eBook - ePub

Genre-based Automated Writing Evaluation for L2 Research Writing

From Design to Evaluation and Enhancement

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Genre-based Automated Writing Evaluation for L2 Research Writing

From Design to Evaluation and Enhancement

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Research writing and teaching is a great challenge for novice scholars, especially L2 writers. This book presents a compelling and much-needed automated writing evaluation (AWE) reinforcement to L2 research writing pedagogy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Genre-based Automated Writing Evaluation for L2 Research Writing by E. Cotos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Teaching Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Teaching LanguagesPart I

Designing Genre-Based AWE for

L2 Research Writing

Introduction

Part I of this book lays the groundwork for the development of genre-based AWE for L2 research writing. The first chapter discusses the research writing construct and pedagogical aspirations, establishing a much needed dialogue that involves prominent views in cognitive psychology concerned with writing development, in rhetoric concerned with writing as social practice, and in the English for Academic Purposes (EAP) area of applied linguistics concerned with developing the language skills needed for effective academic communication. The second chapter provides a bird’s eye view of the AWE state-of-the-art in order to then reinforce the theoretical and operational frameworks formulated in Chapter 3 and integrated in the conceptual design of the genre-based prototype introduced in Chapter 4.

1

Learning and Teaching Challenges

of Research Writing

Research writing poses a great challenge for graduate students who are novice writers struggling with transitioning from peripheral to full participation in the discourse of their disciplinary community. At the same time, teaching research writing is often daunting for writing instructors due to the unfamiliar disciplinary conventions of research genres. Addressing these learning and pedagogical challenges necessitates an understanding of the individual-cognitive and socio-disciplinary dimensions underpinning research writing. In this first chapter, I elaborate on what these dimensions entail and how they intertwine in the construct of research writing competence. To further reason about how that applies to L2 research writing pedagogy, I discuss two epistemologically different genre teaching traditions – linguistic and rhetorical. I then put forth a rationale for enhancing L2 research writing instruction with genre and corpus-based AWE technology that can foster fundamental linguistic and rhetorical principles.

1.1 Research writing essentia

1.1.1 The cognitive dimension of research writing

L2 writers often think of writing as a language skill, and of research writing as a more advanced language skill, which can be perfected through brainstorming ideas, drafting, revising, and editing. While there is some truth to this perception, it is not entirely accurate. Research writing is arguably much more than such a linear sequence of steps. It is a process of knowledge transformation rather than transmission1 (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987) and is thus definitely ‘not just a mopping-up activity at the end of a research project’ (Richardson, 1998, p. 345), or a write-up as it is often referred to. It is a process that involves intense cognitive activity to create comprehensive outcomes of various forms of academic inquiry. Badley (2009b) sees research writing as a constructive, creative, and transformative process of knowledge in the making. Assuming Dewey’s (1991) view of learning from experience, he characterizes it as a dynamic and highly reflective process on the part of the writer, during which knowledge is constructed, deconstructed and reconstructed; concepts are connected, disconnected, and reconnected; and ideas are shaped, mis-shaped, and reshaped (Badley, 2009a, p. 209).

The complex cognitive paths and mechanisms triggered in the process of research writing can be described through the prism of cognitive models of writing that have evolved over the last 30 years. Flower and Hayes (1981), who proposed the most well-known cognitive process theory of writing of our contemporaneity, posited that writing as a process unfolds in a continuous series of reflective, generative, and inventive actions that activate the facets of individual cognition. Their theory explains writing as a set of distinctive thought processes that can be hierarchically organized and embedded in one another by the writer, for whom writing is goal-oriented. Their writing model contains three recursive processes – planning, translating, and reviewing. Planning entails creating an abstract internal representation of what the written prose would be. This representation is formed by generating ideas, giving those a meaningful structure, and by setting procedural and substantive goals (for example, how to begin and what content to present for what purpose). Translating is ‘essentially the process of putting ideas into visible language’ (p. 373). Reviewing is sub-divided into evaluative appraisal and actual modifications of the text. These two evaluation and revising sub-processes were expanded by Bereiter and Scardamalia (1983) who put forth the so-called compare-diagnose-operate (CDO) model, according to which when writers revise they first compare what they wrote with the mental representation of what they wanted to write. This comparison should result in diagnosing potential problems and then operating, or changing the text.

