eBook - ePub

Fallen heroes in global capitalism

Workers and the Restructuring of the Polish Steel Industry

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fallen heroes in global capitalism

Workers and the Restructuring of the Polish Steel Industry

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Through the prism of 'Nowa Huta', a landmark of socialist industrialization, Trappmann challenges the one-sided account of Poland as a successful transition case and reveals the ambivalent role of the European Union in economic restructuring. An exemplary, suggestive case of multi-level analysis research.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Fallen heroes in global capitalism by V. Trappman,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

1

The Steel Sector in the Global Economy

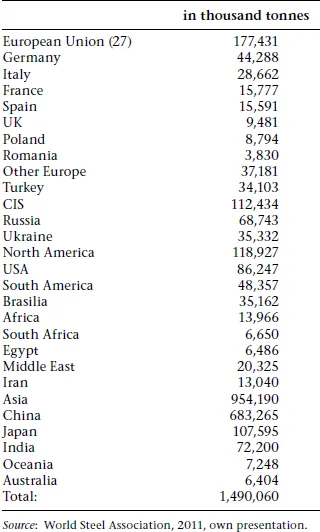

The steel industry used to be a national-level and nationalised industry, and today has become privatised and globalised. Thirty years ago, Europe was the world’s largest steel producer, with 23 per cent of total world production; today China has the largest steel production capacities, with total Asian crude steel production share at more than 50 per cent of global production (World Steel Committee on Economic Studies, 1981, 2011). In 2011, the most important crude steel producers in the world were ArcelorMittal, followed by Baosteel, POSCO, Nippon Steel, Jiangsu Shagung and Tata Steel. All these steel corporations are located in Asia, except ArcelorMittal, which was a merger between the Indian Lakshmi Mittal and the French Arcelor. This represents a dramatic shift compared to the turn of the century, when in 2000 there were at least four European corporations among the largest steel producers (Arcelor, Corus, ThyssenKrupp and Riva). Total production has also exploded, from 80 million tonnes in 2000 to 120 million tonnes in 2010. While the steel industry used to consist of many state-owned companies that answered local and national needs, today there are only a few multinationals, dominating the market. The last 15 years have seen a tremendous dynamic of fusion and mergers of companies. Observers are undecided if the mergers have already led to a global market of steel or just an international integration with regional concentration (Fairbrother, Stroud and Coffey, 2004, p. 53). An overview of steel production seems to speak for a regional concentration with the largest share of production in Asia, followed by the European Union, United States, and CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States).

In the United States, the steel industry had its heyday in the 1950s and has declined since, experiencing massive downsizing in the 1970s and 1980s: almost a quarter of a million jobs were lost during that period, with numerous communities abandoned and destroyed (Metzgar, 2000). The process started in the 1960s, when the mills began to suffer due to increased imports, a union strike lasting 116 days, and the growing popularity of substitute materials, like glass, plastics or aluminium. The mills were operating at only 39 per cent of capacity, and between 1959 and 1962, one-fifth of all steel jobs were lost. Owners invested in steel only as long as it was profitable, which meant that management pursued a strategy of de-investment and asked for wage sacrifice. Cheaper steel from Europe was threatening the US industry and trade tariffs could not prevent its decline (Hinshaw, 2002). The effect was drastic for workers and communities, with the former steel cities developing into areas of high poverty and high levels of crime (Linkon and Russo, 2002). Redundant steel workers had problems getting new jobs due to the unionisation image of steelworkers and their comparatively high income. Between 1979 and 1984, across all sectors, five million Americans lost their jobs; many did not find new employment and those who did had to work for half of their previous salary, especially manufacturing workers like steelworkers.

