This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Featuring sixteen contributions from recognized authorities in their respective fields, this superb new mapping of women's writing ranges from feminine middlebrow novels to Virginia Woolf's modernist aesthetics, from women's literary journalism to crime fiction, and from West End drama to the literature of Scotland, Ireland and Wales.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The History of British Women's Writing, 1920-1945 by M. Joannou, M. Joannou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Mapping Modernism

1

Gender in Modernism

Bonnie Kime Scott

Coping with gender was an enormous challenge for women writers of the modernist era, on personal, professional, geographical, and theoretical grounds. In her first novel, The Voyage Out,1 Virginia Woolf enlists a young male character, Terence Hewet, to express scepticism about any rapid alteration of gender norms in the early twentieth century. Hewet considers ‘the masculine conception of life’ to be ‘an amazing concoction’.2 He speaks to Rachel Vinrace, a gifted young pianist belatedly coming into political and self-awareness while visiting an Amazonian location in coastal South America:

‘It’ll take at least six generations before you’re sufficiently thick-skinned to go into law courts and business offices. Consider what a bully the ordinary man is,’ he continued, ‘the ordinary hard-working, rather ambitious solicitor or man of business with a family to bring up and a certain position to maintain. And then, of course the daughters have to give way to the sons; the sons have to be educated; they have to bully and shove for their wives and families, and so it all comes over again. And meanwhile there are the women in the background … Do you really think that the vote will do you any good?’3

Being more concerned with musical goals, Rachel is indifferent to the vote. While the exotic location of the novel might be expected to produce some distance from British gender norms, Rachel and Terence still struggle with custom as they become involved in their own marriage plot. The novel also demonstrates ways in which gender intersects with other social categories, including sexuality and national and imperial attitudes, and it records nightmares and post-impressionist landscapes that usher in Woolf’s modernist experimentation. In ultimately denying the marriage plot, Woolf launched herself into a career that would trouble the complex politics of gender in Modernism and modernity. She had a great deal of company, both in Britain and in the wider world of Modernism.

Masculine modernist formulations

Modernism, as an experimental endeavour that aimed at revolutionizing literature in the early decades of the twentieth century, came to be known in decidedly masculine terms, as I first argued in the introduction to The Gender of Modernism in 1990.4 Among the formulators working in London were T.E. Hulme, with his preference for Classicism over Romanticism, Wyndham Lewis, in his influential periodical BLAST (published 1914–15) and in his book Men Without Art, Ezra Pound, as a definer of ‘imagism’ and ‘vorticism’ and as an ambitious editor, and T.S. Eliot, in ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, among his many influential critical pieces. Their views on the forms that writers could employ to engineer literature – to ‘make it new’ (Pound’s phrase, used in 1934 as a title for a collection of his essays) – continued to be privileged well into the 1980s. This privileging began with the New Critics, who helped set academic canons of the 1950s, continued with the influence of Hugh Kenner, and persisted in the early work of Michael Levenson.5 Kenner coined the phrase ‘The Pound Era’, using it as the title of one of his most influential books, and spent considerable energy discrediting Woolf and Bloomsbury.6 Pound and Eliot have remained central figures in the journal Modernism/modernity (founded 1994), despite its inclusion of new Modernisms and its insistence upon the broader category of modernity alongside Modernism.

Masculine metaphors of Modernism included ‘dry hardness’, which Hulme attributed to Classicism, as opposed to attitudes of flight, ‘sloppiness’, or ‘moaning and whining’, which he attributes to the Romantics.7 Pound was fond of genital figurations, even for the brain. In these, active ‘making’ relied on the male organ. In his postscript to Remy de Gourmont’s The Natural Philosophy of Love, Pound reports having felt as if ‘driving any new idea into the great passive vulva of London, a sensation analogous to the male feeling in copulation’.8 In both this work and in correspondence with American poet and editor, Marianne Moore, Pound associated women with ‘chaos’, though he also called attention to H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), another American, then working in England, as an exemplary poet of imagism. When Amy Lowell arrived in London from the United States and began to challenge Pound with her own ideas of imagism, demonstrating that she possessed both the energy and the necessary private resources to produce her own anthologies, Pound turned his attention to the supposedly more dynamic form of vorticism. Wyndham Lewis repeatedly blasted feminine form and sentimentalism, often blending his ‘blasts’ with homophobic attitudes toward practitioners of decadence and aestheticism. Despite its association with the natural substance of water, Lewis’s idea of ‘vorticism’ is a technical concept, the vortex being geometrically shaped, pointed, and energetic, having ‘polished sides’ and making swift, repeated, penetrating motions.9 Practitioners of vorticism such as Nietzsche’s superman are ‘masters’.10 To Lewis, Virginia Woolf represented an introverted figure brooding over a subterraneous ‘stream of consciousness’, which is ‘a feminine phenomenon after all’.11 Eliot offered his own examples of the need for classical and technical control in the creation of art, figured scientifically with his celebrated catalyst, a shred of platinum, which he invokes to represent the mind of the poet.12

