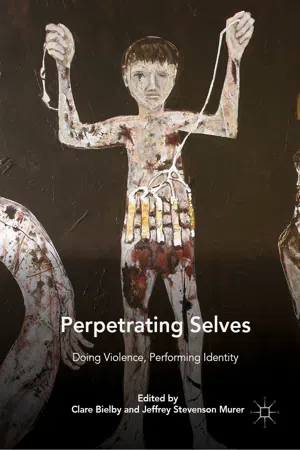

The cover image of this book is the painting ‘The Unbearable Lightness of Being’ (2009) by Steve Pratt, a former SAS soldier and now art psychotherapist and artist whom we interview in this volume. Holding up what looks to be a sort of suicide belt, the figure appears to represent a perpetrating male subject. At the same time, the raised arms gesture towards an act of surrender, whilst the blood around the groin, waist and thighs suggest that the figure might also be a victim of (sexual?) violence, perhaps even pointing to the ‘emasculating’ act of castration, which places the figure in tension with more typical constructions of violence as a hypermasculine force. Meanwhile, the figure’s posture and the way in which he gazes back at the viewer seem to indicate a self-conscious performance, as though he were performing violence (or victimhood) for an audience; he is certainly aware of that audience, whose gaze, if we understand perpetration to be ‘in the eye of the beholder,’ 1 arguably interpellates or constitutes him as a perpetrator (or not).

The image is—in part at least—a self-representation. Pratt suffered what he calls ‘a kind of mental health breakdown,’ which included violent fantasies of perpetration, after he returned from his final tour as an SAS soldier. 2 Painting this image, it would seem, was a way for him to interrogate the self and to work through his ‘perpetrator’ past and the fear that induced. 3 But what form of perpetration is being referenced here? The violent fantasies?; time spent as an SAS soldier?; both of these (and more)?

The image, and our reading of it, raise interesting questions for the present volume, which emerges from a conference that took place at the University of Hull, UK, in September 2015. 4 Firstly, the idea that what counts as perpetration, like terrorism, is always culturally and historically contingent and, to some degree, subjective. Just because violence may be state-endorsed (such as that perpetrated by the SAS) does not mean it cannot count as perpetration—for example, if one has a different moral and/or political outlook to that of the state; if one is operating in a different national/cultural framework; and/or if one is living at a different moment in history. In the present volume, which interrogates examples of perpetration as diverse as National Socialist violence in museums (Luhmann and Meyer), post-terrorist life writing (Bielby), literary representations of the Genocide in Rwanda (Hitchcott) and sexual violence in a contemporary music video (Dearey), we get around the problem of contingency by suspending the legal and moral framework. Anyone who ‘does’ violence is a potential perpetrator—for our purposes at least—and their acts of violence must be read carefully in the context in which they were committed, with reflexivity on the part of the author, as Robyn Bloch’s chapter demonstrates, a particularly useful methodological approach since it helps to mitigate the contingency of one’s own cultural and historical moment and subjective biases. 5

Violence is an equally slippery category. And there is a danger that in focusing on acts of violence and their perpetrators, we might reify those acts and those violent subjects. This can feed into what Rob Nixon has diagnosed as contemporary culture’s preoccupation with ever more ‘spectacular, immediately sensational, and instantly hyper-visible images of what constitutes a violent threat,’ particularly in the post 9/11 world. The result of this, according to Nixon, is that we become less able and willing to apprehend those other—and what he terms ‘slow’—forms of violence; violence ‘that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence.’ 6 In this volume, our contributors seek to situate acts of violence in the contexts of other, less obvious forms of violence, such as structural and symbolic violence (Metcalf) 7 and state violence that is not understood as violence because it is heroised (Koureas). We also seek to avert the danger of reification by regarding perpetration as a form of ‘doing’ rather than something that one ‘is’ (‘the perpetrator’). And as something we might ‘do’ or ‘perform’ as part of ‘doing’ or ‘performing’ our identities more generally. This explains our choice of title: ‘perpetrating,’ as present participle, and reference to the ‘doing’ of violence both point to process rather than essence, whilst reference to ‘performing identity’ makes explicit how ‘doing’ violence is always also part of ‘doing’ our identities. That makes violence, amongst other things, a generative force.