Table 1.1 Crude steel production in 2011

Some observers consider this period of the decline of the manufacturing sector the beginning of the rise of an underclass in the United States (Bensman and Lynch, 1988). The decline threatened the middle class and closed the door of opportunity for many lower-income Americans. While industrial jobs used to be a route out of poverty, with industrial decline, there was a dearth in jobs that provided a decent living and job security for those with a lower level of education (Bensman and Lynch, 1988, p. 205). And those who retired often did not have pensions that would cover their daily needs (Hinshaw, 2002). The Carter and Reagan administrations put in place programmes to support the sector; they mainly acted externally, restricting imports, especially of subsidised steel, and reducing the tax burden of companies. They also made some promises to redundant workers, but these were seldom kept: very few workers got the opportunity to upskill, so that in the end, even workers who had been too proud to accept public aid at the beginning eventually did apply for public aid because “being proud don’t feed your kids” (Bensman and Lynch, 1988, p. 113).

In Asia, steel was introduced as a strategic industry, with state-led development in most of the countries, considering the steel industry a prerequisite to further industrialisation. Asian steel production has shown explosive growth during recent years. Consolidation and restructuring is just about to start in many Asian countries (Sato, 2009). In particular, steel production in China has increased significantly since the 2000 due to increased local demand in the course of national economic development, GDP rise and technological innovations (Yin, 2011). Production structure has changed in favour to flat products. There are some advantages globally for Chinese steel production: the seaside location of most sites, the huge number of graduates in metallurgy and the late investments provided in the companies with the newest technologies. Problems for Chinese production are the lack of steel scrap and the increasing production capacities; each year, there is a growth of about 82 million tons of steel (Yin, 2011). First state-led attempts to consolidate the industry have for long not been successful – out of 5000 steel companies, only five produce more than 8000 tonnes of crude steel (Sun, 2007, p. 606). The Steel Industry Revitalization Plan was released in 2009 to control total output and eliminate obsolete capacity but yet without success (Tang, 2010). What might sadly help in the future is the recent initiative of privatisation in the sector which has already kicked off an open revolt of Chinese workers, beating up to death one executive in a newly privatised firm (Mah, 2011). Not are living conditions on a salary in the steel industry already too poor, the private owners even further tried to squeeze the workers. While up to now, Chinese production is locally oriented, other countries, in particular Europe, fear the rise of China’s export orientation.

Steel in Europe: the European Coal and Steel Community

The European Coal and Steel Community was the origin of Europe’s interventionist policy rooting in the Allies’ wish to dismantle and decartelise the German steel industry, in order to keep peace on the continent after the Second World War. The increasing conflict between the Allies, especially between the United States and the Soviet Union, however, led to a change in US policy regarding the de-industrialisation of West Germany, reconstruction became the main political aim (Schafmeister, 1993) and the steel industry was returned to the old owners via company shares (Schafmeister, 1993). The fear that Germany would remilitarise was appeased by the formation of the ECSC in 1952. Politically, it was a quid pro quo for France recognising Germany, and economically the policy was that competition between the companies would be reduced and cooperation enhanced (Houseman, 1991). This was quite successful during the first years of open market: increasing demand met increasing production within the ECSC. For two decades, the development of steel in Europe was expanding, predictable and relatively crisis-free (Buntrock, 2004).

Demand in crisis and overcapacities

The expansion of steel, however, led to an overproduction and Europe faced the problem of price dumping. Already in 1967, the European Commission had warned against further investments, as capacities were already considered very high. At the same time, imports from emerging markets were rising, and steel was being increasingly substituted with other materials. In the early 1980s, the capacity utilisation was only about 56 per cent, a problem leading to severe financial problems for many steel plants (Buntrock, 2004). The national governments stepped in with huge subsidies to prevent plant closures and potential job losses in locations where unemployment was already high. In some cases, the steel mills were even privatised. In France, two state firms, representing up to 90 per cent of the industry, merged into one, Usinor. Fifty-seven per cent of the sector was nationalised in Belgium and 36 per cent in the Netherlands (Conrad, 1997). In the United Kingdom, 14 large private steel companies were consolidated into British Steel, thus renationalising 76 per cent of British steel production. When national solutions did not solve the problem, the European Commission tried to intervene. The Treaty of Paris in 1951 had given the European Commission substantial power in the area of industrial policy. Under the Treaty, states were officially prohibited from subsidising the steel industry and access to outside funding for investments was restricted. All firms were obliged to communicate their investment plans to the High Authority (the precursor of the European Commission) and later to the European Commission. The European Commission was even allowed to settle minimum and maximum prices of steel and introduce production quota. These powers were not used during the 1950s and 1960s, and states regulated (and often subsidised) their individual industries as they saw fit. It was in the 1970s that the European Commission first began to use the power granted it in the 1951 treaty, introducing several industrial policy plans, each one more interventionist than its predecessor.

