eBook - ePub

The Public Financiers

Ricardo, George, Clark, Ramsey, Mirrlees, Vickrey, Wicksell, Musgrave, Buchanan, Tiebout, and Stiglitz

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Public Financiers

Ricardo, George, Clark, Ramsey, Mirrlees, Vickrey, Wicksell, Musgrave, Buchanan, Tiebout, and Stiglitz

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

To follow.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Public Financiers by Colin Read in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section 1

First Forays into Tax Incidence and Public Policy

I begin with the wisdom of David Ricardo and the ways in which he provided material for both sides of a debate that raged between Henry George and John Bates Clark at the end of the 19th century. This great debate started with America’s first populist economics movement, and ended with the embracement of the neoclassical model of economics. An ideological battle has ensued ever since.

1

The Early Life of David Ricardo

David Ricardo was not the first political economist. But he was perhaps the first economist of the modern era. Where those who came before him, most notably Adam Smith (June 16, 1723–July 17, 1790), provided wonderful rhetoric with great flourishes of their pen, Ricardo was the first to convert intuition to a language that was amenable to mathematics and graphs. He also produced concepts that are still taught today – in almost precisely the same form as he had employed in his original pre-sentations. While many have since attributed his ideas to other Great Minds such as Paul Samuelson (May 15, 1915–December 13, 2009), we can see so many roots of modern economics and public finance from his writings almost two centuries ago.

Once we understand his pedigree, perhaps his accomplishments appear at the same time all the more remarkable and predictable. For his story actually begins well before he is born. It is a story that overlaps with that of Franco Modigliani (June 18, 1918–September 25, 2004), who was to win the fourth Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences more than a century after Ricardo’s death.

While Ricardo was born in London, his family had taken a circuitous route before arriving in the United Kingdom. His ancestors date back to before their expulsion as Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal in 1492. (The term Sephardic is derived from the Hebrew word for the nation of Spain.) Their expulsion occurred in the same year as Spain’s Queen Isabella ordered Christopher Columbus and his ships, the Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria, to set sail on their voyage of exploration for the New World. As many as one-third of the crew of Columbus’ ships were Jews. Other Sephardic Jews scattered across the Mediterranean Sea to other points in Europe.1 Over generations, some remained in Spain and were forced to make a public conversion to Christianity, while continuing to practice their Judaism in private. Some of these Marrano Jews eventually made their way from Spain to Amsterdam, a trade-oriented city known, even in the 16th and 17th centuries, for its religious tolerance. Some did so by way of Livorno, Italy, across the Mediterranean, where a healthy Jewish community had lived for some time.

By the mid-18th century, the Ricardo family had migrated from Spain via Livorno in Italy, and they had subsequently established themselves in Amsterdam. Other Sephardic Jews were to remain in Livorno. From these ancestors came Amedeo Modigliani (July 12, 1884–January 24, 1920), the great 19th- and 20th-century sculptor and artist, and his cousin, the Great Mind Franco Modigliani (June 18, 1918–September 25, 2003), who was to be awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1985.

Joseph Israel Ricardo, the grandfather of David Ricardo, was a stockbroker and leading figure at the Amsterdam Bourse. He and his family enjoyed a comfortable living. Joseph had many children, first as a product of his marriage to Hannah Israel, who died in 1725, four years after their marriage, and as a result of his subsequent marriage to Hannah Abaz (1705–November 19, 1781), whom Joseph married in 1727.

Two daughters and four sons resulted from Joseph’s second marriage. Three of the sons also went on to become stockbrokers, including the youngest son, Abraham Israel Ricardo.

Born in 1733 in Amsterdam, Joseph’s son Abraham first established himself in Holland, but by 1760 he had transplanted himself to London, England to help with the running of his father’s expanding cross-channel business. He and his father had been investing heavily in what the father of political economy, Adam Smith, referred to as the English Funds, fueled by borrowing by England to pay to fund the Seven Years’ War which had first erupted with France in 1756. Holland remained neutral during the war, and over the period it used its neutrality to expand trade significantly with England. Abraham Ricardo represented in London many Dutch interests over these war years.2 He was an active and respected trader on the Stock Exchange of London who, like his father, amassed a considerable wealth.

