eBook - ePub

Great Power Peace and American Primacy

The Origins and Future of a New International Order

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book explains the period of great power peace in the last fifty years and outlines the path to perpetuating it. Drawing on the Realist tradition and challenging conventional wisdom about the causes of American primacy, Baron explores contributions to peace made by the balance of power, nuclear weapons, democracy and globalization.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Great Power Peace and American Primacy by J. Baron in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Relazioni internazionali. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Transformation of Great Power Politics

Imagine that instead of dying in 1715 of gangrene, Louis XIV, the former ruler of France and one of the first modern heads of state, had been cryogenically frozen. Further suppose that he was reawakened in the early 21st century and his life was extended long enough for him to be brought up to speed on the nearly 300 years of history that had elapsed since his hibernation began.

At first glance, much about the international system would be recognizable to the Sun King. Most significantly, the state, whose power Louis helped consolidate away from the overlapping authorities of feudalism, remains at the center of politics. New organizations like the United Nations and the European Union play important roles, but it is still primarily up to individual governments to provide stability within their borders and to figure out how to defend against attacks from outsiders, be they other countries or terrorist networks. Governments still conduct diplomacy, sign treaties, exchange ambassadors, make threats, build armies, impose regime changes, set tariffs, battle pirates, and form alliances. Overall, there would be an important extent to which things would look, act, and feel quite familiar.

Despite these elements of familiarity, Louis would recognize two main ways in which the relationships among the most powerful countries in the world have transformed since his reign. First, the great powers do not fight wars against each other, and do not even approach the precipice. In fact, there are a group of great powers, including France, who no longer threaten the use of force against each other. Second, the United States is by far the most dominant military power on the face of the earth. While in Louis’s time the great powers copied the military capabilities of each other to the greatest extent possible, America possesses an armed force unlike any of the other great powers.

This chapter will make the case that a transformation of great power politics has occurred since the time of Louis XIV, and will outline its main features. Before doing so, I will define the term “great power,” as well as which nations have met this definition in the last half millennium.

I. The modern great powers

The notion of great powers is not a new one. As long as humans have grouped themselves into political units – be they tribes, clans, principalities, and so on – some have mattered more than others. There were dozens of Greek city-states, but Athens and Sparta shaped Hellenic life. In most cases, the preferential role of the great powers has been the consequence of their capacity to use force better than their peers: to protect and to kill, to defend and to destroy. Even when they adopted more peaceful means of exercising control, their potential to physically dominate was not too far beneath the surface.

Great powers then are those countries that disproportionately affect the likelihood and consequences of war and peace.1 Most importantly, their foreign policy decisions are integral to global stability. When the great powers go to war, they bring the most advanced weaponry available at the time, with the most sophisticated means of utilizing it. The effects can extend well beyond their people and territory. Indeed, the core attribute of a great power is its ability to interfere in the lives of others, whether for good or for ill.

One way to try to understand where each state fits on a spectrum of “greatness” of power is to think about what would happen if its government was determined to take control over as much of the world as it could while everyone else tried to contain it. In other words, imagine what would happen if each country took a turn at being a “rogue state.” The vast majority would not be able to create mass instability on their own. A Hitler-like ruler in Belize, in Thailand, or even arguably in Italy would be relatively limited in the havoc they could wreak. The same cannot be said about Russia or America, or – given their economic and technological strength – Germany or Japan. If any of these nations adopted a militaristic and expansionist posture, their neighbors and even those further away would start getting very worried.

