eBook - ePub

Policy-Driven Democratization

Geometrical Perspectives on Transparency, Accountability, and Corruption

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Policy-Driven Democratization

Geometrical Perspectives on Transparency, Accountability, and Corruption

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Policy-Driven Democratization offers a comprehensive conceptual analysis of each one of these fuzzy terms separately to then sew them together in one complete and coherent package of democratization.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Policy-Driven Democratization by Peride K. Blind in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Relaciones internacionales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE CONCENTRIC CIRCLES OF DEMOCRATIZATION: TEASING OUT THE COMMON DRIVERS

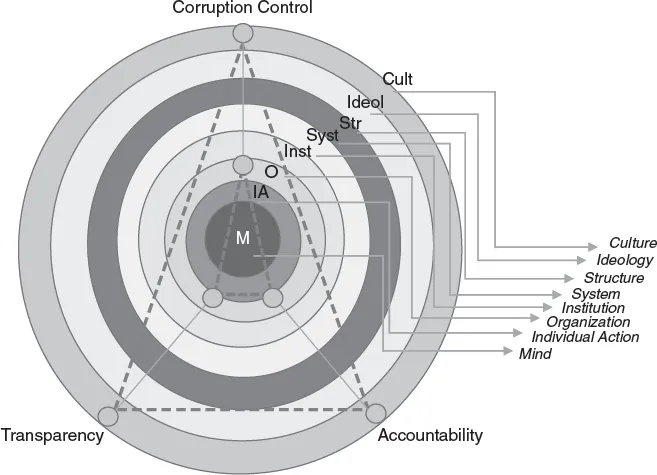

The Stoic philosophers of the fourth century BC believed in the idea of oikeiosis. Oikeiosis proposed to gradually expand one’s closest attachments to oneself on to the family, society and eventually all of humanity. The early Stoic philosopher Hierocles depicted the idea of oikeiosis through his concentric circles of identity: the innermost circle represented the individual; the surrounding circles stood for immediate family, extended family, local group, citizens, countrymen and humanity, in this order. The objective of oikeiosis was to draw in people from the outer circles into the inner ones, based on the assumption that all human beings belong to one single and universal community with a shared morality at the core. As such, oikeiosis became the basis of cosmopolitan ethics.1

The definitions and the various understandings of democratization since the 1950s can be likened to Hierocles’ concentric circles. The search to define and understand democratization shows an overall tendency to move from the outer layers to the inner layers of the concentric circles of democratization. Democratization, which sprang as a corollary of overall socioeconomic development, moved from the outmost circles of cultural and structural change to systemic and institutional reorganization, and from there to individual elite interactions, and their dealings with mass society representatives, and from there back to mid-level circles of state–society dealings and community-led projects of sociopolitical liberalization.

The move through the concentric circles has neither been constantly unidirectional from the outer to the inner layers nor has one circular layer been the only level of study of democratization at any given point in time. Often, fragments from different layers of analysis have coexisted, one layer dominating rather than excluding others at any given time. The individual-level understandings of democratic transitions in the 1980s, and the following institutional analyses of democratic consolidation in the 1990s, for instance, have culminated in the eclectic democratization studies, including historical, structural, cultural and agency-based explanations in the 2000s.

The increasingly eclectic definitions of democratization conform to the oikeiosis idea of democratization. The rising appreciation of the multifaceted nature of democratization implies that teasing out the common ingredients across all circles, rather than trying to prove the most adequate circle(s) of democratization, could benefit the democratization literature and policy making. If delineated properly, these common elements could be the drivers of democratization rather than its immediate or deep-rooted causes, yet still exert significant impact on the processes and outcomes of democratization. Such an exercise, reminiscent of the System II Model by Kahneman (2013), could take us closer to a more consensual and applied understanding of democratization.

The model of concentric circles of democratization is an exercise in approaching politics of democratization to its policies, thereby contributing to a more policy-driven understanding, and hence a more effective implementation of democratization. Preliminary research shows that open communication and free flow of information, answerability to citizens and accountability, and corruption control are essential ingredients of democracies. Yet, they are seldom studied systematically in a comprehensive work whereby they are interlinked with each other and with democratization. This book proposes to focus on these three common drivers across all circles of democratization to offer an oikeiosis definition of democratization.

