This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The book applies a model of municipal policing to compare a number of police systems in the European Union suggesting that in the future local communities will have some form of police enforcement mechanism that will not always include the sworn police officer.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Municipal Policing in the European Union by D. Donnelly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Preamble

In the twenty-first century, membership of the European Union (EU) is comprised of the following 27 countries – Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Croatia is the latest nation to be accepted into the EU and will become a member on 1 July 2013 which will bring the total number of member states to 28.

The population in the EU as of January 2011 was estimated to be around 502.5 million which is an increase of 1.4 million more than 2010 and continues an uninterrupted pattern of population growth in the 27 EU states since 1960. The figures also equate to 114 people per sq km in one of the most densely populated regions of the world. The EU population has grown by 100 million from its 1960 figure of 402.6 million and according to future EU projections this figure will increase to 525 million in 2035 and peak at 526 million by 2040 (European Commission Eurostat 2011). Just over a third of the increase in population (36.2%) resulted from natural growth (difference between births and deaths), but net migration is the main determinant of population growth in the EU, accounting for 63.8 per cent of the population increase in 2010. The bulk of this population is also free to travel without border controls from the coast of Portugal to the Baltic states and from Greece to Finland. Over 8 million Europeans take advantage of their right to live in another member state and the predictions are that this number will increase in the future. There are 1636 authorised points of entry into the EU and in 2006 the number of people using these means of access were around 900 million, superimposed on these logistics is an estimated figure of 8 million illegal immigrants living at any one time in the EU, most of whom work in the informal black economy (European Commission 2009: 4).

Although illegal immigration remains one of the major challenges facing the EU in the years ahead, organised crime and terrorism also continue to threaten the region’s stability with, for example, 1500 child pornography sites identified on the internet in 2008 and around 600 terrorist attacks either uncovered, foiled or successfully carried out in 2007 (ibid.: 4). Another dilemma facing the EU is the growing resentment and ill feeling between local indigenous people and the rising Muslim population in many member states. It is estimated there are over 13 million Muslims in the EU and the resulting conflicts have moved on from ‘graffiti and no-go zones to arson, assaults and assassinations’ (Judt 2009: 400). The quandary for those in power in the EU is that this increasing minority of unemployed and alienated people are ripe to the attraction of the call of radical Islam. These present and future challenges facing the EU also represent an image of unpredictability in the future development of the EU. Therefore, an understanding of population projections in the EU is essential in any attempt at analysis of the likely impact of demographic change on EU policies in the twenty-first century.

Not surprisingly, projections expect the EU population of working age to decline steadily, while older persons will account for an increase share of the total population. Those aged 65 years or more will account for 29.5 per cent of the EU population by 2060 and the number aged 80 years or more is expected to triple by the same date. Constant low birth rates and higher life expectancy will have a major impact on the ‘age pyramid’ with a significant move towards a much older population and all the difficulties that it brings. Indeed, there are signs of this happening already in a number of EU countries as a greater proportion of the 1960s baby-boom generation reach their retirement. This will leave an ever decreasing proportion of working age people to produce the rising costs of social expenditure necessary to maintain the extensive services required by all sections of society. As the contemporary economist Magnus shrewdly observes, ‘immigration is an important way in which countries with advanced ageing characteristics can supplement future labor or skill shortages’ (Magnus 2009: 8). Social and economic policies are reliant on this kind of data for future planning, and the increasing social expenditure of EU states is closely related to the ageing population with the rising demands of health care, pensions and other burdens, such as community safety and policing issues.

But there is now a will to be European with easy access across the EU and an increasing mix and variety of people, culture and religion. This escalating freedom of movement does bring positive and negative challenges and opportunities to member states in the form of economic, social, law and order, safety and security, crime and community problems, which in turn compels the criminal justice, courts and legal systems to adapt. There are over 420 combinations of language in the 27 member states, English being predominant with German, French, Spanish and Italian close behind. It is also becoming easier to be a European as the transportation and communication is rapidly improving and Europeans know one another better than ever before, now that they can travel and communicate on the same terms. We are all European and there is ‘no way back to the free-standing autonomous nation state, sharing nothing with its neighbour but a common border’ (Judt 2007: 796). The EU is now the largest internal single market in the world and the biggest trader in services exchange employment and movement. It is not a state and does not have its own police service as members remain loyal to their own country and legal system. As in the past, this has always been the role of individual states with citizenry, democratic rights and duty bound up with the state. However, the critical importance of police and security services of the individual states post-‘9/11’ has become glaringly important to EU citizens.

Further to this, member states in the twenty-first century also find themselves facing economic and social challenges from sources beyond their own borders, mainly due to globalisation, as businesses and organisations become worldwide concerns and international mergers are now global. Significant social problems also exist, such as immigration, unemployment, terrorism, political controversy, and religious conflict but a European way of life is emerging with its own model of European society with its single community of over 500 million people.

