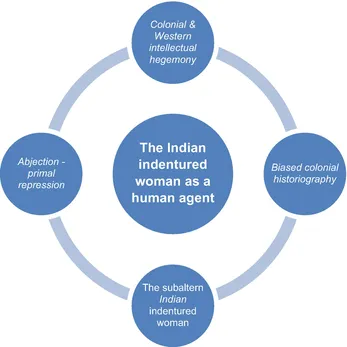

Figure

1 illustrates the theoretical linkages and the purpose of this anthology. Both the theoretical linkages and purpose show that an unbiased history will present the image of Indian indentured women as subalterns who did speak, who experienced abjection and primal repression and also who suffered from gender, race, and class prejudices. At the same time, the planters intentionally perceived these females as subalterns who did not speak, with no capacity to change their circumstances in the face of domination and social degradation, But contemporaneously, Indian indentured women gradually evolved into a human agency.

Social Abjection

The theoretical discussion in this section illustrates how imperialism dominated the British overseas colonies in terms of the ridicule and disgust with which many British colonial officials and planters perceived the Indian indentured population in European-owned overseas plantations (see the chapter “

Devoted Wife/Sensuous Bibi: Colonial Constructions of the Indian Woman, 1860–1900”). Colonial officials and planters regarded their subjects as repulsive and inferior, casting them aside in order to sustain their supposedly superior British identity and social order. Kristeva’s abject psychoanalytic paradigm (

1982, p. 7) describes things and people that are repulsive or disgusting. And so the colonial officials and planters expressed revulsion toward the indentured population through the conceptual tool of social abjection which enabled the planters to sustain their repression, stigmatization, and marginalization of the colonized populations (Mooney

2015, p. 302). Kristeva’s

Power of Horrors (

1982, p. 1) explains abjection thus:

There looms, within abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being, directed against a threat that seems to emanate from an exorbitant outside or inside, ejected beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable, the thinkable. It lies there, quite close, but it cannot be assimilated. It beseeches, worries, and fascinates desire, which, nevertheless, does not let itself be seduced. Apprehensive, desire turns aside; sickened, it rejects.

People who abject show a revulsion toward something that they want to cast aside because of its disruption of their identity or the social order. Moreover, they may want to separate themselves from what they are trying to cast off.

Abject subjects are supposedly alien to the society in which they live, where:

Being made abject constitutes people as “outside the realm of citizenship altogether, constituting them as illegal but … fixing, capturing and paralysing them within the borders of the state” (p. 73). This is a state of being included through exclusion (Mooney 2015, p. 302).

Despite their enduring experience of institutionalized brutality and dehumanization, indentured women responded with protests and other forms of resistance. In fact, throughout this period of colonial domination on the overseas European-owned sugar plantations, Indian women demonstrated a capacity to act and to transform their world with triple oppression: race, gender, and class. Kunti’s story (see the chapter “Kunti’s Cry: Indentured Women on Fiji Plantations”) illustrates this concept. Kunti, an indentured laborer in Fiji, resisted and overpowered an overseer’s sexual advances and eventually returned to India, where the mass-circulation newspapers, the Bharat Mitra and the Allahabad Leader, reported her story. And so the colonized women on the European-owned overseas plantations sparked a passionate campaign, largely by women in India, to end the indenture system. Carter, in Lakshmi’s Legacy (1994), notes women’s resistance and their assertion of their status in colonial society through their absconding, larceny, and violence. Indian women in Guyana ignited protests and contributed to the resistance effort, as their menfolk did; sporadic protests emanated from the weeding gang, which was predominantly the women’s domain; in this context, Salamea, an indentured woman worker, was the ringleader of a major disorder at Plantation Friends in Berbice in 1903 (Guyana National Archives, Governors’ Despatches 190, May 20, 1903 (Colonial Office 111/538)). In 1897, as part of so-called camouflage activism, two Indian women derailed a train at Marienburg in Suriname (see the chapter “Female Indentured Labor in Suriname: For Better or for Worse?”). Between 1886 and 1897, at great risk, Indian indentureds in Fiji brought 622 complaints against their employer (“Murmurs of Dissent” 2012, p. 179). Again in Fiji, Indian women occasionally took the law into their own hands by urinating on cruel overseers (Gill 1970, p. 30). Other cases of women’s role in the resistance effort abound. Interestingly, Indian workers’ resistance transcended gender and thus accelerated the pace of resistance, rapidly limiting the planters’ monopolistic power (GOG 1903).

