eBook - ePub

Development Strategies, Identities, and Conflict in Asia

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Development Strategies, Identities, and Conflict in Asia

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Development Strategies, Identities, and Conflict in Asia explores the links between Asian governments' development strategies and the nature and dynamics of inter-group violence, analyzing variations in strategies and their impacts through broad comparative analyses, as well as case studies focused on eight countries.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Development Strategies, Identities, and Conflict in Asia by William Ascher, N. Mirovitskaya, William Ascher,N. Mirovitskaya in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

War, Peace, and Many Shades in Between: Asia in the New Millennium

William Ascher and Natalia Mirovitskaya

“Asia is rich in people, rich in culture and rich in resources. It is also rich in trouble.”1

The cradle of world’s oldest civilizations and major religions, Asia has seen and is still experiencing all variations and consequences of armed violence2—from the devastation of international and civil wars, to brutal repressions by militarized regimes; from long-lasting insurgencies and separatist struggles, to explosions of religious and communal violence and terrorism. Its extreme diversity and rich dynamics of economic and political development make Asia a perfect setting to explore the multiple pathways that connect economic development to intergroup relations. This chapter sets the stage for this inquiry. It begins with a brief summary of the current status, major trends, and evolving nature of intergroup violence in the region. We also identify major challenges for conflict-sensitive development and some new threats that may undermine human security in the region. We conclude the chapter by introducing the case studies selected for this volume and their major findings. The next chapter presents an assessment of the variety and evolution of development strategies as they were designed and implemented within different countries.

The Research Project

The main focus of the research project is on the multiple linkages between government choices—development strategies and policies and the institutional changes to promote such strategies—and the likelihood of intergroup violence or cooperation. Understanding constructive and destructive pathways is essential for designing conflict-sensitive development approaches. The pathways linking economic strategies and policies to the likelihood of violence are located within four broad dimensions: predispositions, opportunities, incitement, and deterrence. We assume that violence is more likely if people are primed (predisposed) for hostility against other group(s) or the state, which may favor such other group(s), or at least be perceived as allied with them. The concrete opportunity to engage in hostilities and remain in confrontation will determine the likelihood that predispositions will ignite overt outbreaks of violence (riots, pogroms, or rebellion,) or sustain its perpetuation (insurgency, civil war). Thus violence strongly depends upon political, economic, and social opportunities of potentially conflicting groups, as well as on the degree of their radicalization, organization, and acceptance of violence as legitimate or necessary behavior. Triggering events, including leaders’ actions, incite overt intergroup violence (and may contribute to escalation), unless specific deterrence mechanisms override these other factors.

Development initiatives may affect these mechanisms via various pathways—from the initial stage when development initiatives are considered, to the selection of particular combinations of policies and institutional changes, to implementation and subsequent impacts on groups’ economic roles, resources, and relative power, as interpreted by various actors. Asian development experiences provide ample opportunities to explore these connections.

Can Asian policymakers find development strategies that minimize violence while still overseeing healthy economic improvement? Some Asian nations have been surprisingly peaceful—in contrast with earlier predictions—while still progressing impressively in economic terms: Malaysia, following an anti-Chinese massacre in 1969; South Korea, as it successfully transitioned to democracy. The relative peace of economically advanced countries—Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore—gives more hope. However, other nations, earlier thought to be promising in terms of peaceful growth, have foundered badly in both respects; Sri Lanka is probably the most extreme case. While economic structures and development strategies are certainly not the exclusive drivers of peace and prosperity, they are often prominent factors alongside of domestic political and social causes and international interactions. The cases presented in this volume demonstrate that economic policy initiatives often antagonize groups against the government, and against other groups seen as allied with the government. In other cases, the policies, or their consequences, have threatened particular groups to the point that their members became desperate enough, or simply angry enough, to initiate aggressive actions. Some policies put groups into confrontation, such as competition over property rights. In other cases, modernization policies that reconfigured group economic roles have reinforced negative stereotypes (i.e., perceptions of exploitative Chinese agricultural merchants in Indonesia or Sinhalese businessmen in Sri Lanka). Other initiatives bring people from different ethnic and religious groups into close proximity, magnifying the likelihood of clashes. Yet other policies propel individuals into the role of violence provocateurs, by denying them better opportunities or exposing them to radicalized education.