The Davignon Plan

In 1976, the Simonet Plan (named after Henri Simonet, responsible for industrial policy in the European Commission) introduced a strong monitoring of production, obliging companies to report their production and prices, since the European Commission was then making price suggestions. When the Simonet Plan failed,, the European Commission declared production quotas, introduced protectionist trade measures and forced subsidies and price cartels to be submitted for its endorsement under the Davignon Plan (named after Etienne Davignon the successor to Simonet) in 1977. The objective was to distribute the hardship of reduced demand for steel equally across the regions but also to prevent huge transfer payments, as had become necessary in the agriculture sector (Eckart and Kortus, 1995). Externally, the European Commission initiated and established anti-dumping taxes also as a pressure to convince other countries to voluntarily restrict their exports to Europe (Houseman, 1991).

A core element of the Davignon Plan was the so-called code on aid, signed by all countries in 1980 (Buntrock, 2004). Generally all forms of state aid were forbidden in the ECSC Treaty; however the code on aid defined conditions under which companies were allowed to receive state aid. Companies had to have restructuring plans including capacity reduction to ensure the viability of the company, because the European Commission wanted to prevent pure survival subsidies. Capacity reduction was crucial, and old plants should be closed first. The production quota was first voluntary, but when companies did not respect the agreements they became compulsory until 1988. Violation was sanctioned with financial penalties, and 100 inspectors were employed to monitor and control the quotas (Buntrock, 2004). With regard to subsidies, states did not follow the code on aid and the Commission did not really sanction the misbehaviour, but retrospectively allowed the subsidies and prolonged deadlines, legalising the misbehaviour, which in turn led to a spread and expansion of subsidies. It was also quite difficult to recognise all forms of state aid, – all forms of direct payments, tax reductions, and loans – and between 1985 and 1990, 5 billion ECU were paid in state aid without being recognised as such by the European Commission and thus were illegal (Eckart and Kortus, 1995). The important point – in relation to our main interest, the monitoring of the steel industry in Poland – is that the member states at this time ignored many of the rules and decisions of the Commission, that obedience of the code on aid was limited, and that information on production and state aid lacked transparency. In Poland, on the other hand, as we shall see, obedience of the code of aid was strictly monitored and non-application was immediately punished.

Table 1.2 Employment in the EU15 during 1975–2005, in thousands

Politically, the Davignon Plan represented a cornerstone of industrial policy in Europe. From a medium-term perspective, it was intended not only to ensure capacity reduction and the prohibition of state subsidies, but it was also intended to help guarantee the single market, modernise assets, reanimate the market and protect steel production regions by creating a social policy to assist redundant steelworkers and their communities (Houseman, 1991). On an operational level, this meant that market exit costs were redistributed among the steel plants. Countries were refunded 50 per cent of their social policy costs for workers laid off, covering training, resettlement and supplementary income programmes. Furthermore, overtime was restricted, and short-time work and early retirement were introduced to prevent further layoffs. The European Commission invested in regional development programmes (Houseman, 1991).

Economically, as an attempt to hinder market mechanisms and to have organised price building and organised competition, the results were disappointing. States just did not respect the instruments and supranational decisions and continued to subsidise their steel economies. Unfortunately, however, the national governments were not able to prevent the dramatic downsizing of the 1980s. The industry lost more than 50 per cent of its jobs during the last quarter of the twentieth century. For the individual countries in the EU15, this meant a tremendous loss of jobs.

In response, national governments tried to accelerate the provision of alternative employment, relying on generous support from the ECSC funds and some national financing to support Industrial Development Agencies to reindustrialise the affected areas. The problem was that this led to competition between regions for new industries, and the state programmes led to the conflict between labour and capital becoming one between labour and labour (Hudson and Sadler, 1985, p. 183).

