eBook - ePub

Missionary Masculinity, 1870-1930

The Norwegian Missionaries in South-East Africa

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

What kind of men were missionaries? What kind of masculinity did they represent, in ideology as well as in practice? Presupposing masculinity to be a cluster of cultural ideas and social practices that change over time and space, and not a stable entity with a natural, inherent meaning, Kristin Fjelde Tjelle seeks to answer such questions.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Missionary Masculinity, 1870-1930 by Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia africana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Historia africana1

Introduction: Missionaries and Masculinities

This book examines male missionaries and constructs of masculinity. A missionary can be defined as someone who attempts to convert others to a particular doctrine, programme or faith. Although it is not always the case, a missionary is often seen as someone ‘going to’ or being ‘sent to’ a ‘foreign’ place to carry out a mission. The group of men scrutinised in the current study served as Christian missionaries between 1870 and 1930, representing the Lutheran mission Norwegian Missionary Society (NMS), which was established in 1842. The first NMS missionaries reached the shores of south-east Africa in 1844, arriving at the coastal town of Durban, which was situated in a region that had been proclaimed the British Colony of Natal in the previous year (1843). The target group for their missionary activity was the Zulu ethnic group.1 In addition to establishing a ‘mission station’2 in Natal, the NMS missionaries also settled in Zululand, a sovereign African kingdom on the eastern frontier of Natal.

What kind of men were these Norwegian Lutheran missionaries? What kind of masculinity did they represent, in ideology as well as in practice? What kind of processes obtained when a missionary masculinity was constructed? Presupposing masculinity to be a cluster of cultural ideas and social practices that change over time (history) and space (culture), and not a stable entity with a natural, inherent and given meaning, this study seeks to answer such questions. First, it examines how a missionary masculinity was constructed in the NMS. Second, it looks at how a missionary masculinity was represented in the Norwegian Lutheran mission discourse. Finally, it explores the practical implications which the construction of a missionary masculinity had for the male missionaries themselves as well as for other groups of men and women participating in the Norwegian–Zulu encounter.

This book suggests that Norwegian Lutheran missionary masculinity was constructed in the tension between modern ideals of male ‘self-making’ and Christian ideals of ‘self-denial’. It was also constructed in the tension between missionary men’s subjectivities as modern professional breadwinners in an enterprise with global interests, and their subjectivities as pre-modern housefathers in an enterprise that expected their private and domestic lives to be integrated into their professional missionary lives. Finally, missionary masculinity was constructed in the tension between powerlessness and power. On the one hand, inappropriate missionary masculinity, or missionary unmanliness, meant powerlessness. This study reveals that not all missionary men lived up to the standard, and the personal costs of ‘falling’ into missionary unmanliness in some cases meant catastrophe and death. On the other hand, however, appropriate missionary masculinity meant powerfulness. The missionary men were originally from humble social backgrounds. Through their engagement in the missionary enterprise they were empowered, moving from being ‘nobody’ to being ‘somebody’. When they encountered African masculinities, settler masculinities and imperial masculinities in south-east African societies, the complexity of Norwegian missionary male subjectivities was further increased, and in the context of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century South Africa, Norwegian missionary masculinity meant power, not powerlessness.

The case and the context: Norwegian missionaries in south-east Africa

The NMS’s mission in nineteenth-century south-east Africa was known in Norway as ‘the Zulu mission’ (Zulu Missionen). From 1844 to 1930, 56 men and 76 women served as labourers in the Norwegian ‘mission field of Zululand and Natal’, an endeavour which from 1910 after the creation of the Union of South Africa from the previous Cape and Natal colonies as well as the Orange Free State and Transvaal republics was defined as ‘the NMS’s mission in South Africa’. Norman Etherington claims in his classic study of missionaries and Christian communities in south-east Africa that no other parts of nineteenth-century Africa were so thickly infested with Christian missionaries as this region.3 Besides the NMS, other bodies working in the field included the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (Congregational and Presbyterian) from 1835, the Church Missionary Society (Anglican) from 1837, the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society from 1841, the Berlin Missionary Society (Lutheran) from 1847, the Oblates of Mary Immaculate (French Roman Catholic) from 1852, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (Anglican) from 1853, the Hermannsburg Missionary Society (Lutheran) from 1854, the Scottish Presbyterian Mission from 1864 and finally the Church of Sweden Mission (Lutheran) from 1876.

