- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Global Histories, Imperial Commodities, Local Interactions

About this book

The papers presented in this collection offer a wide range of cases, from Asia, Africa and the Americas, and broadly cover the last two centuries, in which commodities have led to the consolidation of a globalised economy and society – forging this out of distinctive local experiences of cultivation and production, and regional circuits of trade.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Routeing the Commodities of the Empire through Sikkim (1817–1906)

Vibha Arora

They sometimes believe, justly perhaps, that commerce follows the flag, and sometimes the flag follows the commerce; therefore they [Tibetans] think that politics has something to do with trade.1

I begin this chapter by juxtaposing Richard Temple’s comment made in the late 1880s with a question–reply emerging from Tibet:

Why do the British insist on establishing trade-marts? Their goods are coming in from India right up to Lhasa. Whether they have their marts or not things come all the same. The British were merely bent on over-reaching us.2

This reply, given to the Maharaja of Sikkim during discussions over the Younghusband mission of 1904, was by none other than the Thirteenth Dalai Lama himself, and he was not being alarmist. McKay’s comment that the term ‘Trade Agent’ was a convenient fiction owing to the difficult political circumstances encapsulates this candidly. 3Trading in commodities rooted and routed the British Empire, and commercial control over production and exchange of commodities facilitated political expansion globally. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, trade and politics were not inseparable and trading privileges between nations were negotiated by both subtle political diplomacy and aggressive military campaigns.

Marx and Engels wrote in 1848:

[T]he need of a constantly expanding market for its product chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish [connections] everywhere.4

While admitting that the new forces of industrial capitalism required a constantly expanded market, Marx was unable to resolve the problem of capitalist accumulation. Critiquing Marx, at the turn of the twentieth century John A. Hobson and Rudolf Hilferding argued that capitalist accumulation required the expansion of capitalism into non-capitalist areas through imperialism. Such an analysis was then forcibly taken up first by Rosa Luxemburg and then Vladimir Lenin. Their inflection that it is the invasion of pre-capitalist economies that keeps capitalism alive explains the East India Company’s and later the British Raj’s interest in developing Darjeeling and politically controlling Sikkim. Capitalism increased its profits not merely by acquiring new markets for commodities by various means, trading in the commodities of the new territories and investing its surplus in development of new territories but also by the acquisition of its human and natural resources through imperialism.5 Political control of Sikkim facilitated capital accumulation and expansion of capitalism and also funnelled the British imperial engine into the Highlands of Asia.

Trade in tea accounted for the largest share of the Company’s profits in this period after it gradually became a national drink in England. However, the East India Company and later the British Raj faced great difficulties in finding commodities that the Chinese would accept in exchange. The only commodities that the Chinese traders were interested in or were willing to accept in exchange were opium and raw cotton from India. Hence, much of the tea trade required payments to be made in gold bullion – Tibet was seen as a major source of gold.6

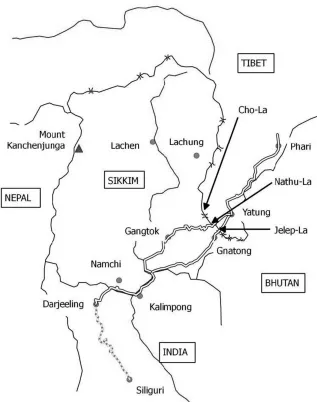

Landlocked Sikkim (see Map 1.1) was never a producer and a great consumer of commodities, but it occupies a strategic geopolitical position on the Indo-Tibetan frontier. It is located directly on the inland trade route between British India and Tibet and China. Diaries of naturalists such as Hooker, travelogues and expeditions to Sikkim and Tibet, the writings of numerous British officers and trade agents posted in the region, and mountaineering expeditions to Mount Everest and other Himalayan mountains including Kanchenjunga were the main sources of information since geographical surveys were conducted after 1861.7

Map 1.1 Sikkim

A socio-historical analysis of international treaties and internal and external trade for the period 1817–1906, and the administration of trade routes, reveals the imperial concern for circulating the commodities of the Empire through the Jelep and the Nathu passes.8 But some key questions are raised: What historic role did the Nathu-la, the annexation of the Darjeeling Hills and the domination of the Sikkim Himalayas play in the expansion and consolidation of the British Empire during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries? What were the main commodities exchanged on this trading route? What was the volume of trade in comparison to Nepal? How did the commodities of the empire provide an impetus and pretext for imperial control of the Eastern Himalayas? This chapter seeks to provide answers to these questions. The first section analyses the importance of Sikkim for furthering Anglo-Tibetan trade and imperial expansion into Tibet in the eighteenth century. The second section traces the historical roots of imperial expansion and control of Sikkim’s internal and external affairs after the Treaty of Titalia (1817) and discusses the formal establishment of the Empire with the annexation of Darjeeling from Sikkim in 1835. The appointment of J. C. White was a turning point as he effectively reduced the king, Thutob Namgyal, into a puppet. The various missions and conventions from 1885 onwards until the Younghusband Mission of 1904 are critically analysed in the third section. I also discuss how these conventions subverted Sikkim’s independence, facilitated trans-border trade and legitimised British Indian claims over Sikkim. The final section highlights the changes in Sikkim’s polity and its incorporation into the British Indian Empire in 1906.