Nine years after his arrival in London, Abraham met Abigail Delvalle (1753–October 22, 1801), a young woman of 16 years of age – two decades his junior. Abigail was the eldest of eight children born to Abraham Devalle (1726–1785) and Rebecca Henriques de De Sequeira (1737–1787). The Devalles were well-established English merchants and importers, and central figures in the Sephardic Synagogue in London.

Abraham Devalle and Rebecca Henriques de De Sequeira, David Ricardo’s maternal grandparents, had married on September 20, 1751. Less than two years later, Rebecca had given birth to their first daughter, Abigail. Widely regarded as a beautiful child and young woman, Abigail was raised in the Synagogue and became acquainted with Abraham Ricardo not long after Ricardo became established in London’s Jewish community.

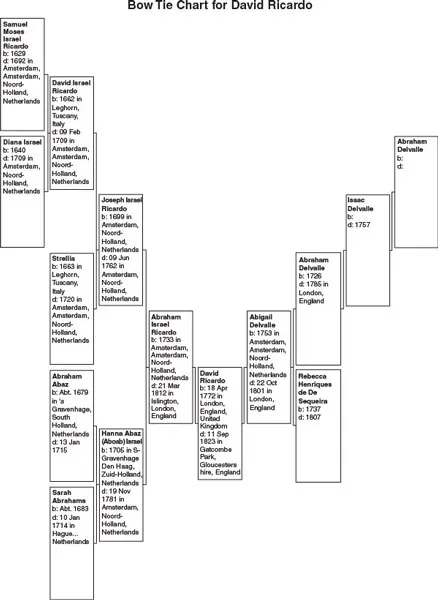

Figure 1.1 Ancestors of David Ricardo

Abraham and the 16-year-old Abigail married on April 30, 1769. Together, they had at least twenty children, of whom six daughters and nine sons reached adulthood, and fully two-thirds of the nine sons followed in the footsteps on their father and grandfather and became stockbrokers.

The third child of Abraham and Abigail, David Ricardo, was born on April 18, 1772, shortly after his parents’ third wedding anniversary. By this time, his family had achieved a modest degree of wealth in the financial and mercantile markets of London, and David grew up in comfortable circumstances, even though he received a common education at the neighborhood school during the lean war years, rather than the private education afforded others of his family’s stature.

When David was a young boy, the family suffered the years of the 4th Anglo-Dutch War that ran from 1780 to 1784. The Dutch had been the prevalent economic power in the 17th century, but Britain grew rapidly in power and influence in the mid- to late 18th century, in equal parts because of its alliance with the Dutch and its prominent role as the engine of the Industrial Revolution. English economic and military ascendancy led to a growing resentment among the Dutch. A Dutch treaty with a recently independent United States increased the tensions between the two former European allies. In an effort to restrict trade with the United States, the British exercised its new-found economic and military clout by attempting to convert the Dutch Republic to a British protectorate. The two nations each diverted considerable resources to achieving a doubling in the size of their respective seafaring fleets at that time, even if, after four years of conflict, the war ended in a stalemate.

Once peace was restored, David Ricardo resumed his education with his father’s relatives who had remained in Amsterdam. While there, David was expected to learn the family financial trade and custom between the two nations, the Dutch language, and Jewish traditions in preparation for his Barmitzvah at the age of 13.

After a few years of religious and formal education in Amsterdam, David returned to his family home on Bury Street in London to continue his apprenticeship in the family business. The family then purchased a new home in Bow, about a mile north of the Thames River, and only a couple of miles from London’s financial district at that time, and much closer to the heart of London.

