eBook - ePub

Football Hooliganism, Fan Behaviour and Crime

Contemporary Issues

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Football Hooliganism, Fan Behaviour and Crime

Contemporary Issues

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Focusing on a number of contemporary research themes and placing them within the context of palpable changes that have occurred within football in recent years, this timely collection brings together essays about football, crime and fan behaviour from leading experts in the fields of criminology, law, sociology, psychology and cultural studies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Football Hooliganism, Fan Behaviour and Crime by M. Hopkins, J. Treadwell, M. Hopkins,J. Treadwell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Football as a Crime Generator

1

The Football ‘Hotspot’ Matrix

Introduction

Reflecting the concerns of much orthodox criminology, research on football-related crime and disorder has so far focused mainly on identifying underlying causes of the dispositions shown by some supporters to behave in criminal and antisocial ways: for example, what biological (Buford, 1991), developmental (Marsh, 1978), social (Armstrong, 1998; Dunning et al., 1988; Robson, 2000) or political (Taylor, 1971; Clarke, 1978) conditions lead individuals and groups to become ‘hooligans’?

This chapter takes a different tack. It is rooted in heterodox, environmental criminology whose concern is not so much with offenders and their dispositions to offend as with patterns of crime events: where and when are incidents of crime and disorder found, and how are patterns in them produced? Environmental criminology is also determinedly applied. Thus, its findings are importantly orientated to what can be done in practice, in the relatively short term, to deal with crime-related problems. The term ‘administrative criminology’ is sometimes used to disparage the form of criminology used in this paper (Wortley, 2010). If by this is meant criminology that speaks pragmatically to policy options to reduce crime harms in the relatively short term, we wholeheartedly embrace it. If it assumes that the conclusions are uncritical of the status quo, as will become clear as this chapter unfolds, we would repudiate it. Finally, although far from atheoretical, environmental criminology sets great store by making systematic use of available evidence: even when the available evidence is imperfect, it is deemed preferable to mere speculation.

The question about football-related crime and disorder patterns focused on in this chapter is ‘How far and over what period do football-related crime and disorder incidents extend around football grounds?’ The policy questions to which the research was directed are ‘Over what time and space is special provision needed to police football matches adequately?’ and, related to this, ‘Over what time and space might it be reasonable to ask football clubs to make a contribution to the costs of policing football matches?’ To inform discussion of these questions, an empirical analysis is presented for Elland Road football ground in Leeds. The data used for this purpose are police-recorded crime incidents that occurred in and around the stadium for the period 2004–2010.

Background

At the time of writing, Leeds United Football Club and West Yorkshire Police (WYP) are locked in an ongoing legal battle (BBC, 2012) over who should be financially responsible for policing crimes that occur on private property away from Elland Road. In the first instance Leeds United prevailed, with a judge indicating that WYP could not charge for publicly owned land that extends beyond the geographical proximity of Leeds United’s private property. An appeal has been filed by the WYP against this landmark ruling and is scheduled to return to the High Court in 2013 (Yorkshire Post, 2013). This legal battle that Leeds United and WYP are embroiled in is not the first, but is the most recent, in an ongoing struggle between police forces in England and football clubs over payment for the policing of football matches that dates back to the 1920s (see Shortt, 1924).

Back in the 2003–2004 season, there was an earlier legal face-off between the police and football clubs over costs: Greater Manchester Police (GMP) proposed to increase the charges for police services to Wigan Athletic Football Club (Wigan AFC) after its promotion to Division One (presently the Championship) from Division Two (presently League One). Match attendance figures for Division One suggested that Wigan’s success would require increased numbers of police on match days, thereby justifying increased charges. Wigan AFC disagreed and withheld compensation for policing services for the duration of the 2003–2004 season, despite the ongoing provision of services by GMP. This situation persisted during the following season. Wigan AFC eventually made part-payment, but not enough to cover the costs incurred by GMP. GMP went to court to sue for the outstanding amount (£293,085). The courts initially ruled in favour of GMP, although this judgement was reversed on appeal.

In the first instance, the GMP v. Wigan AFC rulings appeared to produce clear guidelines on when and where it is appropriate to charge for football match policing, how much can be charged and the means by which decisions on the level of policing services should be made (see Kurland, Johnson and Tilley, 2011a, b, c, d, e, for a fuller explanation). However, GMP v. Wigan AFC, as with Leeds United v. WYP thus far, presented no empirical evidence on when and where it might be reasonable for the police to charge for their services. This failure by the police may have hindered their defence against football clubs, which, like all businesses, try to minimise their costs in order to maximise profits, and may ultimately have lost them the legal battle in the court of appeal.

