This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How to be Critically Open-Minded: A Psychological and Historical Analysis

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In a lively and subversive analysis, psychologist John Lambie explains how to see another person's point of view while remaining critical – in other words how to be 'critically open-minded'. Using entertaining examples from history and psychology, Lambie explores the implications of critical open-mindedness for scientific and moral progress.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access How to be Critically Open-Minded: A Psychological and Historical Analysis by J. Lambie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

How Is Human Progress Possible?

On 5 July 1687, Isaac Newton published his great work, the Principia Mathematica. In it he provided, among other things, the most accurate model of the solar system in human history to date. Newton’s account of the laws governing the movement of bodies both on Earth and in the heavens was much more accurate than that given by Aristotle 2,000 years earlier, and was an improvement on Galileo’s theory of 50 years previously.

Two years later, in December 1689, the English Parliament passed the Bill of Rights. This curtailed the power of the King, increased the freedom of Parliament, and enshrined certain basic rights for all English subjects, including the freedom from “cruell and unusuall Punishments”. This last provision effectively outlawed torture, which had been prevalent in England during the Middle Ages and in the Tudor period.1

Although these two publications are not directly linked, they both represent progress, in two separate domains. Newton’s book represents progress in our scientific knowledge of the universe, and the Bill of Rights represents progress in ethics.

But how is such progress possible? What explains it? Some people argue that we should be very wary of the idea of progress, saying that it is very easy to slip into the fallacy of assuming that it is somehow inevitable, that the story of humankind is the story of necessary increases in liberty, enlightenment, and scientific knowledge (the so-called “Whig interpretation of history”). But when I talk of progress, I am not implying inevitability at all. Things can, and often do, get manifestly worse as well as better over time. I am simply referring to how something changes relative to a particular valued standard: if it gets nearer to that standard, then we have progress; if it gets further away from that standard, we have regress.

It is relatively easy to identify a standard for progress in knowledge, but perhaps it is harder when it comes to morality. With regard to knowledge, progress occurs when our representations of the world become increasingly accurate, that is, when our models and representations of the world more closely correspond to reality. For example, a ten-year-old child has more accurate representations of the world than a one-month-old baby, and astronomers today have a more accurate representation of the universe now than anyone had in 1600. Over historical time, knowledge does not necessarily increase – for example, Christopher Columbus’s calculation of the circumference of the Earth in 1492 was vastly inferior to the incredibly accurate measurements of the Greek astronomer Eratosthenes 1,700 years earlier2 – but there are pockets of human history during which we can see definite increases in scientific knowledge.

With regard to moral progress, I simply mean the increasingly humane and fair treatment of other human beings. There have been definite periods in history when moral progress so defined has occurred. For example, the abolition of slavery, the outlawing of torture, the provision of welfare to the sick and needy, and the acknowledgement that genocide is wrong are clear examples of moral progress in this sense. Of course, things can easily move in the other direction – Nazi Germany was morally regressive compared with the Weimar Republic, slavery was reintroduced in the French colonies in 1802 by Napoleon after it had previously been outlawed during the French Revolution, and a number of US lawyers and politicians condoned torture in Guantánamo Bay in 2002, more than 200 years after it was outlawed by the US constitution.3 But, again, we can observe ethical progress in particular cultures over certain time intervals, even if that progress can also be reversed.

Whether or not people agree with my definitions of progress, there is still objective sense to my question – how does movement towards those standards I have just outlined occur? Progress is certainly not inevitable, and it can be reversed, but it does happen and it is not completely random. On the contrary, it occurs because individuals or groups of people explicitly work towards a goal of progress – for example, Galileo, Kepler and Newton were explicitly aiming at a more accurate model of the solar system, and ethical leaders such as Jesus, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King were explicitly aiming at fairer and more compassionate societies.

An obvious objection to my question at this point is: aren’t there two questions here, rather than one? Aren’t knowledge and morality two completely different domains, and won’t there be two completely different stories about the processes which underlie scientific knowledge and those which underlie moral progress? A popular answer to my question is that science is based on our intellectual capacities and morality is based on our emotional or religious sensibilities. For example, in this view scientific progress is based on our rationality and our high-level cognitive skills, whereas moral progress is based either on the cultivation of emotions such as pity and compassion, or on religion, perhaps religious feelings, or on following religious injunctions to be good.

