- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Children and Borders

About this book

This collection brings together an interdisciplinary pool of scholars to explore the relationship between children and borders with richly-documented ethnographic studies from around the world. The book provides a penetrating account of how borders affect children's lives and how children play a constitutive role in the social life of borders.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Children and Borderlands

1

Experiencing the State and Negotiating Belonging in Zomia: Pa Koh and Bru-Van Kieu Ethnic Minority Youth in a Lao-Vietnamese Borderland

Trần Thị Hà Lan and Roy Huijsmans

Border? It is just the landmark milestone and the Xepone River. A real border does not exist here, at least not for us – we don’t see it. (Male youth, Lao side of the border)

Introduction: nation, state, and Zomia

Geopolitical borders physically demarcate the nation-state. They delimit the territoriality of nations, which Anderson (2006) famously described as ‘imagined communities’. It is the work of states to construct and nurture such imagined communities, first and foremost within its national borders. This is done, among other things, through projects of nationalism which are here understood as efforts ‘to make the political unit, the state (or polity) congruent with the cultural unit, the nation’ (Fox and Miller-Idriss, 2008, p. 536). Such social practices or the absence thereof erect borders but also render borders irrelevant, rather than the physical demarcation of state territory as the quote above illustrates.

Historians of childhood and youth have long argued that state efforts to construct national identities as part and parcel of the project of nationalism, often take distinct generational forms. Examples include state-regulated mass-education (Cunningham, 1995) and mass-movements such as boy-scouts and girl-guides (see, e.g., Mills, 2012). Similar to projects of nationalism in the western world, such state practices were key in former socialist contexts in the making of the ‘socialist man’ (see, e.g., Avis, 1987). In the contemporary post-socialist states of Southeast Asia these practices have remained important for constructing and nurturing the idea of the nation (Evans, 1998; Marr and Rosen, 1998; Nguyen, 2006; Salomon and Vu Doan Kêt, 2009).

In the context of contemporary Southeast Asia, many states may have roots going back to ancient monarchies or empires yet, ‘the nation-state as a dominant political form is quite recent and is often still in the process of formation’ (Castles, 2004, p. 16). The Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos) and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (Vietnam) are young, multi-ethnic states that still bear the scars of recent internal conflicts. In such a context, forging a degree of cultural unity is no easy task, despite the political importance attached to this by the ruling communist parties of the Laos and Vietnam. Scott’s (2009) work suggests that efforts of constructing the nation will be particularly contested in the mountainous parts of Southeast Asia that Van Schendel (2002) has termed Zomia where ethnic minority populations straddle geopolitical borders.1 Scott argues that Zomia has historically been a zone of refuge where every dimension of social life could be read as a ‘strategic positioning designed to keep the [lowland and ethnic majority] state at arm’s length’ (Scott, 2009, p. x).

This chapter is based on research conducted in four ethnic minority villages in a Lao-Vietnamese borderland area located on the Savannakhet (Laos) – Quang Tri (Vietnam) border. This upland, ethnic minority populated area is a part of the region termed Zomia. Given the historical ambiguity of the state in Zomia, the borderland’s physical remoteness from the respective state centres, and the key importance of young people in the project of constructing the nation in this post-socialist context, we focus in this chapter on young people’s experiences and perceptions of the state and their positioning vis-à-vis the nation in their everyday lives in this borderland area.

By doing so, we contribute a generational perspective to the growing body of work on the ethnography of borderlands in Southeast Asia (Walker, 1999; Kalir et al., 2012; Eilenberg, 2012). Unlike elsewhere ( Hipfl et al., 2003; Christou and Spyrou, 2012; Smith, 2013), the Southeast Asian literature, thus far, has remained adult-centric in focus. This is evident, for example, from Eilenberg’s (2012, p. 4, emphasis added) otherwise compelling description of borderlands as ‘laboratories for understanding how citizens relate to ‘their’ nation-state and how competing loyalties and multiple identities are managed on a daily basis’.

