eBook - ePub

The Emblematic Queen

Extra-Literary Representations of Early Modern Queenship

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Emblematic Queen

Extra-Literary Representations of Early Modern Queenship

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This study examines representations of early modern female consorts and regnants via extra-literary emblematics such as paintings, jewelry, miniature portraits, carvings, placards, masques, funerary monuments, and imprese.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Emblematic Queen by D. Barrett-Graves, D. Barrett-Graves in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

CATERINA CORNARO, QUEEN OF CYPRUS*

Liana De Girolami Cheney

Caterina Cornaro (1454–1510), queen of Cyprus, a nobil donna,1 was born on November 25, 1454 (Saint Catherine’s Day) in Venice and died on July 10, 1510, in Venice (see figures 1.1–1.5). She came from a powerful family of the Republic of Venice, the Cornaro family. Caterina was the daughter of Marco Cornaro (1406–1479), knight of the Holy Roman Empire, and Fiorenza Crispo, a Greek princess, daughter of the Lord of Syros, Nicholas Crispo, and granddaughter of John Comnenus, emperor of Trebizond. This remarkable Cornaro family produced four doges, including Marco Cornaro, doge of Venice from 1365 to 1368.2

During her lifetime, Caterina excelled as a queen, a humanist, and a patron of the arts. Educated in the Benedictine convent of Saint Ursula in Padua, Caterina learned to be a cultivated woman. She had five younger sisters, Violante, Cornelia, Marietta, Bianca, and Lucia, and two brothers, Luke and George. The five sisters attended the Benedictine convent, while the brothers were educated in a military academy. At the age of 18, Caterina was viewed as a bella donna (“beautiful woman”) as well as a nobil donna (“noble woman”). In chronicles, she is described as being of medium stature, with deep brown eyes, a rosy complexion, and reddish curly tresses bleached by the sun. She was praised for her vivacious nature as well as her gentle and courteous disposition.3

The Cornaro family included not only noblemen, military, and political officials, but exporters and merchants as well. They had close commercial ties with Cyprus, administering copper and sugar-mills and exporting other Cypriot goods to Venice. The Venetian trade in the Mediterranean Sea, in particular with Egypt, was significant with exchanges of spices, sugar, salt, wheat, copper, precious stones, and brocades of gold and silver.4

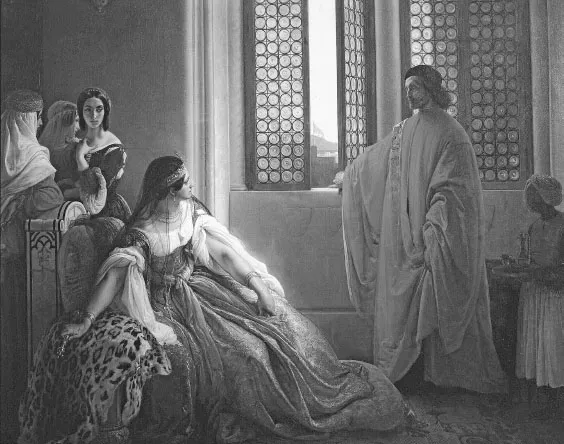

Figure 1.1 Francesco Hayez, Caterina Cornaro Deposed from the Throne of Cyprus, 1842, reproduced by kind permission. © Carrara Academy, Bergamo. Photo credit: Alfredo Dagli Orti. The Art Archive at Art Resources, NY (AA 346714).

Figure 1.2 Antonio Vassilacchi (Aliense), Disembarkation in Venice of Caterina Cornaro, Queen of Cyprus, 1620s, reproduced by kind permission. © Correr Civic Museum, Venice. Photo credit: Cameraphoto Arte. The Art Archive at Art Resources, NY (ART 166870).

Figure 1.3 Jan II van Grevenbroeck, Caterina Cornaro, 1800s, reproduced by kind permission. © Correr Civic Museum, Venice. Photo credit: Gianni Dagli Orti. The Art Archive at Art Resources, NY (AA 370067).

Figure 1.4 Gentile Bellini, Caterina Cornaro, Queen of Cyprus, 1500–1505, reproduced by kind permission. © Magyar Szépmùvészeti Múzeum, Budapest, Hungary. Photo credit: Magyar Szépmùvészeti Múzeum, Budapest/Scala. The Art Archive at Art Resources, NY (ART 398924).

Figure 1.5 Giorgione/Titian, Caterina Cornaro, 1542, reproduced by kind permission. © Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Photo credit: Alinari. The Art Archive at Art Resources, NY (ART 55220).

On July 30, 1468, the prosperous Cornaro family consented for Caterina to marry James II (1438–1473) of the prestigious Lusignan dynasty in order to augment and expand their capital and commerce with the coast of Levant.5 James was king of Cyprus and Armenia (nicknamed James the Bastard). The union between Caterina and King James II was well orchestrated by Caterina’s father, Mark Cornaro, and uncle, Andrew Cornaro. The ongoing commercial and monetary exchanges between the Cornaro family and the king of Cyprus facilitated the contractual arrangement. The Cornaro family provided a large dowry of 100,000 ducats, a beautiful young lady, and further commercial connections in the Mediterranean. King James II was the illegitimate son of John II, king of Cyprus, and his Greek mistress Marietta de Patras (d.1503).6 John II’s marriage with Helena Palaiologina (1428–1458), a Byzantine princess of the Paliaologos family, provided eastern commercial connections as well social and cultural prominence.