A broad review of Asia’s conflicts reveals illuminating surprises. First, East Asia3 has thus far reversed the patterns of large-scale violence that plagued the region prior to the 1980s. Tønnesson (2009, 111), referring to both international and intrastate conflict, observes that “since 1979, East Asia has been surprisingly peaceful.” The Human Security Report (2011, 45) judges that in terms of violence, “over the past three decades, East Asia has undergone an extraordinary transformation. From 1946 to the end of the 1970s, it was the most war-wracked region in the world.”

Second, despite fears of imminent carnage, the several million Russians remaining in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan)4, have suffered remarkably little violence by the majority populations. However, violence toward other Asian and North Caucasian minority groups in all five republics has sometimes been acute, while Central Asian and North Caucasian migrants remain targets of extreme xenophobia and racial violence in Russia. Meantime, in Russia’s North Caucasus regions, anti-Russian violence against both government forces and civilians has been persistently high, as Mikhail Alexseev’s contribution to this volume demonstrates.

Third, in East and South Asia the most explosive current conflicts do not reflect the resentment against governments for neglecting the least developed areas within countries, but rather they reflect the clashes that emerge from efforts to develop those areas.5 This important motif demonstrates the convergence of resettlement, natural resource, and regional development strategies.

Fourth, although it is plausible that poverty would engender resentment and increase the desperation in struggles for wealth, in some of the poorest Asian countries violence has been more likely in wealthier areas.6 It is unclear whether this reflects urbanization that shifts poverty and resentment to cities, whether wealthier areas bring potentially antagonistic groups into proximity, or the capacity to mobilize violence is greater in wealthier areas.

Fifth, the liberalization reforms that brought acute disruption all over Latin America and in many African countries have generally been enacted with far less turmoil in Asia. Much of Asia’s general success in economic growth is owed to the elimination of inefficient state interventions.

Sixth, despite the widespread preference of elites for education and health care that benefit their own strata (through budgetary emphasis on higher education and curative medicine), several East Asian nations have had extraordinary success in educating children from low-income families and improving the population’s overall health status. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia owe much of their economic productivity and societal stability to social-service investments targeting the poor, and to increasing economic mobility.

These counterintuitive patterns demonstrate the need to get past the conventional wisdom and unexamined assumptions about the links between economic development strategies and intergroup conflict.

The Scope and Location of Violence in Asia

Assessing violence trends is fraught with underreporting, inconsistent definitions, and deliberate manipulation by official or unofficial information sources. Various databases present conflicting evidence.7 Some sources indicate that although violence patterns have changed substantially through the past decades, the region in general is still one of the world’s most conflict-prone. In 2011, out of 388 conflicts observed globally and judged as warranting inclusion in the Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research dataset (2012), nearly a third occurred in Asia and Oceania.8 In addition to wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, and violence in the context of the Arab Spring, the intensity of internal violence increased in 2011 in Turkey, Iran, Thailand, Cambodia, and Myanmar.

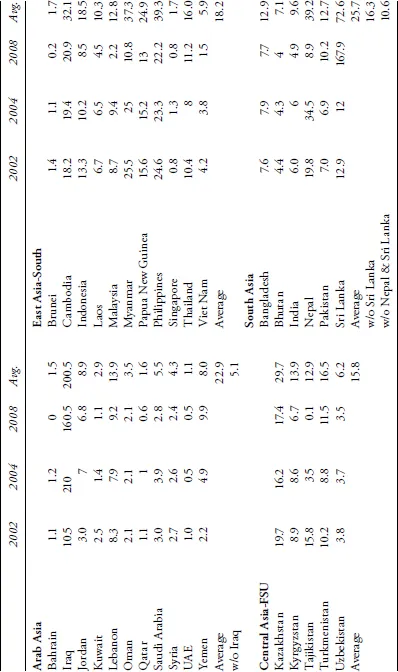

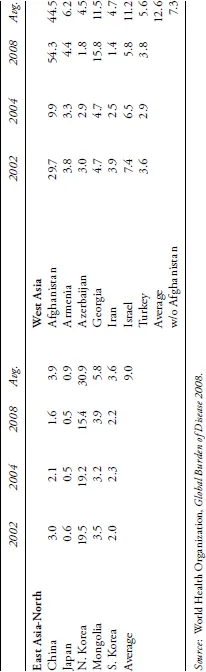

One approach to assess broad violence patterns is to use World Health Organization (WHO) data on deaths from intentional injuries and war, compiled from government figures.9 For the first decade of the new millennium, WHO has figures for 2002, 2004, and 2008, displayed in Table 1.1.

