Role-play works because it simulates, that is, creates an illusion of real life. A role-play simulation can be so convincing as to be virtually indistinguishable from the same thing in everyday life. Therefore, we could call this simulated action a “virtual world.” If such a world does not manage to come alive and to seem convincingly real, no learning is able to take place, as the watching group will not buy into its premise. Virtual worlds are not limited to role-play, but are a hallmark of performance in general. Therefore, before we dive into role-play itself, we take one step back to the larger world from which it springs and consider the nature of the virtual worlds that lie at the heart of performance everywhere.

Role-play is a dramatic subtype of performance in general. Human beings have an impressive capacity to perform. When we do so, we select particular behaviour and emphasize it. We say and do particular things in specific situations that we otherwise might not do. We sometimes reach into our potential and release capacities that surprise and amaze us and others. Wherever it occurs, performance is marked by heightened activity.

We find performances spread all throughout human society. They include:

aesthetic performances , such as drama, dance, and music;

sporting performances of all kinds;

rites of passage, such as baptisms, birthdays, bar mitzvahs, weddings, awards ceremonies, and graduations;

social performances, such as dinner parties, trivia nights, and games of all kinds;

mini performances, such as telling a joke, or recounting a recent experience to friends or family;

professional performances in the law court, board room, and parliament;

clinical interactions in medicine, nursing, allied healthcare, and counselling.

The dramatic form called role-play is performance in the educational domain.

Performances are played out in the midst of what we call real life, the common round of actions that make up our working, social, and personal lives. Real life or reality is a fairly loose term. A professional consultation is real in that loose sense, and that understanding lies behind the complaint heard muttered from time to time in medical circles that one can only learn from real patients because simulation is not real and, therefore, not educationally useful. No matter if communication in a clinical interaction may sometimes remain safely on the surface, no matter if a clinician may work his or her way methodically down a checklist and the patient leave with questions unraised, and concerns unrecognized and unaddressed, the consultation is nevertheless considered real.

From the viewpoint of interpersonal communication, however, it is perhaps more useful to think in terms of authenticity . Rated against that benchmark, there may sometimes be more authenticity in a simulation than in the consultation of a busy clinician, lawyer, or businessman, where heavy workload may crowd out opportunities for real connection. In role-play, participants are given time and opportunity to drop other competing demands to pay full attention to the phenomenon of an interaction, to become aware perhaps for the first time of questions, fears, and personal concerns, and to develop the courage and resources to begin to address them.

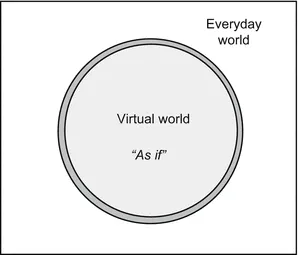

Rather than reality, then, let us in this chapter refer to our usual round of behaviour as everyday life. Whenever we engage in any of these performances, it is as if we draw a circle in the midst of that everyday life and step into it. When we do so, it is almost as if we become someone else. We may find ourselves more confident, more focused, and our senses more heightened. This is the world of performance. Outside the circle lies everything that constitutes our usual behaviour during any given day. Inside the circle, temporarily quarantined from the everyday, is that separate, heightened reality of performance.

Researchers in drama, drama therapy, and psychodrama have come up with various terms to try to define this different reality, such as

imaginative reality, dramatic reality, surplus reality, playspace, fantastic reality, fictional present, liminal field, potential space, aesthetic space, possible world or hypothetical space (Pendzik

2006, 271–280). The different names reflect the differing purposes to which performance can be put. Whatever the term used, each experience of performance is a kind of virtual world, real but not real, a domain that is “both actual and hypothetical: it is the establishment of a world within a world.” In this book, I will refer to this heightened reality of performance as a

virtual world (see Fig.

1.1).

Stanislavsky , the father of modern acting, called this imaginative reality an as if world. The players act as if the situation were that of the real world. In all performance, we play it for real, as if for that moment nothing else in the world existed. Our decisions and actions become of paramount importance, and this concentration of attention releases a focus and an energy that enables superior performance.

The Inner Tension of a Virtual World

The world of role-play, as of much performance, is characterized by unresolved inner conflict. Ambiguity over whether a virtual world is real or not is intrinsic to the nature of role-play as it is to any other form of performance. On the one hand, the interaction is not real, in the sense that it is an unashamed fiction, fiction in the sense of something that is fashioned for the purpose of heightening or shedding light on our everyday behaviour.1 On the other hand, we recognize the behaviour that takes place within this virtual world as actual. The audience knows that they are watching, and the players that they are performing, a fiction, but we agree to act as if it were actually happening. When done well, it is virtually impossible to tell the difference. For all practical purposes, the virtual world reflects life in the everyday world.

Coleridge’s overused term suspended disbelief or suspension of disbelief is often trotted out to describe this transaction between performers and audience. Coleridge coined the term to explain how his contemporary audience, who no longer believed in ghosts and supernatural forces, would accept them in his poetry as if real (Coleridge 1817). The concept has since expanded to describe the convention by which we knowingly suspend our knowledge that we are watching a fiction and choose to accept it as real.

This inner tension is integral and necessary to any virtual world, and its presence is critical if we are to enjoy the experience and learn from it. It enables us to live out experiences that in real life might paralyse us and make us unable to act. For instance, in a virtual role-play world, a trainee police officer may find himself faced with a gun aimed at his chest and the task of talking the gun down. The double awareness of being involved but not really creates safety for both the police officer and the audience. We take it as real, and hold our breath. How will he do it? Will he succeed, or will the gun go off and certainly kill him? The same tension holds true if the task were to talk a would-be suicidal person down off the ledge of a hypothetical 20-storey building.

