eBook - ePub

Ways of Regulating Drugs in the 19th and 20th Centuries

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ways of Regulating Drugs in the 19th and 20th Centuries

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This collection takes the perspective that the historiography of science, technology, and medicine needs a broader approach toward regulation. The authors explore the distinct social worlds involved in regulation, the forms of evidence and expertise mobilized, and means of intervention chosen to tame drugs in factories, consulting rooms and courts.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ways of Regulating Drugs in the 19th and 20th Centuries by Kenneth A. Loparo, V. Hess, Kenneth A. Loparo,V. Hess, Jean-Paul Gaudillière, V. Hess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Secrets, Bureaucracy, and the Public: Drug Regulation in Early 19th-Century Prussia

Volker Hess

Introduction

Drug regulation is usually regarded as an outcome of contemporary history closely connected to the rise of a large pharmaceutical industry, the growing drug market, and the expansion of state authority (Chauveau, 1999; Daemmrich, 2004; Bonah and Menut, 2004; Löwy and Gaudilliere, 2006). It may then seem strange to start a special volume on drug regulation with an analysis of drug approval starting in the early nineteenth century. Indeed, there are many differences between today’s regulation and the kind of regulation presented here. Neither the aims, nor the tools, nor the objects seem to be comparable with our current concept of drug surveillance (Abraham and Reed, 2002; Abraham and Davis, 2006). Today, the drug market is dominated by ready-made specialties portioned in galenic preparations. The active ingredient is mostly comprised of a single chemical or biological substance, and more rarely two or three substances. The effects are usually explained in physiological terms (aside from psychological effects, as with a placebo). Regulation is therefore about maximizing effectiveness, reducing toxicity, and avoiding adverse reactions, and involves state authorities, as well as professional groups (physicians and pharmacists), companies, and NGOs (grassroots, self-help, consumer-support and advocacy organizations, patients, and families).

In contrast, in the late modern period, drugs were usually mixtures of different components of herbal or animal origin. They could only be obtained in drugstores and delivered personally by trained pharmacists. The corporately organized profession ensured availability, freshness, purity, and fair trade in drugs on behalf of the state authority, though subjected to its supervision. Regulation served not only to protect people from quacks, overpriced drugs, and ineffective remedies, but also to maintain pharmacists’ traditional privileges (Huhle-Kreutzer, 1989). As such, regulation was an integral part of the give and take of corporate rights and duties.

A closer look, however, reveals some analogies between late-modern and current ways of regulating. One class of drugs in particular, the so-called secret remedies, were tested and approved in a way that shows similarities with modern practices. First, secret remedies were treated as a drug product. Often produced in proto-industrial ways, secret remedies rather anticipated the later development of large-scale production (Huhle-Kreutzer, 1989). Like current drugs, secret remedies were also aggressively marketed in newspapers and broadsheets (Ernst, 1975). We should therefore not believe the enlightened choruses of philosophers, physicians, and officers condemning secret remedies for their secret and mystical aura. Second, secret remedies were considered intellectual property. In contrast to contemporary officinal drugs, their formulas were not listed in the materia medica. Like recent drugs, their compositions remained secret – and the state authorities acknowledged the status of intellectual property (for the German case, see Wimmer, 1994; for the French side, Chauveau, 1999). Third, secret remedies were subjected to administrative regulation. They became the object of an official approval procedure, in which they were tested for their active ingredients, harmlessness, and effectiveness (Kibleur, 1999; Thoms, 2005). Fourth, already then, the public and publicity played a crucial role. Like contemporary drug products, secret remedies depended necessarily on publicity: producers sought public attention for their marketing and tried to generate among the public assurance on the potency and virtues of the drug being supplied. In fact, the public sphere made the difference between a secret remedy and an unknown product. As a consequence, the status of a secret remedy was in fact constituted by the public. Secret remedies might then differ from recent pharmaceutical products as to their ingredients and composition, but on the medical market, they were more similar to current drugs than the official materia medica. In short, secret remedies can be considered as the legitimate precursor of industrially manufactured products. This also shows the regulation process as precursor of modern state regulation.