The importance of revision-oriented diagnostic operations was further substantiated in modified cognitive models with added processes and knowledge sub-stages (Flower et al., 1986; Hayes et al., 1987). The processes sub-stage includes evaluation in the form of reading to comprehend and identify problems, strategy selection, and modification of the writer’s internal and/or external representation of the text. The knowledge sub-stage includes the goals, criteria, and constraints that define the writing task; detection of ill-defined and diagnosis of well-defined representations of the problem; and the revision procedures intended to improve the text. This modeling approach therefore encompasses a much more complex reviewing process, where the cognitive path for evaluation and revision clearly relies on reflective reading. Reading allows writers to evaluate whether the written text representation corresponds with the intended mental representation and, consequently, to detect or diagnose the cause of the mismatch and to identify a suitable correction strategy.

Revision is also contingent on well-developed metarhetorical, metastrategic, and metalinguistic awareness (Horning, 2002). These types of metacognitive awareness are ingrained in the internal processes activated when writers evaluate their text, detect a need for revision, and engage in strategy selection (Chenoweth & Hayes, 2001). Most novice writers lack this awareness, and their ability to detect and diagnose problems when revising, or, as Flower et al. (1986) put it, ‘to see a problem in the text as a meaningful, familiar pattern’ (p. 48), is weak. The same can be said about novice L2 research writers. Academic writing instruction needs to help them develop metacognitive awareness to improve this diagnostic ability, as it is often the most important cognitive factor in successfully revising texts, both on a surface and global level.

1.1.2 The socio-disciplinary dimension of research writing

Acknowledging the role of cognition, Viete and Ha (2007) compare creative knowledge construction in research writing to the making of a quilt because it requires investment of self, efforts, and time, but, most importantly, because its ‘impact depends upon the expectations of the reader and the echoes of other texts in the mind of this reader as much as it does on the craft of the writer’ (p. 39). This quote underscores the social dimension of research writing, which presupposes intricate interactions between the writer and the readers as the former engages with the latter to create texts (Hyland, 2002, 2004a). Li (2006) explains that in writing as social interaction, authors shape their texts in a way that meets the expectations of the target readership. This underlying conversation with the disciplinary audience makes texts a place where writers and readers intersect for meaning making (Hyland, 2002). More specifically, writers are not simply transmitting meaning, but rather co-creating it in view of someone else’s reading and interpretation (Badley, 2009b). They are intertwining their ideas with the readers’ anticipated critical stance so that challenging it is justified and accepted.

The socio-disciplinary interaction is well-enveloped by genres, which have evolved as a response to the social interactions within disciplines (Bazerman, 1988) and to the socio-disciplinary forces that institutionalize their conventions (Paltridge, 2002). Genres have traditionally been defined as text types with shared communicative purposes that are achieved by means of a set of discourse conventions including overall organization and lexico-grammatical choices (Swales, 1990). These text types are ‘conventionalized forms of writing […] by which knowledge and information get disseminated to a community of people with shared interests’ (Ramanathan & Kaplan, 2000, p. 172). According to Berkenkotter and Huckin (1995), genres are also ‘inherently dynamic rhetorical structures that strategically package content in ways that reflect the discipline’s norms, values, and ideology (pp. 1–3). Research-related genres such as research articles, conference papers, theses, and grant proposals reflect the preferred discourse practices of the scientific community since they ‘are grounded in disciplinary ways of knowing’ (Paxton, 2011, p. 54). To engage in this particular type of social practice, writers draw on and conform to the representational resources of genres (Lillis & Scott, 2007) as vehicles that help create meaningful and intelligible communication with the members of the disciplinary community. Displaying such conformity is an important way of achieving consensus and making an impact on the discipline (Hyland, 2000).