In their new and prominent neighborhood, the 20-year-old David Ricardo met the eldest daughter of a well-known surgeon, Edward Wilkinson (1728–November 4, 1809), and his wife Elizabeth Patterson. The daughter, Priscilla Ann Wilkinson (November 5, 1768–October 17, 1849), was raised as a Quaker to her devout family. The ensuing courtship and marriage of David Ricardo and Priscilla Ann Wilkinson, on December 20, 1793, was the cause of discord among the Ricardo family over issues of religious faith and David’s break from the Jewish Synagogue and community in London.

The breach of faith between David and his father, instigated by his mother, was not permanent, although it did last until David’s mother died in 1801 – almost a decade after David’s marriage.3 To be fair, however, the Wilkinsons were equally troubled by the youthful exuberance of David and Priscilla, and they also temporarily refused to support the young couple. Fortunately, David was already financially secure, and he did not need to rely on the wealth of his family.

It seems likely that Ricardo’s separation from his faith was not caused entirely by his marriage to Priscilla. Like many intellectuals in that era, David Ricardo had already discovered the Unitarian faith, and he was attracted by both its liberalism and its intellectual leanings. Quakers had dissented from the more hierarchical leanings of the Catholic Church and the Church of England. Those who dissented still further often found themselves embracing Unitarianism. Many religious, philosophical, and economic liberals questioned the dictates of organized religion and embraced the Christian theological movement that asserted God is one entity, in contrast to the Holy Trinity, which defines God as being embodied in The Father, The Son, and The Holy Spirit. Unitarians accepted Jesus as the son of God, but they regarded him as a prophet rather than a god in his own right. Unitarians also rejected original sin and predestination, and permitted the Bible to be read in a metaphorical rather than a literal manner. As a consequence, it was considered one of the most liberal of all Christian churches, and permitted a diversity of interpretation and thought among its followers.

Then, as now, it was not unusual for liberal Christians to attend services with Quakers or Unitarians, as both religions espoused a substantial level of religious tolerance. Indeed, David’s wife continued to attend Quaker gatherings, and she certified the birth of some of her children in the Quaker fellowship. By contrast, David remained uneasy with any religions that were more organized and hierarchical than Unitarianism.

David held considerable sway over the lives of his younger brothers, and many of them were to follow his example and marry out of their Jewish faith. His brother Moses (November 13, 1776–March 7, 1866), for example, married Fanny Wilkinson, one of Priscilla’s younger sisters, and became a partner in surgery with one of Priscilla’s brothers, Josiah Henry Wilkinson. While this generation of Ricardos and Wilkinsons were close and intertwined, the generation did not typically retain close relationships with their respective parents. They had busy careers, cared for large families, and were distracted by many events at the national scale that shaped their lives. One of these, the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, was soon to determine Ricardo’s fortune.

At the end of the 18th century, England was fearful of the prospects for a conflict with France. The French Revolutionary Wars from 1792 to 1803 transitioned into the Napoleonic Wars from 1803 to 1814. Fearing an invasion by Napoleon, militias formed in England, including in the Royal Lambeth Volunteers in the Ricardos’ neighborhood just south of the Thames River and the financial district in London. When the Ricardo family moved farther east in London, to Bromley, David took a commission as Captain in the Bromley and St Leonards Corps on August 17, 1803.4 His brother was the Corps surgeon. He also served with James Mill (April 6, 1773–June 23, 1836), the father of John Stuart Mill (May 20, 1806–May 8, 1873), an economist and the eventual co-founder of classical economics as inspired by David Ricardo.

In Bromley, South London, the Ricardos lived a comfortable, almost rural existence at that time. However, by the spring of 1812, the large Ricardo family, which had grown to include three boys and five girls, moved to an estate in the fashionable West End of the City at 56 Upper Brook Street, off Grosvenor Square. Ricardo commissioned Samuel Pepys Cockerell (1753–1827), the famous English architect who was a great-great nephew, and namesake, of the well-regarded diarist Samuel Pepys (February 23, 1633–May 26, 1703) to remodel his house, which had been built in 1729. This house was to be Ricardo’s home for the rest of his life.