Locating Sikkim in the imperial expansionist policy

British imperial interests in the Himalayan region and particularly in the Eastern Himalayas were motivated by mercantile interests, with the numerous Himalayan passes of Western Tibet (Ladakh), Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan presenting possibilities for using Tibet as the backdoor to China. Trade across the Himalayas and trade between China and Tibet were an expression of both politics and economics, and the Tibetan monasteries were actively involved in this. Trade along these passes was both a commercial activity for numerous Indo-Tibetan groups – such as the Sherpa, Thakali and the Tromwo – and a livelihood necessity, with Tibet being the chief source of salt in the region. Tibet, famed as a land of abundant wealth, presented itself as an exporter of gold dust, borax, musk, wool, salt and sheep (meat) to India and represented a potential market for importing British manufactured textiles, Indian tea, tobacco, grain and mechanistic tools. The gold mines of Tibet were perceived to be the richest in the world, which prompted the British to aggressively promote trade.9

In the 1770s, after the Gorkha conquest of Kathmandu, trade between British India, Tibet and China nearly ceased, and the need for finding an alternate route became urgent. Policymakers realised that improvements in terms of trade would enable the Company to sell British-manufactured goods in China and Tibet, which would reduce the quantity of bullion required to finance tea imports into Britain.10 Risley lucidly commented:

Tibet offers a great market for certain articles of English manufacture . . . and [it was believed that Tibet can] contribute to the currency problem by flooding the world with supplies of gold.11

Both Tibet and China actively resisted British efforts to foster Indo-Tibetan trade. Early attempts to open a trade route to Tibet can be traced back to Governor-General Warren Hasting’s decision to send George Bogle (the young secretary to the Board of Revenue) to Tibet in 1774 to study the markets and resources of Tibet.12 On his return from Tashilhunpo in 1775, Bogle recommended that by befriending the Tashi Lama:

the Company would derive much more than the profits of a flourishing trade across the Himalayas. Tibet was the back door to China and might well prove to be the way round the obstructions imposed upon British trade and diplomacy at Canton.13

In 1783, Warren Hastings sent Captain Samuel Turner on a mission to Tibet, but he failed to secure any trade concessions. To initiate trans-Himalayan trade with Tibet from Bengal through Bhutan, Bogle concluded a treaty with the king of Bhutan in 1775.14 Nonetheless, imperial commercial interests were repeatedly thwarted until they succeeded in controlling Sikkim.

Apart from the famed Nathu-la (Gnatui) and the Jelep-la passes, there exist more than twelve other passes (such as Cho-la, Lachen and Lachung) that connect Sikkim with Tibet, and through whom small-scale trade was regularly conducted. The religious affiliation between the monasteries and the kinship links between the nobility of Sikkim and Tibet presented a perfect corridor for facilitating trade between Bengal and Tibet.

Routeing the empire through Sikkim and the importance of Darjeeling

P. J. Marshall distinguishes between colonial expansion – including migration, commerce and diffusion of British culture – from ‘empire’ – defined as imperial rule and extension of political authority over territory and people. He admits that many would dispute this distinction, and in many cases expansion preceded the empire.15In Sikkim, expansion and empire were interdependent processes and mutually reinforcing. The East India Company functioned not merely as a commercial body but as a potential political power in India. Mercantilism and the desire to maximise revenue through trade via Sikkim surface prominently in all the international treaties and conventions signed between representatives of the British East India Company and later the British Raj, and the Namgyal dynasty that (formally) ruled Sikkim. The British entered the region as peacemakers between Sikkim and Nepal and negotiated the Treaty of Titalia (1817), demarcating Sikkim’s border with Nepal. However, these trade interests were transformed gradually into imperial dominion over independent Sikkim, the annexation of the Darjeeling Hills and the curtailment of Sikkim’s international relations and restrictions on its commercial and political relations with Tibet. Ostensibly to promote Anglo-Tibetan trade and commercial relations, the military campaign under Colonel Younghusband in 1904 proved to be the turning point, with Sikkim playing a key role in it.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Titalia, Sikkim ‘placed its foreign relations under a measure of company rule’ in return for protection from the Gorkhas. Henceforth, the company acquired the right to trade on the Tibetan frontier using the inland route through Sikkim. The British were able to exploit these trade concessions only after 1861 since the Nepal route was an established one. Article 8 of this Treaty explicitly instructs the Sikkim king:

that he will afford protection to the merchants and trader’s from the Company’s province’s and he engages and that no duties shall be levied on the transit of merchandise beyond the established custom at the several golas or marts.16

Politically this treaty transformed Sikkim into becoming a node for channelling Anglo-Chinese diplomacy.17

By the mid-nineteenth century the Indian rupee became an acceptable currency in the Himalayas and emerged as the favoured medium for...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Global Histories, Imperial Commodities, Local Interactions: An Introduction

- 1. Routeing the Commodities of the Empire through Sikkim (1817–1906)

- 2. Indian Pale Ale: An Icon of Empire

- 3. The Control of Port Services by International Companies in the Macaronesian Islands (1850–1914)

- 4. Of Stocks and Barter: John Holt and the Kongo Rubber Trade, 1906–1910

- 5. Coercion and Resistance in the Colonial Market: Cotton in Britain’s African Empire

- 6. A Periodisation of Globalisation According to the Mauritian Integration into the International Sugar Commodity Chain (1825–2005)

- 7. In Cane’s Shadow: Commodity Plantations and the Local Agrarian Economy on Cuba’s Mid-nineteenth-Century Sugar Frontier

- 8. Cuban Popular Resistance to the 1953 London Sugar Agreement

- 9. Tobacco Growers, Resistance and Accommodation to American Domination in Puerto Rico, 1899–1940

- 10. The Battle for Rubber in the Second World War: Cooperation and Resistance

- 11. Beyond ‘Exotic Groceries’: Tapioca/Cassava/Manioc, a Hidden Commodity of Empires and Globalisation

- 12. El Habano: The Global Luxury Smoke

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Global Histories, Imperial Commodities, Local Interactions by Jonathan Curry-Machado in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.