition, global systemically important financial institutions (G-SIFIs) have to hold an extra 1–2.5 percent of core Tier 1 capital (BCBS 2011). Basel III also introduced two types of capital buffers: a mandatory capital conservation buffer of 2.5 percent and a discretionary counter-cyclical buffer, which allows national regulators to require up to 2.5 percent of capital in addition during periods of high credit growth (BCBS 2011). To give banks time to adjust to changes in the buffer levels, national bank regulators should announce their decision to raise the counter-cyclical capital buffer well in advance. Decisions to decrease the level of the counter-cyclical buffer take effect immediately. To facilitate information provision, the BIS has made a commitment to publish on its website all forthcoming buffer increases as well as current levels of the capital buffer (BCBS 2011).

The new Basel III leverage ratio introduces a non-risk-based measure to supplement the risk-based minimum capital requirements. It is calculated by dividing Tier 1 capital by the bank’s average total consolidated assets. Under Basel III rules, banks should maintain a leverage ratio above 3 percent (BCBS 2013). Moreover, two newly introduced liquidity ratios ensure that banks maintain adequate funding during economic downturns. The liquidity coverage ratio requires banks to hold sufficient high-quality liquid assets to cover their total net cash outflows for 30 days. The net stable funding ratio requires the available amount of stable funding to exceed the required amount of stable funding over one year of extended stress (BCBS 2013). In practice, this ratio sets out a minimum level of stable funding, based on the liquidity characteristics of a bank’s assets and lending activities. The implementation of Basel III started in 2013, but many jurisdictions are only gradually phasing in the new requirements and, according to the timetable released by the BCBS, full compliance is expected by 2019 (BCBS 2013). In the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction

- 1. The Quest for Financial Stability: Determinants of Regulatory Approach in Banking Supervision - Does Counter-Cyclical Regulation Play a Role?

- 2. Economic Reform Path and Bank Privatization

- 3. Institutional Design of Banking Supervision in Central and Eastern Europe and Party Politics

- 4. Banking Supervision Approaches during Credit Booms

- 5. At the EU Negotiating Table: What Role for National Bank Supervisors after EU Accession?

- Conclusion

- Appendix I: List of Personal Interviews

- Bibliography

- Index