While Carter points out that women suffered from triple oppression (state, plantation, and family), Anderson (1995), in her review, notes that women had the capacity to negotiate their way through colonial tyranny. As subaltern women, they had a voice to transform their circumstances—that is, they acted as an agency. But how much influence did this agency have? These women needed their own discourse to communicate their knowledge and voice their positions, in order to sustain a viable agency position; largely since, in Spivak’s language (1992), the subalterns’ (Indian indentured women) discourse was quite different from the hegemonic discourse (referring to the discourse of the colonial British officials and planters), it was important that the two discourses did not mix in the dissemination of the subalterns’ message. Any mixture would have resulted in a dilution of the subalterns’ message (Nieuwenhuys and Báez, 2012). And so it was important that the female indentureds presented their message using their own ways of knowing and forms of knowledge, in order to transmit effectively their predicament to the outside world. For this reason, in using their own ways of knowing and forms of knowledge, the Indian subaltern women did speak (Spivak 1992), and voiced their experiences of social degradation.

The Indian Woman as the Subaltern

The Western and sub-Western intellectual elite still has a huge influence on the unrepresentativeness of colonial historiography on Indian women. It is predictable that this historiography largely portrays Indian women’s domination as a civilizing mission , offers a fabricated account of their repression, and projects a biased understanding of their status in the vastly unequal world of colonial India and European-owned overseas plantations. This unrepresentativeness is not surprising given that, generally speaking, Western discourse has an inadequate capacity to connect with non-Western cultures (Spivak 1992). In fact, Spivak argues that since European discourse presupposes that it has knowledge of the “Other” (the Indian woman is the “Other”) as well as the ability to position that “Other” in the storyline of the oppressed, then those Western “intellectuals must attempt to disclose and know the discourse of society’s Other” (1992, p. 66). Spivak uses the term “subaltern” for “Other.” “Subaltern,” Spivak contends, does not constitute “just a classy word for oppressed, for Other, for somebody who’s not getting a piece of the pie” (Kilburn 2012). In this volume, the colonized and gendered Indian woman is the subaltern who constantly faced the wrath of biased colonial historiography.

The Western intellectual elite frequently presumes to be righteous in the amphitheater of colonialism, as it presents the impression of emasculating Western modes of analysis and perspectives, in order to address the oppressed colonial victims (Indian women). But this depiction may be illusory, since there is a huge desire to preserve and implement the elite’s own thinking in its interactions with the colonized, thus:

The theory of pluralized “subject-effects” gives an illusion of undermining subjective sovereignty while often providing a cover for this subject of knowledge. Although the history of Europe as Subject is narrativized by the law, political economy and ideology of the West, this concealed Subject pretends it has “no geo-political determinations.” (Spivak 1992, p. 66).

Further,

Spivak has relentlessly questioned the ability of western theoretical models of political resistance and social change to adequately represent the histories and of the disenfranchised in India. More specifically, Spivak has argued that the everyday lives of many “Third World” women are so complex and so unsystematic that they cannot be known or represented in any straightforward way by the vocabularies of western critical theory (Morton 2003, p. 7).

Again, the nineteenth-century European views of migrant understanding perceived women on the colonial plantations as unwilling, gullible, demoralized, and depraved (Carter 1994).

The penetrative intensity of Western thought as it interfaces with the “third world woman” results in a historical scholarship that refuses to recognize the colonized female, albeit a new female with new characteristics that is alien to the developing world. Spivak (2010, 21–78) characterizes this new female thus:

Between patriarchy and imperialism, subject-constitution and object-formation, the figure of the woman disappears, not into a pristine nothingness, but into a violent shuttling which is the displaced figuration of the “third-world woman” caught between tradition and modernization…

Colonial historiography offers findings on the colonized females from the “Third World”, but in reality those findings have greater relevance for the woman in the developed world.

Spivak’s critique of the Western-biased colonial historiography finds support within Said’s work on Orientalism, where he reflected on Western domination of non-Western countries with the mission to control them. Thus:

What I do argue also is that there is a difference between knowledge of other peoples and other times that is the result of understanding, compassion, careful study, and analysis for their own sakes, and on the other hand knowledge—if that is what it is—that is part of an overall campaign of self-affirmation, belligerency, and outright war. There is, after all, a profound difference between the will to understand for purposes of coexistence and humanistic enlargement of horizons, and the will to dominate for the purposes of control and external enlargement of horizons, and the will to dominate for the purposes of control and external dominion. (Said, E. 2003. “Preface to the twenty-fifth anniversary edition.” Orientalism. New York: Penguin)

Clearly then, in documenting the plight of the subaltern Indian women, there are challenges to the writing of this history to which Spivak (

1992) and Said (

2003) alluded. Furthermore, consistent with Spivak’s and Said’s concerns on the biased colonial historiography, Bhabha (

1994) also advocates a displacement of Western intellectual culture from the postcolonial and colonial frame of reference. And so, in addressing the challenges of a Western-biased colonial historiography:

can be subjected to a translation,...