I opened the discussion with the individual-cognitive and socio-disciplinary dimensions of research writing to contend that it should not be treated as a passive compilation of empirical outputs accrued and shared by individual authors or co-authors. On the contrary, research writing is a process that is contemplative, intellectual, and introspective, and communicative, interdiscursive, and communal. To successfully and productively engage in this process, L2 research writers need to be able to create texts that put forward credible and temporal scientific claims in ways that are acceptable by a social structure with an established system of practices called a discourse community (Giddens, 1979). This requires an advanced competency, which has yet to be explicitly defined as a construct. To arrive at a pedagogically informative description, I will further consider some insights from the socio-cognitive genre theory (Berkenkotter & Huckin, 1995; Bhatia, 1993).

1.1.3 Research writing competence

The ability to read and write academic texts has received the ostensible definition of academic literacy (Spack, 1997). Research writing can be considered an essential competency of a highly specialized academic literacy (Belcher, 1994). This competency involves reading that is no longer for comprehension but rather for reflective, critical evaluation. Badley (2009a) calls it ‘de-constructing’ scholarly texts, that is ‘trying to tease out, for own critical appreciation and understanding, how a writer as maker or fabricator has gone about constructing and shaping that text’ (p. 213). He suggests that deconstructive reading, through analysis, evaluation, and interpretation of literature, prepares authors to re-evaluate and re-interpret texts in a re-constructive synthesis, which is the writing itself.

The contours of this re-constructive synthesis are shaped by research genres, conceptualized by socio-cognitive genre theorists as a dynamic rhetorical ‘form of situated cognition embedded in disciplinary activities’ (Berkenkotter & Huckin, 1995, pp. 3–4) and used by writers in recurrent communicative situations to inculcate experience and meaning. Research genre writing thus can be viewed as applied metacognition (Hacker et al., 2009). As a process, it unfolds in a sequence of goal-oriented mental actions that involve monitoring and metacognitive awareness (Dunlosky & Metcalfe, 2009; Schraw & Dennison, 1994). Metacognitive awareness comprises knowledge of concepts relevant to the genre-related rhetorical task and knowledge of how to apply the concepts to complete the rhetorical task (Flower & Hayes, 1981). Research writing also involves metacognitive decisions with respect to genre-relevant features of content, organization, and style (Negretti & Kuteeva, 2011). Furthermore, it intertwines the metapragmatic ability to effectively convey scientific content and develop claims by routinely connecting rhetorical purposes with the symbolic resources of the target research genre (Berkenkotter et al., 1991; Hyland, 2000). These ‘representational resources’ (Kress, 1996, p. 18) are textual and linguistic features the use of which is necessary to realize intended communicative purposes.

It follows that research writing embodies the persuasive nature of knowledge created as a web of interrelated discipline-specific interactions in a rhetorically and linguistically explicit argument (Bazerman, 1988). It is ‘essentially rhetorical behavior’ (Jolliffe & Brier, 1988, p. 38) that seamlessly blends in the understanding of the rhetorical problem, awareness of the ways of knowledge construction established by the discourse community, and ability to use discipline-specific conventions and appropriate functional language. Tardy (2009) covers these aspects in her definition of genre knowledge, which contains four overlapping domains: rhetorical knowledge, formal knowledge, process knowledge, and subject-matter knowledge. Rhetorical knowledge ‘captures an understanding of the genre’s intended purposes and an awareness of the dynamics of the persuasion within a socio-rhetorical context’, for example writer’s positioning and readers’ expectations and values. Formal knowledge refers to ‘textual instantiation of the genre’, that is the structure, discourse form, and lexico-grammatical conventions. Process knowledge comprises ‘all of the procedural practices associated with the genre’, such as the reading practices of the audience and the composing processes of the writer. And subject-matter knowledge includes knowledge of ‘the relevant content’ reflecting disciplinary expertise (p. 21). The description of formal knowledge can be extended to include the elements of discourse competence, which appears in different communicative competence models that integrate linguistic aspects with the pragmatics of creating conventionalized forms of communication (Bachman, 1990; Canale, 1983; Canale & Swain, 1980; Celce-Murcia et al., 1995). In general, genre knowledge is an abstract but systematic construct, and it is ‘conventional in that form and style may be repeated’ (Johns, 1997, p. 22).