Reference will be made throughout this book to those EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) which describes former soviet communist states in Europe after the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989–1990, ten of which are now in the EU. The first wave to accede in 2004 were Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, and in 2007 the second wave comprised Bulgaria and Romania. These former soviet socialist countries extend from the border of Germany and south from the Baltic Sea to the border with Greece.

Municipal policing defined

This text deals with what appears to be a recent development called municipal policing, but is a term that has been in the police history books for a number of centuries. The traditional definition of municipal policing incorporated local authority duties, which included crime prevention and patrol by a variety of local enforcement agents, normally employed and controlled by municipal authorities and paid out of public funds, but not always sworn police officers. Depending on the EU country examined these officers have varying powers and duties. Some are restricted to prevention duties and others have enforcement and arrest powers, and in some jurisdictions are authorised to carry firearms. Across the EU these agents have different titles – Communal Police (Romania); Community Security Guard (Austria); City or Village Guard (Slovakia and Poland); Community Support Officer and Community Wardens (UK); City and Village Police (Czech Republic); City Police (Germany); Local Police (Belgium); Provincial or Communal Police and Municipal Police (Italy); Municipal Police (Spain, France, Greece, Estonia and Portugal); Town Watchers (Netherlands) are but a selection.

The all-encompassing police officer of the past is slowly disappearing and issues of visible patrolling, crime prevention and law enforcement are becoming increasingly difficult for the police in face of the ever expanding activities required of them, the growth of the night-time economy, combating anti-social behaviour, the rising fear of crime and demand from communities for reassurance policing are some examples (Crawford 2007). And time and time again the question arises – does the police service have to continue with its full range of functions or is it time to let others get involved and take some of the strain? There has also been an increasing tendency for local authorities to organise themselves to undertake not only regulatory and investigatory duties like health and safety, environmental protection, and trading standards, but certain policing functions with or without police powers. For example, local authorities have formed professional units to combat illegal money lending, unlawful trading, prostitution and drugs, surveillance and CCTV, people trafficking, forced marriages, illegal immigrants, anti-social behaviour, housing and social benefit frauds, counterfeit and black market dealing, environmental offences and many more enforcement appointments. At times police forces have responded to this by entering into partnerships with these authorities and, sometimes beyond that, with the private and voluntary sectors. This new municipal policing approach has been made all the more easier with the advent of new legislation enabling the introduction of auxiliaries and community wardens with a variety of enforcement powers. This has led to the creation of what has become known as ‘the extended police family’ or ‘plural policing’ that in many ways is an extension of what has been in the past. A plural form of policing has always existed, for example, seventeenth and eighteenth-century European history shows that there was always someone who would pay another to perform guarding and prevention duties for them and if you had the misfortune to be a victim of crime then you had no choice but to pursue the offender through a voluntary association at your own expense (Barrie 2008a: 29). The point is that private, local government, local central government agencies and the voluntary sector are taking on an ever increasing role in all areas of policing and this can be given many labels – community policing, municipal policing, neighbourhood policing, third-party policing and plural policing. One could argue that for the sake of clarity the time has now come to drop these descriptors and simply call it policing.

One recent example of a municipal police operation in London saw police officers join forces with Hackney local council to launch an undercover ‘mock fashion business’ in the borough area in order to tackle local gangs. The council-run business enabled undercover officers to gain the trust of some of Hackney’s most violent individuals and obtain key intelligence. The operation culminated in a series of police raids and arrests and convictions of 31 persons for a combined total of 71 years of imprisonment. Local councillor and cabinet member for crime, Sophie Linden, said that the police and council will continue to ‘pursue these criminals using all legal tools available to us’ (Linden 2012). A close examination of police history may also suggest we have gone a full circle and returned to our original starting point, when many police functions were carried out by others in the community, such as park wardens, truancy officers and bus conductors.

A second instance illustrates how local public bodies combat a wide variety of frauds against the public purse, and for the year 2009–2010 English local councils detected around £99 million worth of housing and council benefit fraud amounting to 63,000 fraudulent cases, over £15 million worth of council tax fraud equalling 48,000 cases, and £21 million worth of other types of fraud including false insurance claims and abuse of the disabled parking ‘blue badge’ scheme (Audit Commission 2010a: 12). In addition, nearly 1600 homes have been recovered from unlawful tenants by councils with a replacement cost of approximately £240 million. Not surprisingly, local councils employ a variety of professional fraud and insurance inspectors and in some instances local police forces second police specialists to local council internal audit units to assist with the handling of fraud cases and the subsequent prosecutions (ibid.: 38–39). These new assignments are just further additions to the ever-expanding ‘growth posts’ within the municipal policing model.