Situating research sites, methods and subjects

For this study, we adopted a cross-border approach conducting research in four ethnic minority villages; two located on the Lao side of the border (one Pa Koh and one Bru-Van Kieu) and two on the Vietnamese side of the border (also one Pa Koh and one Bru-Van Kieu). Pa Koh and Bru-Van Kieu are two groups of Mon-Khmer speaking peoples (the various Mon-Khmer languages make up one branch of the Austroasiatic family of languages) residing on both sides of the Lao-Vietnamese border (Pholsena, 2008). Pa Koh and Bru-Van Kieu peoples differ considerably from the dominant (lowland) populations in Laos and Vietnam, the ethnic Lao and Kinh respectively, in terms of cultural practices and language, socio-economic profile and political power.

Economically, agriculture and collection of forest produce are the main sources of livelihood in the research villages. Agriculture is mostly for own consumption but has increasingly been directed to the market (especially the production of cassava root). Opportunities for earning cash for young ethnic minority villagers are limited. At the same time, the lifeworlds of these young people are rapidly being monetized. Like their peers in lowland areas, they are interested in fashion, mobile phones, exploring the internet and spending time playing pool and other forms of leisure that usually don’t come for free. Young people are actively involved in many types of work in their households and family fields but this is generally unpaid labour. In such a context, trafficking in wood and wildlife across the Lao border into Vietnam offers an important source of income for youth in particular.

On the Vietnamese side of the border, the remaining forests have been largely stripped from their valuable resources, which are in high demand in the populous lowland areas of Vietnam and beyond. This is still not the case on the Lao side. Kinh traders, thus, have shifted their catchment areas to include the forests on the Lao side of the border. Ethnic minority youth are important actors in the trade. They know the forest, they can draw on ethnic networks that stretch across the border, and they possess the strength to carry out this physically taxing work. Moreover, these young people are mostly out-of-school and do not have their own fields to attend or their own independent households to look after.2 Youth are thus, more so than adult villagers, in a position to spend a day, or sometimes longer, in the forests hunting for valuable woods or animal species.

This practice is usefully understood with reference to the distinction between the realm of state authority, rendering practices legal and illegal, and social regulation, rendering practices licit and illicit (see Kalir et al., 2012, p. 19). Cross-border trade in precious wood and wildlife species is forbidden by the concerned states; yet, socially sanctioned in these borderland communities. Both young men and young women are involved in the practice. However, their participation is shaped by relations of gender and nationality. Young women do not typically get involved in overnight expeditions and are considered too weak to ride motorbikes with logs weighing up to 200 kg. Such long-distance and motorized logging or wildlife hunting trips are obviously more risky, but also more profitable. The main roles of young women involved in the trade are mostly limited to looking for valuable forest produce on foot in the relative proximity of the villages and to porting of smaller pieces of wood on their back – which are still very heavy! It should further be added that only young women from the Vietnamese side of the border are involved in the wood trade. We did not find young women from the Lao side of the border involved in the wood trade, but only in the collection of non-timber forest produce.

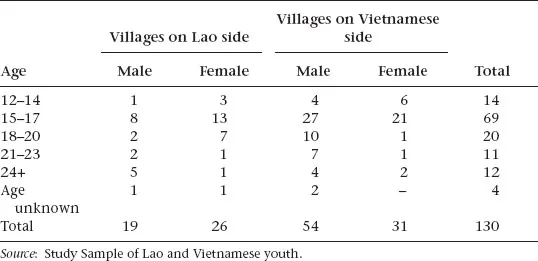

The fieldwork on which this chapter is based was conducted in 2011–2012 by the first author and constituted a mixed-methods approach carried out within an overall ethnographic research orientation. Methods included survey research among a total of 130 young people (see Table 1.1). Some of these young people were subsequently selected for semi-structured individual interviews, group activities and informal group discussions. Although the main focus was on youth (both young men and women), adults and older people also participated in the research where appropriate (for a full methodological discussion see Trần Thị Hà Lan, 2011). Research was conducted in Pa Koh and Bru-Van Kieu ethnic minority languages and Vietnamese where appropriate.3 For the former, the first author worked with two research assistants from the communities. Working with local research assistants and employing vernacular languages was, next to pragmatic reasons, also done in order to give greater voice to ethnic minority youth.