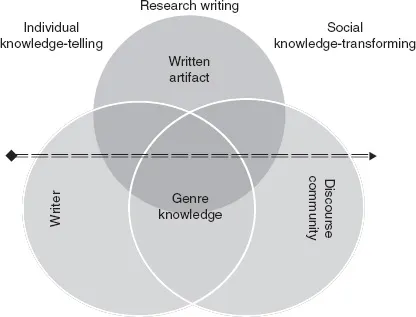

On the grounds of this deliberation, a pedagogically informative definition of research writing competence as a component of advanced academic literacy should forefront the role of both individual cognition and socio-disciplinary factors. Ergo, I would describe research writing competence as the fusion of the writer’s self-awareness and metacognitive knowledge of the rhetorical task, socio-disciplinary awareness about the discourse community, and metapragmatic ability to produce a research writing artifact as a communicative action realized with genre-specific language choices that are appropriate to the expectations of the disciplinary discourse community. Figure 1.1 illustrates the intersections among these elements, at the heart of which is genre knowledge. With the acquisition of genre knowledge, the overlap will increase, which means that the writer will advance from knowledge-telling to knowledge transforming, being able to create written artifacts, or texts representative of a given genre, that are congruent with the values of the target socio-disciplinary practice.

In view of this definition of research writing competence, L2 writing instruction should reinforce students’ cognitive processes as well as the social and cultural practices surrounding research-related genres. Centering on the acquisition of the genre knowledge, it should provide abundant connections between scholarly reading and writing processes and ‘[m]ediat[e] the engagements of knowers with the knowledge represented by academic discourses […] through the medium of language’ (Hyland & Hamp-Lyons, 2002, p. 6). In Hyland’s (2000) words, teachers must ‘involve [students] in acquiring a metacognitive awareness of [genre] forms and contexts and a familiarity with the discoursal strategies they need to perform roles, engage in interactions, and accomplish goals in the target community’ and help them ‘gain an awareness of the discipline’s symbolic resources for getting things done by routinely connecting purposes with features of texts’ (p. 145).

Figure 1.1 Research writing competence

L2 research writing pedagogy should also be informed by the results of numerous studies that have examined academic writing produced by second language learners for more than four decades (see Belcher & Braine, 1995; Hamp-Lyons, 1991). Much of this research strand has not only confirmed the need to help students develop genre knowledge and become competent research writers, but also provided a baseline for instruction by revealing the nature of novice scholars’ writing difficulties.

1.1.4 Research writing of L2 novice scholars

For L2 writers, who are under an increasing pressure to publish in English-dominant international journals (Flowerdew, 1999), writing about research in English is a very effortful and at times an agonistic challenge. It is not uncommon for them to ascribe their major difficulties to a lower level of language proficiency (Bitchener & Basturkmen, 2006; Mohan & Lo, 1985), and their manuscripts are indeed not without language issues. While the so-called non-standard English is generally tolerated by the gatekeepers (Flowerdew, 2001), it is often viewed as less than desirable (Li, 2006) or criticized for being almost unintelligible due to a high proportion of lexico-grammatical errors (Ammon, 2000; Coates et al., 2002). Previous studies identified a number of problems such as inaccurate use of grammatical forms and inappropriate vocabulary choices along with different writing mechanics issues (Casanave & Hubbard, 1992; Cooley & Lewkowicz, 1995, 1997; Dong, 1998; Surratt, 2006). In addition, learner corpora research reveals patterns of misuse, overuse, and underuse of linguistic features (Gilquin et al., 2007; Granger, 2009). Misuse of conventionalized language at the level ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part 1: Designing Genre-Based AWE for L2 Research Writing

- Chapter 1: Learning and Teaching Challenges of Research Writing

- Chapter 2: Automated Writing Evaluation

- Chapter 3: Conceptualizing Genre-Based AWE for L2 Research Writing

- Chapter 4: Prototyping Genre-Based AWE for L2 Research Writing: The Intelligent Academic Discourse Evaluator

- Part 2: Implementing and Evaluating Genre-Based AWE for L2 Research Writing

- Chapter 5: Exploring the IADE Genre-Based Prototype

- Chapter 6: Evaluating the IADE Genre-Based Prototype

- Chapter 7: From Prototyping to Principled Practical Realization

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index