The fact that we do not know what will happen creates suspense , maintains our interest, and holds our attention . The suspense triggers higher levels of energy and awareness than usual. At the same time, we remain aware that we are not really in the danger of that situation. We have willingly stepped into an alternative space where we can temporarily play with the elements in this fiction, yet remain unharmed. The fiction makes us safe. We return to being like small children who delight in being terrified because we know all along that the scary ghost story is only make-believe.

The fiction , in other words, has the significant advantage of divorcing us from real-world concerns. We are thrown into the middle of the experience, but at the same time we are protected from unpleasant and even dire consequences. This intrinsic tension between the actual and the hypothetical in the virtual world is critical to an understanding of role-play. The unresolved tension acts like a coiled spring within the interaction and produces the energy of suspense , engagement , and enhanced awareness . In successful role-play, it holds us enthralled as we watch to see what will happen and drives the participants and audience towards discovery and new insights.

There needs to be sufficient interest, of course, to provide a riveting focus for attention. The viewers need to be interested, and the action needs to be interesting. Receptive viewer plus interesting action creates satisfying performance. Take away the suspense , the unknown outcome, and heightened focus, and we are left with a cool, intellectual exercise. Without suspense, we can take it or leave it. We watch dispassionately from afar, but we do not experience the almost irresistible pull to forget everything else and pay close attention.

The Frame

Because

our mind is being tugged simultaneously in opposite directions, the two realities of the actual and the hypothetical need to be acknowledged, and to be separated formally from each other. This separation is enabled by the device of a

frame (see Fig.

1.2).

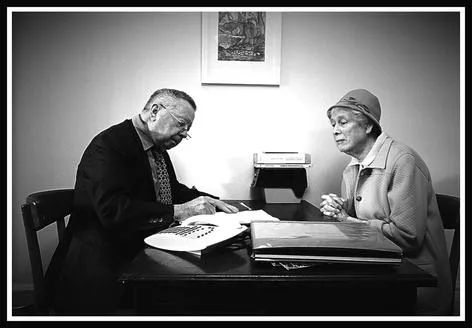

This staged photograph represents a frozen moment in an interaction between two people. We could be looking at a businessman and client, or a clinician and patient. Both parties are focused on their own particular agenda, each more aware of their own preoccupations than of the other. The sheer act of capturing the moment in a still photograph already separates it from the seamless stream of moving experience that brought these two to this moment. Suddenly, the interaction is available to us in a way that was not possible a moment beforehand. The photograph now exists as an object separate from the interaction from which it was extracted. It comes packaged in a rectangular shape, which being unknown in nature, is already a contrived act and acts as an implicit frame. However, we usually heighten and formalize the separation still further by surrounding the image with an external frame.

The convention of a frame is most recognizable from the world of visual art. Each painting in an art gallery is differentiated from the background wall and from the other paintings by its frame. The function of the frame is to separate out the object, and to focus our attention on it. As our eyes are drawn to the image, we are aware somewhere in our psyches of the tension intrinsic to the exercise. Yet, assuming sufficient interest, at a certain moment we forget the presence of the frame, and we step through it, as it were, into the painting. We move perceptually very close in and begin to see things that were not immediately obvious at first viewing. It is as if this image were the only thing that existed, as if it were really real, and we had stepped into that world.

At the same time, another part of our mind remains aware of the frame and that we are in fact standing in a gallery looking at a painting. Depending on our interest, the day, the surroundings, the moment, the picture, and so on, our attention resides somewhere between total absorption in the world of the picture and the detached recognition of the existence of a framed painting. Our example is from visual art, but this device of the frame is used in all performance. It is a crucial factor in role-play.

Aesthetic Distance

This push-me-pull-you tension of a virtual world may be couched in terms of aesthetic distance. The term was first coined by Edward Bullough in the early twentieth century (1912, 87–117).

Bullough asks us to consider the phenomenon of fog at sea. For a sailor, fog might in most cases be seen as an unpleasant experience—cold, damp, and with dangers to shipping that make fog one of the terrors of the seas. Yet, extract the danger and any need to be on alert, and the fog can almost immediately become a pleasant experience. The same negative attributes take on pleasing aesthetic qualities as we consider fog from a totally different point of view. This transformed view is only possible because of the “insertion of distance,” “by putting the phenomenon, so to speak, out of gear with our practical, actual self; by allowing it to stand outside the context of our personal needs and ends—in short, by looking at it ‘objectively.’” This newly enabled aesthetic view “is not, and cannot be, our normal outlook.” It is precisely this transformation of our ability to perceive that enables heightened and hitherto unavailable insights. In Bullough’s words, “The sudden view of things from their reverse, usually unnoticed, side, comes upon us as a revelation, and such revelations are precisely those of Art. In this general sense, Distance is a factor in all Art.”

Consider again the painting hanging in the gallery in terms of aesthetic distance. A visitor to the gallery will tend to experience aesthetic distance in one of three ways: overdistance, engagement, or underdistance.

If nothing in the painting spikes our interest, we will remain unengaged and detached and see only a framed picture hanging on a wall. In relation to the painting, we are not completely present in the moment. In this case, the viewer is overdistanced, and there is no possibility of fresh insight or personal transformation. In Bullough’s example, we see only the usual problem of fog.

Alternatively, the painting may capture our attention. We step through the frame and become caught up in the aesthetic world. We forget time and all other practical considerations and see only this new world within the frame. All we are now aware of is an unexpected experience of fog, as if we had never seen it before. This heightened experience is aesthetic distance at work. Our...