Since the late 1960s, feminist scholars have done a great deal of work of recovery and revision, not just in identifying the neglected women of Modernism, but also in engaging a wider set of genres and audiences for Modernism as a manifestation of modernity and bringing into the discussion work that was going on outside the urban, cosmopolitan, technological centres of Europe and the United States. Indeed the revision of Modernism has taken place on numerous fronts, including postcolonial and queer Modernisms, and in more elastic groupings, such as the ‘intermodern’, a classification challenging periodization as well as modernist formal constraints and audiences. Modernism, as codified by the group Lewis defined as the ‘men of 1914’, was shaped in reaction to numerous cultural forces and further challenged by them as the twentieth century progressed. These included suffragists’ endeavours to secure votes for women (only partially satisfied in 1918 in the UK), resistance to forms of popular culture widely dispersed in increasingly globalized cultures of modernity, and the emasculating effects of the First World War. That war brought not only the sacrifice of a generation of promising young men (including Hulme and de Gourmont) but also the gradual acknowledgement of shell-shock as a widespread phenomenon, comparable to forms of hysteria long associated with the female sex. Fought on a world stage, with women assuming new roles in the public sphere, and many of the players originating in the colonies, its later expression in modernist texts brought both greater diversity and awareness of a changing world order and provoked a crisis in masculinity.

Female networks for Modernism

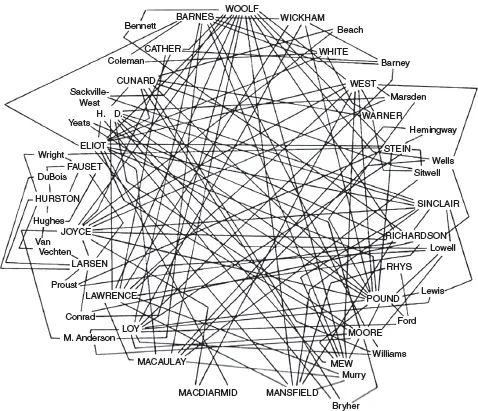

As feminist recovery work has revealed, women were important not just in providing networks and venues for male formulators of Modernism but also for offering critiques that would shape its range and direction. Modernist women assumed active roles as editors or de facto editors of modernist little magazines, and wider circulation in more varied journals, as reviewers and essayists, and in publishing. Many of these relations were sketched out in the introduction to The Gender of Modernism, and included here is a figure from that text, representing the complex set of relations that worked intricately across sexes, sexualities, and even race (Figure 1.1). It is based on actual connections made by contributing editors to that text; others certainly existed.

Figure 1.1 A tangled mesh of modernists

Source: Bonnie Kime Scott, The Gender of Modernism: A Critical Anthology (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), p. 10.

Sitting at the top of this ‘mesh of modernists’, Woolf has one of the richest arrays of connections, some forged by her published essays and extensive reviewing of contemporary writers, some through the publications of the Hogarth Press, which she and Leonard Woolf established with a small hand press in their home in 1917. Among its early publications were innovative modernist texts, including Woolf’s Kew Gardens, Katherine Mansfield’s The Prelude, and Hope Mirrlees’s Paris, which in many ways anticipated another of its notable publications, T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Woolf’s interest in psychology and in Russian contributions to Modernism later found expression in the Hogarth list, as they did in her important essay, ‘Modern Fiction’. Hogarth Press’s early covers and illustrations, and its series dedicated to essays and letters further diversified Modernism.13 British-born Nancy Cunard commands attention for her Hours Press and for editing the anthology Negro, published in Paris in 1934. This massive volume had regional sections on America, the West Indies and South America, Europe, and Africa, achieving global range. Samuel Beckett served as a translator, and canonized modernists were scattered among predominant contributions by American blacks, including key writings by Zora Neale Hurston, as well as work by Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, and W.E.B. Du Bois. Similar efforts existed in other global locations such as Argentina where Victoria Ocampo operated Sur Press.

The number of connections generated by the British novelist May Sinclair may seem surprising, but it is indicative of her energetic work both outside and inside modernist circles in the making; many of these connections are with other women who have also remained relatively obscure. Sinclair was one of numerous well-connected women who helped Ezra Pound establish himself among modernists when he arrived in London from the United States in 1908. She provided key introductions to Violet Hunt and her partner at the time, Ford Madox Ford. Another important engineer of connections, Hunt gathered the younger writers at South Lodge – a group that included D.H. Lawrence, H.D., her British husband, Richard Aldington, Wyndham Lewis, G.B. Stern, and Rebecca West. Through Ford, Pound gained access to The English Review, where Sinclair made numerous contributions to the conceptualization of Modernism. Indeed Sinclair was an important promoter of modernist women writers, including H.D., who formed her own strong intellectual and personal alliances with British writers, including Aldington, Lawrence, and Bryher (Winifred Ellerman). A reader of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on the Contributors

- Chronology 1920–1945

- Introduction: Modernism, Modernity, and the Middlebrow in Context

- Part I Mapping Modernism

- Part II Cultural Hierarchy

- Part III Gendered Genres

- Part IV The Mobile Woman

- Electronic Resources

- Select Bibliography

- Index