This book will focus on the modern era of great power politics. Modernity is one of those concepts that can mean something different to everyone. I mean it in the sense of a world that looks and feels roughly similar to the one that we currently occupy. The most basic fact about political life today is that it takes place between a group of independent and territorially defined states. Each of us lives within one of these states (or one of its possessions), and the boundaries between them are more or less clear. The same could not have been said during the feudal era that preceded the rise of the territorial state, when individuals had multiple and at-time competing loyalties to entities that provided varying degrees of security. Though there is not universal agreement on what marks the transition, the historical consensus suggests that the origin of the modern era in Europe should be dated at approximately 1500.2

So, which countries have played the most central role in international stability for the last 500 or so years? There is general alignment among academics about the composition of the great power group during the modern era.3 I follow that consensus, with the important exception of the treatment of Germany and Japan after 1945. The standard view is that Germany and Japan lost their great power status at the end of World War II, and did not regain it until 1991. I believe that is mistaken. While both countries unconditionally surrendered to end World War II and lost their status as sovereign states – let alone great powers – they each regained their central role in global stability far before 1991. Indeed, the fate and future of Germany, and most importantly of its conventional and especially nuclear capabilities, was the most serious point of contention between the superpowers, and the most likely path to World War III. Japan has played a similarly key role in Asia. Its actions were closely monitored, and the stability of Asia has had much to do with the policies adopted by its government. For the time between 1945 and 1991, the decisions made by Germany and Japan were absolutely central to global order.

Furthermore, on almost any measure of power, Germany and Japan ranked near the top long before the 1990s. Since the early 1960s, their GDPs have been larger than any country’s other than the superpowers. They also have had tremendous international influence despite a limited ability to project military force abroad. For example, as of 1975 Germany provided more overseas development assistance (ODA) than France, and Japan provided more than Britain. By 1980, Germany and Japan were providing significantly more ODA than any member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development other than the United States. Guns and tanks are not the only way to make friends and influence people, and on these other dimensions Germany and Japan quite clearly met the criteria of states having global reach. And it would be wrong to refer to Japan and Germany as strictly “civilian powers,” as some have.4 Both had developed large military machines well before 1991. In sum, one cannot tell the story of great power politics in the second half of the 20th century without including these two nations.

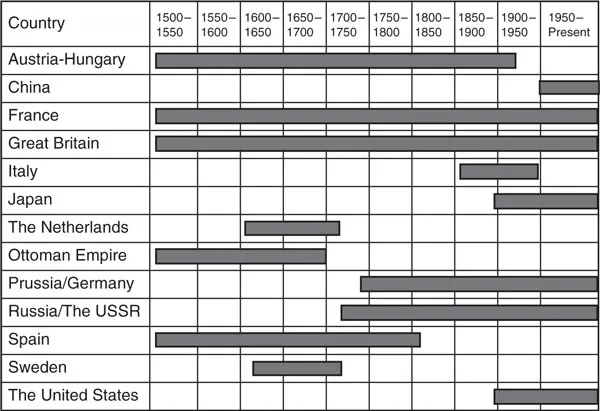

With those points in mind, Figure 1.1 shows the membership of the great power club since 1500:

Figure 1.1 Great powers: 1500–Present

The list of great powers in contemporary international society consists of China, France, Great Britain, Germany, Japan, Russia, and the United States.

II. A historic achievement: Great power peace

Arguably more than anything else, warfare has defined the relations among great powers in the modern era. The possibility that war could take place cast a shadow over international politics, and it involves little exaggeration to suggest that almost every foreign policy action of these states – as well a substantial number of their domestic political decisions – was made in order to prepare for wars, prosecute wars, or was affected by the potential of wars.

The current time of great power peace stands in stark contrast to this history. Since 1953, no war among these states has taken place, the longest such period in modern history by a considerable margin. While this development is momentous, especially in light of what a great power war would have meant for the world in the last 50 years, it does not indicate the most unique way in which times have changed. In previous periods of peace, even when states did not fight, they approached the abyss of all-out hostilities with some regularity. During the last 30 years of the Cold War, in clear contrast to the first 15, there was no moment where the potential for war over a political disagreement hung in the balance. A subset of the great powers has taken this notion of peaceful rivalry several steps further. For them, the specter of conflict no longer affects their interactions with each other.