There are consequently reasons for using the heuristic model outlined in the introduction (Table 0.1). Distinguishing the different ways of regulating drugs in the late-modern drug market will trace back contemporary configurations to their beginnings, which may help to understand the main separations made between the state, science, and the Öffentlichkeit (public sphere). The German term encompasses more meanings than the English one. It includes the idea of the spatial representation of an enlightened and universal rationality shared by “all men free to use their own reason.” This Habermasian public sphere might be a phantasm, but it drove action – as its imagined counterpart – when philosophers, physicians, and officials made decisions with respect to the Öffentlichkeit (Mah, 2000). This perspective from the origins will also help to characterize the contemporary situation of different aims, actors, procedures of evidence, and regulatory tools. To demonstrate this, I will use the figure presenting the ways of regulating (Table 0.1) to evaluate the Prussian procedure of approving secrets remedies. First, I will consider the industrial way of regulating, in which manufacturers, producers, and traders of secret remedies were involved. The following section will discuss the role of the public sphere, in which consumers make public opinion. Finally, I will analyze in greater detail the reorganization of the approval process in the 1830s, in which scientific expertise was mobilized to justify state concessions. Concessions for secret remedies were increasingly granted on the basis of scientific objectivation as a result of pharmaceutical analyses and clinical trials. These brought experts into play, and their role became critical by intermixing public reason with the state’s interest.1 Societies in the process of industrialization found different models for stabilizing, insulating, and protecting scientific expertise. In Prussia, experts challenged the presumed neutrality and impartiality of the state’s authority. As a consequence, drug regulation was organized as a bureaucratic routine that tried simultaneously to integrate and to separate the elements of both an administrative and a professional way of regulating. Developments in France will serve as a counterpart: here, the administrative and professional powers were separated in a different way, which was intended to ensure the impartiality of science.

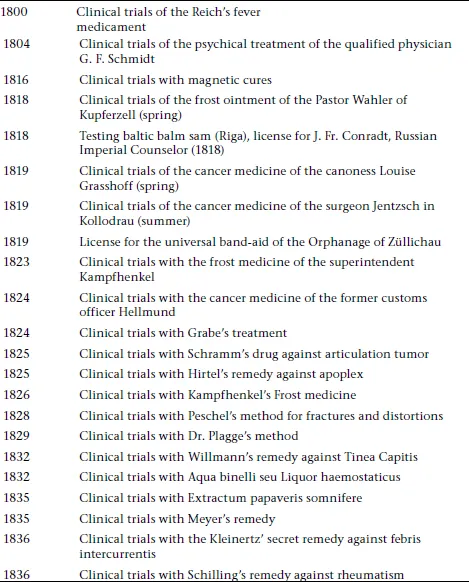

My argument is based on the archival records of more than 270 applications submitted between 1800 and 1865 (Hess et al., 2006).2 Many of them resulted in chemical and pharmaceutical analyses, and a few involved clinical trials. The files all contain the owner’s application, and many of them contain patients’ submissions and recommendations, and the related correspondence with and among the authorities.

Producers

In the late modern period, secret remedies were widespread and often banned by the medical authorities. Unlike other European states, Prussia had never forbidden them. Instead, the medical laws of 1693 and 1725 (as cited in Stürzbecher, 1966: 27–34) made their production and sale conditional to official authorization. We do not know how this authorization was obtained in Prussia prior to the early nineteenth century, but from then on, archival records reveal how the medical authorities organized the approval process.3 An administrative file was set up for each application to sell a drug or to purchase a secret formula. The range of submissions was broad (see Table 1.1), extending from psychological procedures to cure mental diseases to aggressive chemicals for treating cancerous ulcers. Many cases fell into the category of household remedies and traditional medicine, such as Baltic Balsam or various anticold medicines. Only rarely do we find new treatment methods in submissions to medical authorities. The spectrum of the secret-drug owners was also wide: there were medical professionals, especially from the lower ranks, but also laymen, such as chandlers and merchants, retired civil servants, and clergy, all of whom wished to profit from their secret knowledge.

One may ask what requests for licensing homespun remedies or medical inventions has to do with the commercial manufacturing and sale of drugs. As the files show, however, most applications aimed not at initiating a commercial activity, but at legalizing an existing one. Applicants had not been passively sitting on their secret or waiting for a state license. On the contrary, some even asked for an official authorization by attaching printed leaflets and advertisements for their fabulous remedies.4 Other applicants praised their remedies based on many years of successful therapeutic use. In other cases, official requests for approval were combined with pleas to license unqualified medical activities in the face of pending punishment.5 In short, as commercial products, secret remedies shared the economic rationale that has been well analyzed for the French case (Brockliss and Jones, 1997: 238–45 and 628–30; Ramsey, 1982: 218). The mass of files (and applications) indicates an intensification of traditional commerce in Prussia. Particularly around the 1850s, there were more remedies being produced and sold in a proto-industrial way. One applicant remarked that he had already incurred the cost of several hundred dollars to purchase flasks. For this reason, the applicant, a privy councilor named Meyer, argued that if the ministry did not allow the manufacturing of his new cholera remedy, his very existence was threatened by economic loss.6 Another applicant justified his request by claiming that he had set up repositories in the whole country: although he already had a concession for his eye water, he argued for a renewal so he could fill contracts to produce thousands of flacons for drugstores. He also argued that the ministry would be responsible for his bankruptcy if the application was not given approval.7 This marketing technique suggests a professional manufacturing system and a professional distribution system – both of them characteristic of a growing proto-industrial organization starting in the 1850s.