In the year that the Ricardos moved to Grosvenor Square, one of the most influential economists of the day, the Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus (February 13, 1766–December 29, 1834), had joined the King of Clubs, an exclusive club that met in London during this period. Already by this time, Ricardo had been drawn into membership of a scientific society called the Geological Society of London. Successful in business by the time he was in his thirties, Ricardo became a lover and patron of the humanities and sciences societies and, increasingly, this new social science of economics. Ricardo was nominated to the King of Clubs on June 7, 1817, and had helped found the Political Economy Club in April of 1821.5

Ricardo’s fortune

By the early 1820s, David Ricardo had reached the pinnacle of the social, familial, financial, and intellectual circles of London. He did so not through the help of family money but through the exercise of his personal cunning. Years earlier, at the age of 14, upon his return from Amsterdam, David Ricardo’s father had begun to teach David the workings of the London Stock Exchange. Shortly before his marriage in 1793, Ricardo was already listed on the Exchange ledgers for his trading in bonds of the Government of England. When he became estranged from his family later that year, however, colleagues he had come to know at the exchange helped establish him as a broker in his own right. The investment banking firm of Lubbocks and Forster offered him financial backing which he leveraged, in just a few years, to a fortune that exceeded the wealth of his father.

Ricardo was well respected within the London financial community. When two fraud scandals rocked the Stock Exchange, in 1803 and in 1814, the exchange looked to Ricardo for helping in resolving the problems and also the restoration of market confidence.

Ricardo did not act as a broker, however. Rather, he functioned as a jobber – what we would today term a market-maker. He used his own funds to quote prices for securities for sale or to purchase, primarily of bonds issued by the Bank of England or the East India Company. For each pound of securities traded for cash, about ten pounds of trade was done on time, with a promise to settle on one of eight settlement days each year. The jobber was hence both a trader and a banker.

Ricardo’s key insight was his observation that other traders typically “exaggerated the importance of events”.6 Ricardo became a student of human nature and emotion, and he profited from it. He also recognized that markets suffer significant overshooting in their oscillations toward equilibrium. His observations of human nature and trading informed him in ways almost unparalleled among all but some of the profession’s most successful economists, including the Great Minds Irving Fisher (February 27, 1867–April 29, 1947) and John Maynard Keynes (June 5, 1883–April 21, 1946), both of whom also traded actively and professionally. His financial acumen would soon allow him to accrue a vast fortune.

2

The Times

Prior to the theories of Ricardo, the economic landscape had been shaped by Adam Smith’s observations. Ricardo had been first exposed to Adam Smith’s 1776 Wealth of Nations in 1799, when he was in his early twenties. Smith’s writing gave Ricardo a context from which to organize his own observations of the functions of the market. Also, from Smith and Malthus came the notion of the law of natural prices, which Ricardo later repealed.

Ricardo also weighed in on the role of the money supply. In response to the mounting costs for England in their campaigns of the Anglo-French Wars and the Napoleonic Wars, Ricardo observed that the efforts by the Bank of England to suspend the convertibility of bank notes into gold, which was arguably intended to induce inflation, would also reduce the wealth of those who had purchased government bonds. By then, Ricardo was both a large trader and holder in bonds.

Ricardo responded to what he viewed as institutional market manipulation by writing his first article, ‘The Price of Gold’, which he published anonymously in The Morning Chronicle in 1809. He bolstered his non-interventionist argument a year later with his publication of the pamphlet The High Price of Bullion, a Proof of the Depreciation of Bank-Notes. This publication was to be most influential in the government circles in 1810. Over the first decade of the 19th century, Ricardo had become an advocate of a movement called The Bullionists, who argued that a gold standard ensures a s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Series Preface

- Preface to This Volume

- Introduction

- Section 1: First Forays into Tax Incidence and Public Policy

- Section 2: From Burden of Taxation to Optimal Taxation

- Section 3: Divergent Arguments for the Public Sector

- Section 4: Bringing it all Together – Voting with the Feet and the Henry George Theorem

- Section 5: What We Have Learned

- Glossary

- Notes

- Index