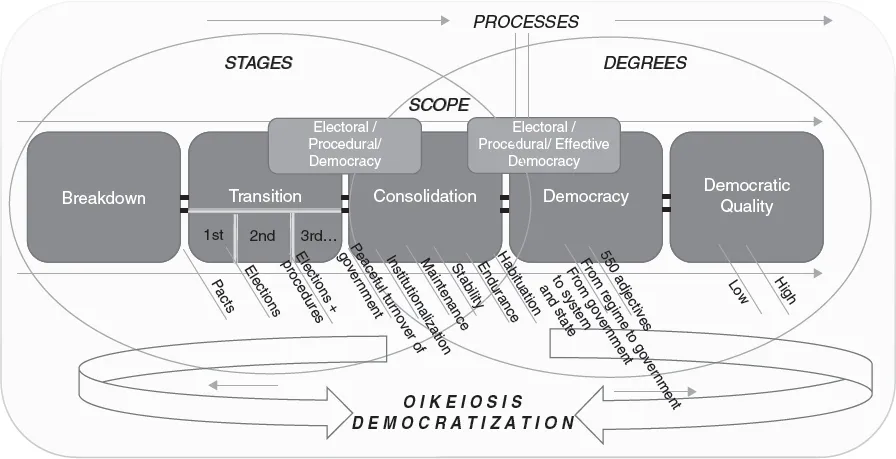

THE IDEA: OIKEIOSIS OF DEMOCRATIZATION

An oikeiosis understanding of democratization implies adopting a holistic view on the processes of attaining, maintaining and developing democracies. Despite its inherent complexities, this book adopts the Occam’s Razor principle to define democratization simply as moving from a lack or low level of democracy to a beginning or higher level of democracy. Democratization, for our purposes, is thus the establishment and the upgrading of democracies. Such a definition consciously repudiates the segmented view that has dominated the literature. As shown in Figure 1.1, the segmented view of democratization includes mainly four conceptual categories: (i) process-led differences or the democratization versus democracy debate; (ii) scope-led differences or the procedures versus rights debate; (iii) stage-led differences or the transition versus consolidation debate; and (iv) degree-led differences or democracy versus democratic quality debate.

Regarding process-led differences, there is a tendency in the literature to associate democratization with the origins of a specific regime type, and democracy with the stability of this regime. While such theoretical distinctions and arbitrary thresholds are useful for didactic purposes, they are not empirically verifiable. This study assumes that disassociating the later phases of democracy from the overall process of democratization is unproductive, at the very least because the process has no end point to it. Ideally, a democracy, or polyarchy, depending on the extent to which one deems full democracy to be attainable, should be continuously democratizing regardless of whether it is a new or established democracy. This study, therefore, does not separate the origins of a democracy from its stability. It assumes that democratization is a continuous endeavor, and not only restricted to newly emerging democracies.

Regarding scope-led differences, there is voluminous research on whether democratization should include political rights in addition to fair, free, regular and competitive elections, and whether political rights should be accompanied with social and/or economic rights for full(er) democratization. This study adopts a holistic rights-based approach to view democratization as expanding social and economic rights in addition to political and human rights. Neither elections nor the number of turnover of governments, distribution of land or income equality are by themselves sufficient to make democratization a success. Procedures are crucial but are not sufficient by themselves to offer a complete understanding. Democracy as such is not simply about the choice of procedures that regulate access to state power (Mazzuca 2007) or the effectiveness of the executive to rule (Collier and Levitsky 1996). It is instead a situation of human dignity and political equality ensured by socioeconomic forces, including issues pertaining to distributional conflicts and resource endowments (Acemoglu and Robinson 2006, Vanhanen 2007).