In a nutshell, the supranational industrial policy failed. Despite the supranational coordinating bodies of the ECSC, many problems were tackled nationally, and the loss of employment could not be prevented. The benefit of the programmes was that ‘nobody was fired’: all workers left the industry with special programmes guaranteeing ‘socially responsible restructuring’. This socially responsible restructuring was in stark contrast to what had happened in other areas of the world, such as the United States or what would happen to the new member states of the EU with the accession of Central Eastern Europe (CEE).

The fall of communism

The fall of communism had a deep impact on Western European steel industry. First the demand from former Communist countries decreased. Second, steel products from Eastern European countries swept into a Western market, which was already suffering from its own overcapacity – imports from former Communist countries into the EU doubled. Given the lower costs of steel in Eastern Europe, competition from the steel-producing countries in CEE was clearly going to be an issue. The low-wage costs made the West afraid of losing even more jobs in the steel sector to relocation. This imbalance explains the Western steel producers’ fear of open trade relations with CEE countries. The enlargement of the EU to the East was a severe test for the sector: the West was afraid of the increase in overproduction and the lower prices of steel in Eastern and Central Europe. Hence, the steel-lobby groups of the EU15 convinced the politicians to make accession conditional on the privatisation and downsizing of the Central Eastern European steel companies. State aid should be abolished to prevent an easy modernisation of the plants and capacity reduction and employment reduction should be imposed. To illustrate the interests represented by the sector: in 2001, when accession negotiations were at their height, there were 160 million tonnes of crude steel produced in the EU15, 45 million tonnes in Germany alone; Poland produced 9 million tonnes, the Czech Republic 6 million, and Romania 5 million tonnes – all accession countries together produced a fifth of what the EU15 produced. The trade unions backed the policy of the private steel companies, so that “solidarity with eastern Europe’s steelworkers has been notable for its absence” (Bacon and Blyton, 1996, p. 776). These protective measures for the EU15 led to a wave of modernisation and mass layoffs in CEE.

Recent challenges

Accession however has not been the only challenge since the 1990s. First, technologically, the steel industry developed from low-volume, standardised production, price-competitive production to high-volume, customised, quality-competitive production. This of course had an impact on the skills and qualification required of workers, calling for multi-skilled teams, new work organisation, product innovation and specialisation. Work patterns needed to be changed that had been in place for almost 100 years in certain places (Bacon and Blyton, 1996a, oder b, p. 780). For decades, steel had been characterised by an internal labour market with rigid occupational structures and promotion on the basis of seniority; the 1990s led to a decrease in unskilled labour and an increase in the proportion of skilled, multi-skilled workers technicians and managers (Bacon and Blyton, 1996, p. 31). Thus, the new high-tech technologies and changes in work organisation have made the qualification of the workforce a major challenge for the industry, not least due to the composition of the workforce, which included a high number of workers without formal qualification and migrants who did not speak the local languages. Investments in qualification have therefore increased much more than in other sectors (Hertog und Mari, 2003).

Second, raw material provision is a huge problem. Not alone is there an increased demand in iron and ore, the 2008/9 financial crisis has also led to an increase in the value of raw material. The limited number of suppliers of raw materials, particularly iron ore, has increased their power so that historical supply chains have been disrupted. For example, China, which has a huge coal reserve, tried to limit its export quota of raw material, though it was decided unjustified by the WTO and has to be removed (Barkley, 2012). Prices are now increasingly determined by the stock market, resulting in severe short-term price fluctuations. In the long term, prices have multiplied. If one ton of iron ore cost $20 in 2000, it was $50 per ton in 1998 pre-crisis, and today it is $150 per ton. Scrap metal cost €100 per ton in 2000; in 2010 it is €400 per ton. The price for coking coal increased from $100 to $700 per ton, and for iron ore from $100 per ton to $500 per ton.

This change in raw material supply has two dramatic consequences. First, steel producers increasingly ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- Conclusion

- Annex

- Notes

- References

- Index