A focus on process points also to post-structuralist conceptions of the self—as fluid, multiple, relational and dynamic. It also raises questions of temporality. If perpetrating is a process and if the self is multiple and fluid, changing over time, what forms of self precede, follow and exist alongside the perpetrating self? The cover image represents a snapshot, which could capture the moment before a horrific act of violence, though it is possible that an act of violence has already occurred, perpetrated against the male figure. Is perpetration, then, the defining aspect for this self, and what are the ethical implications of saying that this is not the case? What about victimhood in relation to perpetration? As Nicki Hitchcott’s chapter so convincingly demonstrates, perpetrating and being a victim of acts of violence in the context of Rwanda were not mutually exclusive. Further, how does re-presenting or re-performing (fantasised) acts of perpetration, as would seem to be the case with Pratt’s image, reconfigure or transform the self? Temporality, and how that affects constructions of the perpetrating self, is a recurring theme throughout this volume (see the interviews with Pratt and John Tsukayama in particular). So, too, is the (ideological and therapeutic) work that repeating, re-performing and re-presenting acts of perpetration might do (on that see Metcalf, Bielby and Birkedal; see also the interview with Pratt). Is there a form of perpetration in the repetition of an act of violence—in linguistic, artistic and/or bodily form? Or is the repetition better understood as a form of working through? Beyond exploring the doing of acts of violence themselves, this volume also interrogates repetitions, re-presentations, reverberations and receptions of violent perpetration in various contexts.

‘Doing’ is always gendered; representing, perpetuating and/or reworking gendered expectations in distinct cultural and historical contexts. Gender is moreover constitutive of how we think about violence, the perpetrator and perpetration. Even etymologically gender, and more specifically masculinity, is written into the category ‘perpetrator’: ‘“[T]o perpetrate” derives from the Latin “per” (completely) and “patrare” (to carry out/bring into existence) from “pater” (father).’ 8 Meanwhile violence is often regarded as constitutive of doing masculinity. 9 No doubt because masculinity and violence so often mutually constitute each other, masculinity has tended to be ignored in discussions of so-called political violence and perpetration, functioning—as so often—as the unmarked gender. 10 Against that backdrop, this volume seeks to make visible the manifold connections between violence and masculinity, as masculinity intersects with other identity categories such as race, ethnicity, sexuality and class (see in particular Bielby and Metcalf; see also Meyer, Koureas and Hitchcott). This does not mean that we focus only on violent masculinities: Bloch’s chapter addresses the memoir of apartheid perpetrator Olivia Forsyth; Melissa Dearey’s chapter explores the representation of young girls as perpetrators in popular cultural discourses on sex crimes; Susanne Luhmann interrogates the exhibition on women concentration camp guards at Ravensbrück concentration camp memorial site. Gender—including in some cases gender queerness (see the Pratt interview and Birkedal’s chapter)—is woven throughout this volume. Gender furthermore is treated not only as an empirical, but also as an analytical category (see in particular Luhmann, Meyer and Bielby). Following V. Spike Peterson, we understand gender analysis to be ‘neither just about women, nor about the addition of women to male-stream constructions’; rather ‘it is about transforming ways of being and knowing.’ 11 Knowledge around violence and perpetration, like all forms of knowledge, is gendered. And what counts as ‘political violence,’ which the emergent field of perpetrator studies seems particularly interested in, is equally gendered. We should be cautious of the word ‘political’ and the politics of representation at stake in using such terminology. As the so-called second-wave feminist movement reminds us, ‘the personal is political.’ And as feminist international relations scholar Laura Sjoberg has argued with regard to mainstream constructions of ‘terror,’ what tends to be understood as ‘political violence’ ‘is often represented as the product of the fears and problems of a small (often masculine [and white]) elite part of the population.’ 12 Sensitive to the contingency and gendered nature of constructions such as ‘political violence’ and ‘political perpetration,’ then, we are intentionally broad in the types of violence we address in this volume. Beyond more typical examples of ‘political violence,’ the volume includes chapters that address so-called ‘personal violence,’ such as prison violence (Metcalf) and sexual violence (Dearey).