Apart from the countries engaged in international wars (Afghanistan and Iraq) and straightforward civil wars (Nepal and Sri Lanka), most countries have quite similar figures for the three years, lending confidence in the results, although this does not address underreporting across different countries. For example, the 2008 recorded rate for Indonesia is 10.2 deaths per 100,000 people from intentional injury and war (World Health Organization 2009). Yet Varshney (2010, 6), reviewing more intensive analyses of riots, pogroms, and lynchings, argues that “the scale of ethnocommunal violence in Indonesia does appear to be enormous.” The underreporting often occurs in rural areas where state presence is low. A World Bank (2010, 1) assessment of Indonesian violence in just six provinces concluded that

high levels of routine violent conflict . . . have resulted in 2,000 violent conflict incidents on average per year since 2006, in areas accounting for only 4 percent of Indonesia’s population. During 2006–2008, these conflicts led to over 600 deaths, 6,000 injuries, and the destruction of more than 1,900 buildings.

Table 1.1 Violence Rates in Asia, 2002, 2004, 2008

Individual country rates can be supplemented by comparisons provided by the Geneva Declaration Secretariat. These subregional rates demonstrate that despite the reputation of all Asian subregions for notoriously violent cases—Iraq in Arab Asia, Chechnya within the Russian Federation, Cambodia and Vietnam in East Asia, Sri Lanka in South Asia, and Afghanistan in Western Asia—the levels of recorded fatalities in the first decade of the 2000s were relatively low compared to the developing regions of Africa and Latin America. For the 2004–2009 period, Central America’s fatalities (29 deaths from violence per 100,000 population), Southern Africa (27), the Caribbean (22.5), Middle Africa (19), and South America (18) were far higher than in South Asia (10), West Asia (7.5), Central Asia (6.5), Northeast Asia (5.5), and Southeast Asia (4). Only West Africa (9) was lower than the highest Asian subregion.10

However, peace in many parts of Asia is fragile. Conflicts may remain dormant for years and suddenly flare-up (e.g., the 2012 Armenian-Azerbaijan clash over Nagorno-Karabakh); they may be chronic and deteriorating over a long period, or erupt in unexpected ways. Many Asian conflicts have been protracted and although as of 2012 most are of low intensity and are localized in specific geographical areas (e.g., Mindanao in the Philippines), some are spreading (e.g., Pakistan). After a respite from violence in the first decade of this century, major violence flared in the Ferghana Valley, as more than 400 people were killed in Kyrgyz-Uzbek riots in southern Kyrgyzstan, and roughly 100,000 Uzbek residents fled to Uzbekistan. According to the International Crisis Group (2012b), the ultranationalist Kyrgyz government leaders in southern Kyrgyzstan have been provoking anti-Uzbek sentiment for both political and economic objectives:

Uzbeks are subject to illegal detentions and abuse by security forces and have been forced out of public life . . . Uzbeks are increasingly withdrawing into themselves. They say they are marginalised by the Kyrgyz majority, forced out of public life and the professions; most Uzbek-language media have been closed; and prominent nationalists often refer to them as a diaspora, emphasising their separate and subordinate status . . . While Uzbeks are far from embracing violence and have no acknowledged leaders, their conversations are turning to retribution, or failing that a final lashing out at their perceived oppressors.

According to Kyrgyzstan’s acting president, the violence was far worse, with nearly 2,000 people killed (Harding 2010). If true, the death rate from that episode alone would account for a rate of 36 fatalities per 100,000.

The new decade has also seen violence associa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Chapter 1 War, Peace, and Many Shades in Between: Asia in the New Millennium

- Chapter 2 The Nexus of Economic Strategies and Intergroup Conflict in Asia

- Chapter 3 Tribal Participation in India’s Maoist Insurgency: Examining the Role of Economic Development Policies

- Chapter 4 Intrastate Conflicts and Development Strategies: The Baloch Insurgency in Pakistan

- Chapter 5 Development Strategies, Religious Relations, and Communal Violence in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia: A Cautionary Tale

- Chapter 6 Exploring the Relationship between Development and Conflict: The Malaysian Experience

- Chapter 7 Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Conflict: A Case Study on Japanese ODA to Vietnam

- Chapter 8 Socioeconomic Change, Intraethnic Competition, and Political Salience of Ethnic Identities: The Cases of Turkey and Uzbekistan

- Chapter 9 Local versus Transcendent Insurgencies: Why Economic Aid Helps Lower Violence in Dagestan, but not in Kabardino-Balkaria

- Chapter 10 The Conflict-Development Nexus in Asia: Policy Approaches

- Index