From this perspective, we can explore the producer’s way of regulating this kind of medicine. We did not find any indication that the production processes were regulated. Distribution was made official with restrictions to a specific region. In practice, however, the long arm of the Berlin authorities did not reach the local authorities to enforce such restrictions.8 Once granted, the license opened the door to the market, in which producers would then distribute their products liberally. Thus, the crucial point in the game was the application procedure, which producers tried to influence and organize. Compared with the scientific methods that we have today for objectifying effectiveness and harmlessness, their tools seemed limited. Indeed, neither of these two modern criteria was used in application documents. Instead, we find two very common and constantly recurring arguments. First, applicants stressed the unique and exceptional character of their product. A secret formula was authoritative experience being passed down from generation to generation. A second argument was that the remedy was the fruit of a long and successful practice to which the applicants laid claim despite their lay status. Documents accompanying the application (such as letters of recommendation) attested to how perfectly well the remedy worked, to a group of patients who tolerated it, and to unanticipated therapeutic benefits.9 Flyers and other advertisements demonstrated the successful use of the remedy, no matter that they were also proof of illicit activities and commercial interests, which applicants did little to hide.

Table 1.1 Secret remedies applied for approval in Prussia, 1800–40 (selection)

The second argument is more interesting in the sense that the applicants claimed moral qualities for themselves. If we believe them, financial rewards never motivated their application. The only reason stated for making long-kept secrets public was disinterestedness and duty to humanity (Hess, 2006). Alternatively, the “welfare of mankind” or “the suffering” and “needs of the whole of mankind” drove applicants to disclose their property.10 Sometimes, such claims prompted sarcastic observations from ministerial officials, confident that rejecting the application would not harm the well-being of humanity.11 Nevertheless, remuneration was sought as compensation through the promulgation of intellectual property. The amount was not set according to the promised benefit of the remedy but as a factor of personal living conditions: to ensure a living wage, to help in a situation of dire financial straits, or to be able to support old and feeble parents. Thus, one applicant wanted “to secure a partial livelihood for herself and her daughter by marketing the tincture that [she] enclose[d] as a sealed sample.”12 A second applicant hoped to improve her retirement pension by revealing her cancer medicine, and a third requested 600 Reichsthaler for his impoverished father.13,14 The wordy illustrations of bad conditions and daily troubles did not call on the state’s duties to relieve poverty; they were meant to demonstrate the applicants’ personal integrity. Every effort was made to ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- General Introduction

- 1 Secrets, Bureaucracy, and the Public: Drug Regulation in Early 19th-Century Prussia

- 2 Making Salvarsan: Experimental Therapy and the Development and Marketing of Salvarsan at the Crossroads of Science, Clinical Medicine, Industry, and Public Health

- 3 Professional and Industrial Drug Regulation in France and Germany: The Trajectories of Plant Extracts

- 4 Making Risks Visible: The Science, Politics, and Regulation of Adverse Drug Reactions

- 5 Regulating Drugs, Regulating Diseases: Consumerism and the US Tolbutamide Controversy

- 6 Thalidomide, Drug Safety Regulation, and the British Pharmaceutical Industry: The Case of Imperial Chemical Industries

- 7 Whats in a Pill? On the Informational Enrichment of Anti-Cancer Drugs

- 8 Treating Health Risks or Putting Healthy Women at Risk: Controversies around Chemoprevention of Breast Cancer

- 9 AZT and Drug Regulatory Reform in the Late 20th-Century US

- 10 Professional, Industrial, and Juridical Regulation of Drugs: The 1953 Stalinon Case and Pharmaceutical Reform in Postwar France

- 11 Managing Double Binds in the Pharmaceutical Prescription Market: The Case of Halcion

- 12 Pharmaceutical Patent Law In-the-Making: Opposition and Legal Action by States, Citizens, and Generics Laboratories in Brazil and India

- Index