As the launch of the ‘Perpetrator Studies Network’ (in 2015), the Journal of Perpetrator Research and the forthcoming Routledge Handbook of Perpetrator Studies suggest, 13 perpetrator studies has emerged as a distinct and self-conscious field of enquiry in the last few years, though its roots go back much further than that, most obviously to the historiography of National Socialism of the 1990s. Perpetrator studies today, as demonstrated by the present volume, is an interdisciplinary field, which is motivated by the idea that if we want to better understand how and why acts of violence take place, we need to address the perpetrator of those acts of violence. We need furthermore to treat that perpetrator as a social being and fellow human, rather than as an inscrutable monster. As Birga Meyer’s and Hitchcott’s chapters and the interview with Tsukayama so eloquently demonstrate, daring to apprehend the human in the perpetrating subject, and treating that subject with empathy is highly fruitful and can help us to reflect upon our own subject positions in instructive ways. Empathy, though, as Bloch’s chapter suggests, can be complex: it does not have to mean experiencing positive emotions. In empathising with her perpetrating subject—apartheid perpetrator Olivia Forsyth—what Bloch felt was more like hate, although that empathic engagement was no less productive for Bloch as the reader of Forsyth’s memoir. As well as focusing on the perpetrating self, this volume is interested in the self that encounters perpetration—as a reader, a museum visitor, a consumer of popular culture, a scholar—and how that self might be shaped by the encounter.

The present volume addresses multiple contexts and forms of violence from a gendered, multi- and often inter-disciplinary perspective, and by means of interrogating a wide variety of texts and sources. The book is organised in three sections: ‘Enactments and Bodily Performances’; ‘Narration and Textual Performances’ and ‘Perpetration in the Museum,’ each of which includes academic chapters and an interview with a practitioner/practitioners. The first section addresses the doing of violence and perpetration as a (bodily) performance, both in a theatrical sense—where there is a clear sense of an actor behind the performance—but also in the context of performing or enacting violence as part of performing one’s identity more broadly, and hence in a performative way. The second section turns to narrative, looking at its role in both making acts of perpetration possible to begin with (how we story the self), but also as a way to retrospectively reflect on, justify and/or come to terms with the perpetration of violence, both on the part of (post-)perpetrators and society more generally. The final section turns to museum representation, addressing the potential and limitations of this institutionalised form of representation of perpetration. The interviews with practitioners bring a distinct and collaborative voice to the mix: the interviews were conducted over a couple of hours and took the form of a discussion between the interviewee/s and the volume’s editors. 14

In the opening chapter, ‘Leading Men a Merry Dance?: Girls as Sex Crime Perpetrators in Contemporary Pop Culture and Media,’ Melissa Dearey explores the controversial dance performance in the music video for ‘Elastic Heart’ 15 (2015) by Australian pop singer Sia. Dearey homes in on the representation of sex crime perpetration and the video’s ambiguity with regard to where perpetrator agency lies, before situating this representation in the wider context of contemporary (pop) culture and public debates around, and perceptions of, child sexual abuse. Dearey’s innovative interdisciplinary methodology combines approaches from cultural criminology with those from dance and movement studies. Amongst other things, the chapter reveals how interdisciplinary methodologies can enrich analyses of gendered perpetrator subjectivities, not least through foregrounding the performing body as a potential source of knowledge.

Like Dearey, Katerina H. S. Birkedal in her chapter ‘Embodying a Perpetrator: Myths, Monsters and Magic’ explores...