A third example highlights the innovative role that can be played by public sector organisations in the continuing conflict against crime. In 2010, an Injury Surveillance Pilot scheme was introduced in the Lanarkshire area of Scotland as a joint initiative between the health board, hospitals, local community safety partnerships and the police and involves hospital staff collecting anonymous information on assaults and violence from persons attending accident and emergency departments. Research has shown that the reporting of violence is under-reported by as much as 50–70 per cent, which tends to suggest that the targeting of police resources is based on a limited amount of intelligence with victims themselves not getting the level of service they deserve (Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) 2011). Such information can include the locations of assaults, times and nature of attacks and weapons used. Experts estimate between 3 and 6 per cent of Scotland’s £10 billion health budget is used to treat victims of violence – if the pilot is successful and subsequently rolled out across the nation many millions of pounds could be saved. A similar project highlighting partnerships at the municipal level relates to dentists being trained to encourage victims of ‘domestic abuse’ incidents to report the matter to the police or support services. The scheme will see dentists trained to spot the signs of domestic abuse as explained by its founder Dr Christine Goodall, ‘victims of domestic abuse often suffer injuries to their teeth, face and neck, so dentists are usually the first healthcare professionals they will see and we felt it was time to take advantage of this “golden moment” to intervene and help’ (VRU 2011).

As we see from above, modern day municipal policing encapsulates partnership working and this is aptly shown in a recent joint initiative in Scotland. In April 2012, the Highland local council’s out-of-hour’s calls for emergencies relating to council housing repairs, property and homelessness, as well as roads, street lighting and environmental services was taken over by the area police force of the Northern Constabulary working in partnership with the local council. Calls between 1700 and 0900 hours will be dealt with by specialist police staff in the force operational centre. The anticipated benefits with this initiative will be making use of highly trained staff and enabling faster and improved coordination should a multi-agency response be required (Highland Council 2012).

As evidenced above, police functions and responsibilities are changing and it is highly likely that public expectations will be increasingly met by non-police officers and new technological systems. The UK has led the field in this form of policing and the comparisons made in this text investigate, where possible, similar trends in European police work, entrusted to local auxiliaries, civilian support officers, public and private sector, voluntary groups, and to the expansion of other forms of administrative justice, such as fixed penalty offences. One senior police officer in England raised some controversy when he stated that ‘low-level anti-social behaviour is mainly the responsibility of the council’.1 His comments were specifically related to dealing with juveniles where there tends to be a sliding scale of how minor offences are dealt with from warnings and reprimands to ‘final warning’ and then a criminal charge. The rationale behind this approach is to prevent juveniles from being ‘criminalised’ in their early years.

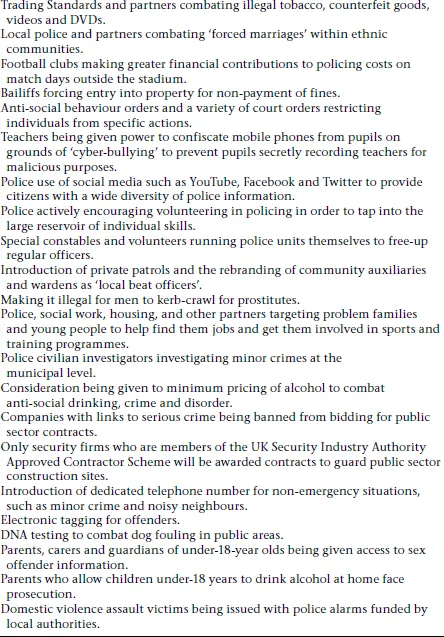

The following is a selection of examples of contemporary municipal policing (Table 1.1) that reinforces the argument that modern police enforcement and prevention initiatives are materialising into a complex patchwork of functions with many actors at play under the labels of third-party policing, community policing, municipal policing, plural policing, private policing, local authorities, government agencies, and the voluntary sector. Most of which are directly or indirectly municipally funded.

Table 1.1 Examples of contemporary municipal policing

Research methods

The resurgence in the idea of municipal policing is accompanied by the expanding partnerships of police forces, local councils, and private and voluntary sector organisations. The purpose of these partnerships has in the past been concerned primarily with reducing the fear of crime, reassuring the public and improving community well-being. Supported by research within Scotland and the wider UK, a ‘loose model’ of municipal policing comprising a set of themes has been devised. The model has seven component elements and its purpose is to facilitate the examination of municipal policing systems in a number of EU member countries.

In the book Municipal Policing in Scotland, Donnelly (2008a) describes the components of modern municipal policing and though not an exhaustive list they comprise:

•History, tradition and partnership

•Municipal policing

•Community policing and communities

•Civilianisation, private security and auxiliaries

•Surveillance and technology

•Governance and accountability

•Politics and policing

This book examines these topics within the context of policing in the EU and the reader can make comparisons between past and present police systems, particularly, local municipal policing. There are limitations to the present research due to the size and disparity of the topics under scrutiny in the 27 EU countries and the time period available. Other challenges in comparative work are also present in the form of constraints on knowledge and information, limited primary and secondary research, language barriers, and having to cope with wide varieties of police systems and cultures. The text is there...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 A Brief History

- 3 Municipal Policing in the EU

- 4 Community Policing in the EU

- 5 Civilianisation, Private Security and Auxiliaries in the EU

- 6 Surveillance in the EU

- 7 Police Governance in the EU

- 8 Police and Politics in the EU

- 9 Future of Municipal Policing in the EU

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index