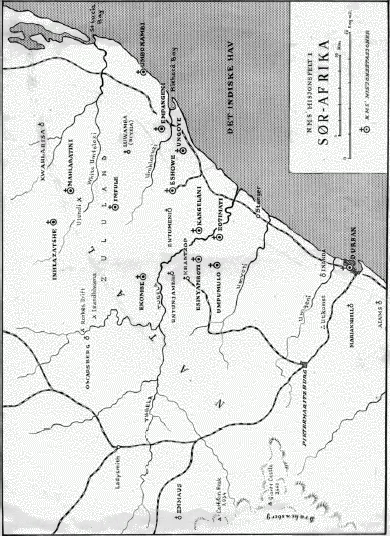

Figure 1.1 A map of the NMS’s ‘missionfield’ in South Africa, printed in the NMS’s organizational history published at the centenary in 1942

Source: Mission Archives, School of Mission and Theology, Stavanger.

With the purchase of Umphumulo Mission Reserve in 1850 the NMS, like the other missions in the region, first settled in the colony of Natal but the Norwegians were eager to get a foothold in the heart of Zululand, and as the first Western missionary the NMS pioneer Hans Paludan Smith Schreuder received King Mpande kaSenzangakhona’s permission in January 1851 to establish permanent mission stations on royal land.4 John William Colenso, the Anglican Bishop of Natal from 1853, was granted the same permission in 1859.5 From 1851 to 1871 nine Norwegian mission stations were established in Zululand at Empangeni (1851), Entumeni (1852), Mahlabatini (1860), Eshowe (1861), Nhlazatsche (1862), Imfule (1865), Umbonambi (1869), Umizinyati (1870) and Kwahlabisa (1871). The Anglo-Zulu war of 1879 resulted in the fall of the independent Zulu state and introduced a colonial system of indirect rule through 13 chiefs under the guidance of a British Resident. The lifespan of the 1879 ‘settlement’ was brief, however. A new division of Zululand in 1883 resulted in the outbreak of civil war, and was followed by British annexation of all of Zululand in May 1887.6 In 1898, effective administrative control of Zululand was transferred from the metropolitan authorities in London to the self-governing settler colony of Natal, which had gained its independence in 1893. The NMS’s mission stations of Umizinyati and Kwahlabisa were ‘lost’ during the time of political turbulence, but land at Ekombe (1880) and Ungoye (1881) was offered as compensation by the new rulers. Later, the NMS also established mission stations at Eotimati (1886), in Durban (1890) and at Kangelani (1915).

There have been some previous studies on the NMS missionaries in south-east Africa. In the early 1970s, the Norwegian historian Jarle Simensen initiated a research project whose aim was to exploit Norwegian missionary material from South Africa and Madagascar in the nineteenth century in order to shed light on local African history. Significant contributions were made by six master’s dissertations covering the African side, three of which concerned South Africa,7 and one covering the Norwegian background of the missionaries.8 The main findings of the project regarding South Africa were presented in 1986 in the edited book Norwegian Missions in African History.9 The introductory part contained an analysis of the geographical, socio-economic, religious and family backgrounds of the nineteenth-century NMS missionaries and concluded that the majority were recruited from farmers and middle-class craftsmen engaged in revivalist movements in the coastal areas of south-western Norway. The main part of the book focused on the political and social interaction between the missionaries and the African people concerned. The book addressed the NMS missionaries’ role directly in relation to the British colonial enterprise and indirectly in relation to the steady incorporation of Zulu society into European forms of modernisation. Simensen’s comprehensive project attracted much attention, not least because it was the first time scholars outside the NMS’s internal circles had examined the political and social role of Norwegian missions in African societies. The project can be regarded as part of a Marxist-oriented, anti-imperialistic tendency in historical research, following the processes of post-colonialism in Africa and Asia.10

Meanwhile, the church historian Torstein Jørgensen’s doctoral thesis Contact and Conflict: Norwegian Missionaries, the Zulu Kingdom and the Gospel 1850–1873 (1990) examined the encounters between the NMS missionaries and the Zulus.11 Although social and political aspects of the encounter were considered in this work as well, Jørgensen’s intention was to emphasise the processes of religious transmission. Given that the Norwegian mission among the Zulus produced few converts in the first three decades, Jørgensen assumes that both ‘contact’ and ‘conflict’ characterised the process. The NMS missionaries’ attitudes towards a rising African nationalistic movement in South Africa in the 1920s, as well as towards the internal independence efforts of Zulu pastors in the Norwegian mission church, were examined in Hanna Mellemsether’s doctoral thesis of 2003.12 Mellemsether finds that close relations with the white settler establishment, which had Norwegian roots, influenced the missionaries’ standpoints and decision-making in a regime practising extensive politics of race segregation. The intimate relations between Norwegian missionaries and settlers are also documented by the South African historian Frederick Hale.13