I shall show that this view is mistaken. On the contrary, I shall argue there is a single psychological capacity that underlies progress in both knowledge and ethics. Another objection is: why look for a psychological capacity? Two other kinds of explanation present themselves, namely, biological and cultural. Biologists may argue that there is some innate capacity or structural feature of the human brain that enables “cognitive flexibility”, for example, and that this biological feature underlies scientific progress. Of course, on one level, any psychological capacity is itself underlain by biological structures (but also by cultural ones) and so there is always a biological substrate to any psychological capacity. But on the other hand, biology and evolution by natural selection are not good candidates for answering my question. Evolution by natural selection is much too slow to account for the changes that I am concerned with. Scientific progress has been a feature of only the last 2,000 years of human history, and the major advances have taken place only in the last 400 years. This period of time represents too few generations for evolution by natural selection to be a major factor. And, as for moral progress, this seems highly culture-bound and precarious. It is easy for a single generation to become morally barbaric. We seem to have biological impulses for aggression at least as much as we do for love and compassion.

Furthermore, by looking at the fossil record, we can see that anatomically modern humans, with brains much like ours, were around 150,000 years ago. Many cultural revolutions have taken place over the past 100,000 years – the so-called “great leap forward” of 40,000 years ago when we see more sophisticated tools and representational art,4 the birth of agriculture about 10,000 years ago, the invention of writing about 6,000 years ago, and the industrial revolution of about 250 years ago – but these have not all been associated, so far as we know, with direct biological transformations in brain structure or genetics.

So, if biology isn’t the answer to our question, is culture? Do cultures and societies provide the conditions under which scientific and ethical progress occur? Of course, the answer must be yes. How could it be otherwise? For example, if your society forbids you from taking seriously the idea that the Earth moves and goes around the Sun, as happened in Galileo’s time, or forbids you from investigating genetics (as in Stalin’s Russia) or “Jewish physics” (as in Nazi Germany), then obviously this will hinder progress. Conversely, if your society encourages freedom of thought and investigation, then this will surely facilitate scientific progress. And likewise, ethical progress can only occur under certain cultural conditions. For example, certain political and economic conditions were necessary for progressive acts, such as women gaining the vote (e.g., cultural shifts as a consequence of the First World War), or the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa (e.g., economic and cultural pressure from the international community).

However, there is an interaction between the cultural and the psychological. By “cultural”, I mean the social, political and material conditions one lives under, and by “psychological”, I mean the experiences and thoughts of individual people. The cultural and the psychological both affect one another, and when we investigate this interaction we can choose where to focus our attention.

For example, let’s say we were to investigate the scientific revolution of 17th-century Europe. For the sake of argument let’s suppose that we discover, on the basis of extensive research, that this revolution was founded on political factors such as the growing imperialism and capitalist economy of Europe, and also on the social changes instigated by the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. This may be true, but there is also a psychological level of interest that interacts with, and affects, this cultural level. For example, how did individual people experience their world, how was this affected by the Protestant Reformation, and how did this in turn affect how they chose to investigate the world around them, or indeed how they chose to behave towards their fellow human beings?

Such an account could go from the cultural level (the Reformation) to the psychological level (change in thinking patterns) back to the cultural level (the rise of Capitalism). But, since the individual and culture are in constant interaction, we can equally start with the individual and ask, for example, what changes in thinking style were responsible for the Reformation, even though we might still go back further and ask about which cultural changes were responsible for those changes in thinking style, and so on.

So, we have a legitimate aim to look for a psychological explanation for human progress. Such an explanation is not the “ultimate” explanation – the psychological must have a biological basis, and it must also be influenced by culture, but it is meaningful and important and, if we are concerned with how to encourage progress, it provides a good entry point for action and behaviour change.

Part of the psychological explanation for human progress must be our intelligence and our “imagination” – but these are both much too general to be the answer we are looking for. We can imagine manifestly false theories and imaginatively devise cruel tortures just as much as imagine accurate theories or kind ways of treating people. Imagination is underlain by working memory – the ability to hold information in mind and manipulate it – and although this may be necessary, it is not sufficient to be the psychological mechanism underlying progressive development in the domains we are concerned with.

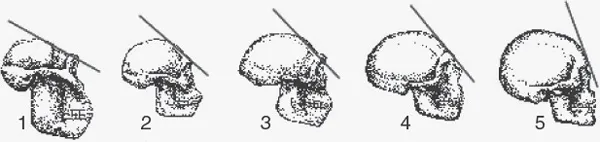

To see why, consider human evolution. Working memory is underlain by the prefrontal cortex5 and, although the prefrontal cortex has increased in size during human evolution, it had already reached its present size by about 150,000 years ago.6 The prefrontal cortex in humans is more highly developed than in other primate species. (See Figure 1.1, which illustrates a greater prominence to the prefrontal cortex in hominid evolution.) Indeed, the ratio of the prefrontal cortex to the whole brain has been calculated in Homo habilis to be 83% of the ratio in the modern brain, showing that there was an increase in the size of this part of the brain over the two million years between Homo habilis and Homo sapiens sapiens.7