Table 1.1 Youth in the study sample (n = 130)

From the perspective of the respective states, the ethnic minority borderland in which the study was conducted is considered a sensitive area. It is only because the first author has long worked as a development practitioner in this area, that the request for conducting field work was met with approval by local and district authorities. All young respondents and their parents were informed about the nature of the study at the start of the research, as well as at later stages in the research (e.g. when conducting group activities) to ensure that consent was informed and maintained. Consent (both for the use of interview material and art work in academic publications) was obtained orally, which we believe is more appropriate in a context in which signing forms is associated with practices of an authoritarian state. In order to protect the identity of the respondents we refrain from naming the research villages and the respondents.

All young people participating in the research were unmarried. Where known, we have indicated the age and gender of the respondents in presenting quotes. For quotes from spontaneous group discussions, which were at times mixed-gender, this was not always possible. Out of the total sample the vast majority (70 per cent) was out-of-school and most would associate themselves with the identity construct of ‘youth’, which they understood as:

Youth is the period in between. We don’t belong here or there. We have no complex thinking, we like many things, there is no pressure. (Male youth, Vietnamese side of the border)

Youth in this context is only partly determined by chronological age and essentially a relational construct referring to those young people who are not children anymore, yet, are also not yet considered adults. In describing the meaning of youth, young people themselves would further stress the performance of the cultural style of being young as an important characteristic of youth. This is expressed by, for example, the language one uses, dress and hairstyles one wears, being mobile phone literate, and listening to the ‘right’ music. Young people would further emphasize a sense of ‘freedom’ as an element of what defines youth; being relatively ‘free’ from the responsibilities that they associate with adulthood. This relational and performative understanding of youth means, indeed, that for some, and especially for some young women who marry early, youth may not last longer than a few years (if at all):

Youth is totally over when we get married, we start a dependent life with our husband’s family, follow traditional practice and are not youth anymore. (Female youth in group discussion, Lao side of the border)

State, nation and belonging on the Lao-Vietnamese border

Although located on the very edges of state territory, the four study villages have long experienced the presence of states. This is perhaps most dramatically illustrated with reference to the cross-border population movements during and in the aftermath of the Second Indochinese War (1954–1979).4 The four villages have relocated due to these geopolitical developments and the coordinates of the Lao-Vietnamese border have also changed. The two Bru-Van Kieu villages originate from both sides of the current Lao-Vietnamese border. During the war the villagers had moved across the Xepone River and further inland into Laos. After the war, part of this population returned to their original site on the Lao side of the border, while others established a new village across the Xepone River on Vietnamese territory, near the original site. The populations of the two Pa Koh villages both originate from the Lao side of the border. However, they come from further afield, namely from the mountainous area of Samouay district of Salavanh province (South of Savannakhet province, also bordering Vietnam). After the War, these Pa Koh populations wanted to be ‘closer to the Vietnamese government’ according to older villagers and established the current village on Vietnamese soil. However, a part of this population was not allowed to settle across the border and, therefore, established their village right on the Lao side of the border.

The Pa Koh and Bru-Van Kieu populations were actively involved in the Second Indochinese War and generally sided with the revolutionary Vietminh. This historical relation with the current administrative powers is still evident today. Medals and awards are prominently displayed in the houses alongside posters of Ho Chi Minh and less commonly the former Lao president and revolutionary hero, Kaysone. In addition, villagers have adopted the surname ‘Ho’ (of Ho Chi Minh). This surname is still carried officially, next to their own family surnames, by villagers on the Vietnamese side of the border. On the Lao side, the current generation no longer carries this name in official records, yet some youth are still familiar with its meaning and practice.

Given the social history of th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I Children and Borderlands

- Part II Children, Borders and War

- Part III Children and Contested Borders

- Part IV Children Crossing Borders

- Part V Children, Borders and Belonging

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Children and Borders by S. Spyrou, M. Christou, S. Spyrou,M. Christou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Early Childhood Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.