The NMS was the first missionary organisation established in Norway, and ‘the Zulu-mission’ was its pioneer enterprise, before a second mission was established in Madagascar in 1866 and a third in China in 1902. As in other Western countries, the extensive interest in foreign missions emerging in early nineteenth-century Norway was above all a product of voluntary commitment on the part of individuals and groups related to evangelical revivals and lay movements, who had transnational networks.14 Although some pastors in the official Evangelical-Lutheran Church were enthusiastic about the project, the modern idea of mission, that it was the task of Western Christians to bring the Christian faith to the masses of non-Christians abroad, was unfamiliar to the majority of the high-church clergy. Inspired by the readings of German and British missionary magazines, men and women started to form local missionary associations in the 1820s and 1830s. In August 1842, 82 male representatives from 65 of these associations, as well as 102 other men interested in missions, made their way to a mission council in Stavanger. The meeting ended with the establishment of a national society, the Norwegian Missionary Society, which was actually the first national organisation of voluntary local associations in the country, and introduced an era of immense growth in voluntary religious, political, economic and cultural societies and organisations, on both a local and a national level.15

Whereas the British missionary movement was founded on the pillars of denominational missionary organisations (Anglican, Baptist, Methodist, Congregationalist, Presbyterian, etc.),16 the Norwegian missionary movement was far more homogeneous. Although the NMS was a private and voluntary enterprise and not initiated by any church organisation, its Lutheran denominational foundation was accepted without question The NMS constitution of 1842 declared that its representatives in the mission fields should teach in accordance with ‘The Holy Script and the Church of Norway’s Confessional Scripts’.17 Schreuder, a university-educated theologian from an upper-class family, was himself ordained in accordance with the rituals of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Norway. His aim was to establish a Lutheran Church in Zululand in line with the Scandinavian folk-church model, which also explains why in an introductory phase of the mission work he put great effort into converting those in the upper strata of society, beginning with the king and the royal household.18 Schreuder acted, however, in accordance with the NMS as a Lutheran mission organisation and was in 1866 consecrated ‘missionary bishop’ of what was defined as ‘the Church of Norway’s Mission Field’. Although the majority of the NMS missionaries, unlike Schreuder, were recruited from the lower social classes, and the education they were offered at the NMS’s theological seminary never qualified them for employment in the State Church of Norway, they were ordained to serve as missionary pastors by state-church bishops. The relation between the NMS and the official Lutheran church continued to be close. Other mission organisations established in Norway in the last decades of the nineteenth century, both Lutheran and non-denominational, had a more distant relationship with the state church.19

In 1842 Norway was still under Swedish rule, but nevertheless had its own constitution, parliament and government. Although the nation can hardly be defined as a colonial power in the strict sense of the term – contemporary Norwegian nationalists claimed that the nation itself had a long history of being ‘colonised’ – Norwegians nevertheless participated in colonial encounters as sailors, soldiers, surveyors, ethnographers – and missionaries. The Norwegian historians Hilde Nielssen, Inger Marie Okkenhaug and Karina Hestad Skeie claim that missionaries not only participated in activities that had culturally and socially transforming effects on indigenous societies, but also that the missionary movement involved considerable activity at ‘home’ including representation of the people and cultures they encountered.20 Norwegian missionary activity must be studied in a colonial and post-colonial context, they claim, and they refer to recent scholarship which has pointed out that the ‘colonial culture’ had an impact on the European imagination of ‘self’ and ‘other’.21 In the course of the nineteenth century Norway had the highest number of missionaries per inhabitant in the world. The mission movement cut across boundaries of class, gender, occupation and education, and included people in the rural as well as the more u...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction: Missionaries and Masculinities

- Part I The Construction of Norwegian Lutheran Missionary Masculinity

- Part II Missionary Masculinity between Professionalism and Privacy

- Concluding Remarks

- Appendix: NMS Missionaries in South Africa, 18441930

- Notes

- Unprinted Sources

- Printed Sources

- Bibliography

- Index