A. The absence of war

War among the great powers was common from the beginning of the modern era through the first half of the 20th century. Between 1500 and 1953, there were 64 wars in which at least one great power was opposed to another, and they averaged a little more than five years in length. In approximately a 450-year time frame, on average at least two great powers were fighting one another in each and every year.5 Over the same period, significant stretches of peace were relatively infrequent. The average gap between great power wars was a little shorter than a decade. In fact, from 1500 to 1954, there were only four recesses from war longer than ten years: 1764–1777, 1816–1852, 1872–1903, and 1922–1938. The longest of these periods was 37 years, following the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. We therefore are currently experiencing the most prolonged era without war among great powers in the halfmillennium that states have dominated the political landscape.6

B. Rivalry without crises

While previous times of peace faced recurring crises, the current period has not faced such a dangerous moment in over 50 years. A dispute between governments turns into a crisis when each side, “indicates by its actions its willingness to go to war to defend its interests or to obtain its objectives.”7 A crisis exists when there is a moment in the dispute where the possibility of a resort to war becomes apparent to both parties.

The periods 1816–1852 and 1872–1903 witnessed multiple crises. The post-Napoleonic peace included the “Belgian crisis of 1830, the Near Eastern crisis of 1838, and the first Schleswig-Holstein crisis of 1850, to mention only the uglier disputes of the period.”8 The peace from 1872 to 1903 also had frequent moments when war seemed likely. For example, there was the British-Russian crisis in 1877–1878, the Fashoda crisis in 1898 between Britain and France, and the two Moroccan crises between Germany and France (along with Britain in the latter) in 1904–1906 and 1911, respectively. While war was avoided in all of these situations, almost always the precipice was approached at least once every decade.

The first 15 years of the Cold War had a similar tenor, witnessing a series of showdowns between the Western allies and the Soviet bloc. Most notable in this group were the Berlin Blockade (1948), the Berlin crisis (1961), and the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962). However, after 1962, there was no moment where the various disputes of the Cold War reached a crisis point.9

The absence of war is not the same as peace. Peace implies some willingness to accept the status quo, however begrudgingly. War can be avoided for some period of time by rivals that do not accept the status quo, just as one can go a few rounds of Russian Roulette without finding the bullet. But the tension never leaves. This is why the modern period of great power peace truly starts after the Cuban Missile Crisis. Before that incident, the Cold War was a series of crises, close calls, and confrontations. It was not peace, merely the postponement of active hostilities. What made the Cold War rivalry unique after 1962 was not that the blocs avoided war but that they managed to do so without even approaching the brink of it.

C. A state of peace

Even if disputes do not escalate into crises or wars, countries can still live in an environment where the threat of antagonism affects nearly everything they do. Immanuel Kant described this as a “state of war,” which “even if it does not involve active hostilities, it involves a constant threat of their breaking out.” In contrast, states can also operate in a “state of peace,” which is not only a “suspension of hostilities” but also a time without even threats of the use of force.10 In a state of peace, countries go about their daily business without worrying about the possibility that any disagreement that they might have could escalate into conflict. The current period of peace differs from any other in modern history because a subset of the great powers – France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, and the United States – have attained such a condition. Force is no longer a tool for resolving disputes among this group....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Seasons of Darkness and Light

- 1. The Transformation of Great Power Politics

- 2. A Theory of Order: Explaining Major Change in International Politics

- 3. A Season of Light: The Balance of Power and the Westphalian Order

- 4. A Fifty Years’ Crisis: The Collapse of the Westphalian Order and the Path to Total War

- 5. Dawn of a New Day: The Rise of the American Order

- 6. Getting MAD and Even: Nuclear Weapons, Bipolarity, and a New Kind of Rivalry

- 7. Balance of Power and Its Critics: The Limitations of Current Paradigms

- 8. Preserving Peace in the 21st Century: Thought and Action in a Newly Ordered World

- Conclusion: The Need for Vigilance and Sacrifice

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index