The proxy marriage took place when Caterina was only 14 years of age. The Cypriot ambassador, Philippe Mistachiel, represented King James II, and Doge Francesco Foscari performed the prenuptial ceremony in the Basilica of San Marco in Venice. Four years later, in 1472, Caterina traveled to Cyprus and officially married King James II, in the cathedral of St. Nicholas in Famagosta, the capital of Cyprus. Before traveling to Cyprus, an extravagant ceremony was performed before the high altar of the Basilica of San Marco, establishing her as queen of Armenia, Jerusalem, and Cyprus.7

The Bucentaur, the Venetian majestic state barge, awaited Caterina in front of her father’s palace, Palazzo Cornaro in San Polo, where she appeared in white and gold regal attire; accompanying her was the doge, Nicolò Tron. As the Bucentaur moved across the Grand Canal to reach the Basilica of San Marco, people chanted prayers of good wishes.8 Caterina’s fanciful ceremonial attire for the nuptial event contrasted with her simple, elegant, and typical mode of dress. Following the Venetian ethical and cultural costumes, she sometimes wore a gold or silver chain with a cross.9

Soon after the wedding, Caterina’s husband died under mysterious circumstances. In a hunting outing in late June 1473, with his Cypriot court and invited members of the Cornaro family—Andrew Cornaro, Caterina’s uncle, and Mark Bembo, Caterina’s cousin—King James II developed dysentery. This inflammatory disorder of the colon was caused by poison. He died nine days later, a convenient event for the Cornaro family, who, when planning the marriage of Caterina with King James II, knew that in the event of the king’s death, Caterina, as a widow and as queen of Cyprus, would become by legal right sovereign of Cyprus, and the Cornaro family would be able to maintain and expand their trade with Cyprus, as well as control the commercial balance of power in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. This event created a potential legal claim of Cyprus for the Cornaro family and indirectly for the Venetian Signory (The Council of Ten). According to the diplomatic rules and alliances, the Venetian Signory could not govern a foreign state, but by adoption could inherit the rights to rule another state.10 In Caterina’s case, being a daughter of the Venetian Republic on her death, La serenissima Venice would inherit Cyprus.

At the time of her husband’s sudden death, Caterina was pregnant, thus providing a future heir for the Lusignan dynasty and the Cyprus sovereignty. But under mysterious circumstances, James III, Caterina’s one-year-old son, died in August 1474.11 With his death, the Lusignan dynasty was over.

With difficulty and strong supervision by the Venetian Signory and Senate, Caterina ruled Cyprus from 1474 till 1489, when she was ungraciously deposed of her queen’s power by her own Venetian family. During her reign as queen of Cyprus, the Venetian Signory, eager to obtain control over Cyprus, ordered her father, Mark Cornaro, to reside in Cyprus and assist her in the affairs of the state. Another goal was to prevent any marital proposal that would avert the Venetian Signory from obtaining possession of the Cypriot estate. Friction between father and daughter constantly interfered with the governance of Cyprus, providing more power for the Venetian Signory to indirectly govern the affairs of the Cypriot estate.12

Without a Cypriot heir on the throne, Caterina was vulnerable. Her family and the rulers of the Republic of Venice were fearful that she might marry one of their powerful political adversaries who were courting her, such as the king of Naples and the sultan of Egypt. In 1486, the Venice Signory persuaded Catherine’s mother, Donna Fiorenza, to travel to Cyprus to convince her daughter to resign as queen and return to Venice. In 1498, frustrated and concerned by the successful power exercised by Caterina as sovereign and diplomatic ruler of Cyprus as well as witnessing the strong support of her subjects, the Venetian Signory sent another emissary from the Cornaro family, Caterina’s brother, Giorgio Cornaro (1452–1527), to Cyprus to convince her to abdicate. Eventually, Caterina was forced to resign and leave Cyprus, to save the honor and prevent the destruction of her family.13

Interestingly, the tragedy of this moment was portrayed many times in performances and in the visual arts of nineteenth century. In Caterina Cornaro Deposed from the Throne of Cyprus of 1842 (figure 1.1), Francesco Hayez (1791–1882) excelled with an operatic effect in a painting depicting the expulsion of Caterina from Cyprus by her brother, Giorgio Cornaro. In his Memoirs, Hayez described the composition of the painting and cited the date of its completion.14 The scene took place in an interior setting—architecturally resembling a room in a Venetian palace—where her brother, opening a window, points to a Venetian flag with the Lion of San Mark flying over Caterina’s Cypriot castle. Hayez depicted Giorgio Cornaro, wearing a cloak with bright red colors, as an emaciated elderly man with a severe face and stern gaze to express the cruelty of the moment. In contrast, he portrayed a young and beautiful Caterina, dressed in royal blue and white brocades, who responds with astonishment and surprise. In her spontaneous reaction, she tilts over her armchair and drops her scepter, a symbol of her royal power. Her golden chain with a large crucifix rests on her lap, an artistic allusion indicating that now only her Christian faith will sustain her.

In the painting, Caterina’s maids of honor seem indifferent to the event, except one of them who gazes with evil pleasure and disdain at the fearful queen of Cyprus. In including this malevolent creature, Hayez referred to Charlotte (1444–1487), princess of Antioch, former queen of Cyprus (1458–1463) and Caterina’s sister-in-law, who plotted to dispose of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Extra-Literary Emblematics

- 1 Caterina Cornaro, Queen of Cyprus

- 2 Bejeweled Majesty: Queen Elizabeth I, Precious Stones, and Statecraft

- 3 “Bear Your Body More Seeming”: Open-Kneed Portraits of Elizabeth I

- 4 Mermaids, Sirens, and Mary, Queen of Scots: Icons of Wantonness and Pride

- 5 Martyrdom and Memory: Elizabeth Curle’s Portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots

- 6 Anne of Denmark and the Court Masque: Displaying and Authoring Queenship

- 7 “A Lily among Thorns”: The Emblematic Eclipse of Spain’s María Luisa de Orleáns in the Hieroglyphs of Her Funeral Exequies

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- Notes on Contributors

- Index