Figure 1.1 Segmented versus Oikeiosis Democratization

Regarding stage-led differences, most studies are prone to impose temporal frontiers to democratization. For instance, there is significant consensus in the literature that the beginnings of a democracy, or democratic transitions, have different causes and consequences than its later stages referred to as democratic consolidation (Shin 1994: 151). The theoretically useful distinction between transition and consolidation has monopolized the democratization debate to the extent that the real endeavor to understand democratization for what it really is has been lost. It might thus be more beneficial to devote time and energy to see the actual policies that have fostered and advanced democratization throughout rather than figuring out where to draw the line between the breakdown of autocracies, the start and end points of democratic transitions, when democratic consolidation starts and ends, and whether it can be equated with democratic stability, maintenance, persistence, endurance or habituation.2

Regarding degree-led differences, there have been distinctions in the literature drawn between democracies, and democracies with low and high qualities. Many scholars have differentiated between democratic consolidation and democratic quality by associating the former with temporal stability and the latter with regime characteristics such as corruption, weak rule of law, class and other types of persistent or intermittent conflict. The same scholars, though, have also tended to use the two concepts interchangeably. Furthermore, such characteristics associated with democratic quality, particularly corruption and the weak rule of law, have been cited extensively as the main reasons for failures of democratization, by the same and other scholars. This study does not view the adjacent notion of democratic quality as separate and distinct from democratization. The assumption is that democratization will succeed only if high quality democracies are targeted earlier rather than later. According to this degreeless understanding, low quality democracies might not be democratizing at all, and transparent and accountable systems with minimum corruption are seldom non-democracies—even when procedurally deemed undemocratic or of a certain degree of democracy.

THE MODEL: CONCENTRIC CIRCLES OF DEMOCRATIZATION

Democratization emerged as an independent field of study with the transitology literature of the 1980s; however, this is not the first time that scholars have addressed democratization. The search for understanding the nature and processes of democratic governance, including a democratic regime, government and state, was very much the spotlight of policy-makers and scholars during the first decolonization wave in the 1950s and the Cold War. The early studies that covered democratization did so only indirectly, however, and as part of their larger quest to understand economic development. Joseph Schumpeter, Friedrich Hayek and Karl Polanyi offered some initial perspectives on democratization as an upshot of socioeconomic development.

Having started as a corollary of economic development, democratization was mostly studied from structural perspectives. The move from economic to social structures and from there to political systems, state institutions, individual elite negotiations and social movements can be visualized through the model of concentric circles of democratization. The direction of the dominant perspectives is from the outer layers of structures to individual action and attitudes, with intermittent spikes to adjacent or outer circles. The counter-moves back to mid-circles of institutional analysis in the 1990s, and the eclectic focus of the last decade on socioeconomic structures, history and civil society show that democratization studies are at a crossroads. A useful exercise for democratization studies could be to find those elements that are significant across all layers of the circles of democratization rather than simply combining different layers of analysis. The Concentric Circles Model of Democratization is depicted in Figure 1.2.

Genesis at the Outer Circles: Democracy as a Corollary of Economic Structures

As early as 1942 Schumpeter constructed his theory of democracy in his Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Although democratization was not his immediate concern, Schumpeter offered the most influential definition of a procedural democracy. He equated it with competitive elections toward the selection of a government. He enumerated five conditions to make a democracy successful over time: high quality and resourceful politicians and political institutions; an independent judiciary; a cohesive and well-trained bureaucracy; transparency and honesty; and tolerance for differing points of view (290).

Figure 1.2 Concentric Circles of Democratization

Schumpeter’s contemporary, Hayek, also associated democracy with competition, albeit of a different nature. His model of democracy revolved around free markets and market-based competition rather than electoral contestation. It required a comprehensive rule of law system seeking to limit arbitrary government interference in the economy, and the expansion of individual freedoms, including, notably, entrepreneurship. Their differences notwithstanding, both Schumpeter and Hayek were interested in understanding development rather than elucidating how democracies develop overtime. For Schumpeter, elections sufficed to qualify a regime as a democracy. For Hayek, free markets were enough to instill and safeguard democracies.

Individual initiative and free markets were nowhere enough for democratization according to Hayek’s contemporary, Polanyi (1944). He argued that the only way to advance freedoms in societies toward greater democratization was to countervail the market-propelled inequalities with social reforms, including particularly distributive policies.3 As a precurso...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Concentric Circles of Democratization: Teasing Out the Common Drivers

- Chapter 2: The Transparency Triangle: Differentiating Inputs, Outputs and Outcomes

- Chapter 3: The Accountability Cube: Moving from Dichotomy to Continuity

- Chapter 4: The Corruption Pentagon: Linking Causes, Controls and Consequences

- Conclusion: Toward a Substantive Democracy

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index