But although our modern human species has existed for 150,000 years, there is little in the fossil record to give hard evidence that we were using complex working memory and executive functioning at this time, although a lack of evidence of course does not necessarily mean it was not present. Executive functions are related to working memory and include “mentally playing with ideas, giving a considered rather than an impulsive response, and staying focused”.8 Coolidge and Wynn (2001) looked at archaeological artefacts and estimated whether executive functions such as sequential memory, task inhibition, organization, or planning would be needed to make them. They concluded that nothing in the archaeological record of early human history before 40,000 years ago appears to require executive function. Indeed, one study which recorded the brain activity of people learning to make stone tools of the kind seen in the earliest archaeological records found brain activation in the perceptual-motor regions of the brain, but no activation in the dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex.9

Figure 1.1 The increasingly high, straight forehead during human evolution suggests an expansion of the prefrontal cortex

Key: 1. Australopithecus robustus; 2. Homo habilis; 3. Homo erectus; 4. Homo sapiens neanderthalensis; 5. Homo sapiens sapiens. (Figure reproduced with permission from www.thebrain.mcgill.ca).

The revolution in human culture that occurred about 40,000 years ago may, according to some, have been due to an increase in our working memory ability.10 There is no direct evidence for any shift in brain anatomy at this time – fossil skulls of humans from 40,000 years ago do not show any evidence of a larger prefrontal cortex than those of 100,000 years ago but perhaps, the argument goes, there were “soft” changes in the internal connectivity of the brain which wouldn’t show up in the fossil record. Around 40,000 years ago there was the first appearance of representational art and more sophisticated tools. Mellars (1996) argues that the tools at this time were much more standardized – whereas earlier stone tools seem to conform more to the natural shape of the flake from which they came, these tools suggest that the maker has invested effort in modifying the original shape of the stone flake in order to achieve a distinctive and standardized form. If this is correct, then the manufacture of such tools would need to be guided by an ideal form held in mind before and during production, in order to guide and regulate the manufacture of the tool.11 In other words, this is evidence of the use of working memory.

A particularly striking piece of physical evidence for the use of working memory function is the Lion Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel.12 This is a small mammoth ivory statue of a human with a lion’s head that has been dated to 32,000 years ago, making it one of the oldest pieces of art in human history (see Figure 1.2). Since the statue represents something that does not exist in the world, its maker must have held two concepts in mind – person and lion – and merged them, and then used this new concept to guide the manufacture of the statue. This has been described as “the oldest convincing evidence for modern [working memory] executive functions yet identified”.13

But having a good imagination and being able to make imaginative art such as the Lion Man is not enough for progress in the sense being discussed here. For example, imaginatively believing that the Sun is pulled by a sky-chariot is not “an accurate representation”, to quote what was said earlier. What else is needed? At the very least people must be able to hold the critical attitude that the “what is not” of imagination may be better or worse than the “what is”. The “what is not” – the alternative theory, or the point of view of the other – may be more accurate than my theory or my point of view. In other words, people need to be aware of the limitations and the fallibility of what they currently believe; they need a notion that their current beliefs are improvable.

Figure 1.2 The 32,000-year-old Lion Man Statue of Hohlenstein-Stadel (photo: J. Duckeck, Wikimedia Commons)

One way to explain this is to reverse tack and consider why progress is relatively rare, and why we often regress. It is worth reiterating the point that the kind of thinking I am talking about is not necessarily adaptive from an evolutionary point of view. Normally, most animals do not detach from and criticize their current point of view, and such a stance has its costs as well as its benefits. Evolutionary psychologists often make the point that the “cognitive niche” we have entered with our flexible thinking skills is a highly complex and precarious environment to live in.14 What they mean by this is that all other animals – including us – mainly manage their perceptions and control their behaviour using highly specific and largely automatic and quick processing systems, rather than their imagination. For example, fear and disgust are mostly automatic and highly specialized systems for detecting and responding to danger and toxins, respectively. If we only had a general-purpose capacity for reflective thinking and had to consciously and laboriously work out whether or not each situation we faced was dangerous or not, we would not survive long. Most of the time it is too slow and costly to engage in “creative thinking”. As the evolutionary psychologists Cosmides and Tooby write: “the costs and difficulties of the cognitive niche are so stringent that only one lineage, in four billion years, has wandered into the preconditions that favore...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. How Is Human Progress Possible?

- Part I: Critical Open-Mindedness: What Is It?

- Part II: Critical Open-Mindedness: What Is It Good For?

- Part III: Critical Open-Mindedness: What Underpins It?

- Part IV: Implications and Conclusions

- Notes

- References

- Index