Environmental criminologists assume that the risk of crime is not uniformly distributed across time and space and provide theory to help explain how the immediate environment can affect behaviour and why some environments are likely to be more criminogenic than others. Analytic techniques developed to examine such patterns are particularly promising for the production of an evidence base that speaks to reasonable levels of compensation by football clubs for policing crimes associated with games at their grounds. Furthermore, such findings may help the police and other crime prevention practitioners concentrate their attention on specific crime problems that tend to surface at certain times in certain locations (Wortley and Mazerolle, 2008).

Theoretical foundation

Routine activity theory is particularly suitable for understanding and addressing questions related to the location and time at which football-related crime occurs (Felson and Cohen, 1980; Madensen and Eck, 2011; Kurland, Johnson and Tilley, 2013). ‘Routine activity theory’ suggests that necessary conditions have to converge in time and space for a crime to be committed. That is, there has to be a ‘likely offender’ (such as an adolescent male) without an ‘intimate hander’ (someone such as a mother, sister, girlfriend or teacher who is capable of exerting leverage on likely offenders), alongside a ‘suitable target’ (such as a small, portable, high-value item) that lacks a ‘capable guardian’ (someone who is deemed able to protect the suitable target). There must also be no effective ‘place manager’ (someone who can oversee locations that would otherwise be crime hotspots; Felson and Cohen, 1980; Cornish and Clarke, 1986; Eck, 1994). According to routine activity theory, the supply, distribution and movements of these key actors determine the level and distribution of crime events.

Let us apply the routine activities approach to football matches. Football matches result in increased numbers of people (all of whom could be likely offenders, intimate handlers, suitable targets and/or capable guardians) in a concentrated location under conditions that are conducive to certain types of crime. Moreover, the crowds at matches provide anonymity for would-be offenders and distract potential crime victims. Thus, it seems reasonable to expect that the large numbers of spectators attending football matches would create fresh opportunities for crime, thereby potentially increasing the occurrence of offences at matches. Of course, supporters have to travel to games, and many fans will converge at locations such as pubs and at key transportation nodes near by leading to and from the football stadiums, providing further opportunities for crime in the surrounding areas. This convergence is episodic: people tend to arrive before kick-off and to leave after (or shortly before, depending on the score) the final whistle. As such, if football matches do influence levels of crime, then we would expect them to increase during the hours leading up to matches, during the match and after its conclusion, but not at other times of the day. In particular, an increase in violent crime might be expected at games as a result of the increased density of people and the provocations (see Wortley, 2001) caused by rival supporters’ interactions with each other (Rotton et al., 1978; Branscombe and Wann, 1992; Russell, 2004). At the same time, but with alternative precipitators, we would expect various forms of acquisitive crime, such as theft and handling and criminal damage, to increase because of a lack of supervision (Mustaine and Tewksbury, 1998) and the increased scope for stealth that would be available to offenders mingling with the crowd. More generally, recent research (Wilcox and Eck, 2011) suggests that busy places offer criminal opportunity, and so one expectation in the current study is that crime in and around Elland Road will increase on match days.

As with all football stadiums, the activity that takes place within Elland Road is episodic, occurring on only a fraction of days and at specific times. The intermittent use of Elland Road creates conditions whereby days that the stadium is not used can act as a counterfactual against which to compare patterns on days when it is (Kurland, Johnson and Tilley, 2010; 2014). By comparing match and non-match days, differences between both the spatial and temporal counts of match-related crime can be estimated.

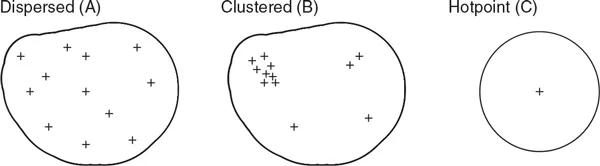

To describe variations in crime patterns more generally, Ratcliffe (2004) has devised a heuristically useful but simple taxonomy of crime hot spots. We draw on this to distinguish different profiles of spatio-temporal crime concentration associated with the timing of football matches at Elland Road. Ratcliffe suggests three broad categories of temporal hot spot – diffused, focused and acute – as well as three broad categories of spatial hot spot – dispersed, clustered and hotpoint. These provide for a three-by-three hotspot matrix. Figure 1.1 shows the three types of spatial hot spot. Dispersed hot spots (A) occur when a sufficiently large number of crime events take place across a particular area. This might occur within Leeds on match days, if there are a large enough number of crime events occurring at many different locations across the area around Elland Road. For instance, a significant number of crimes may occur at various pubs and fast-food establishments in the city centre in the hours leading up to the match in addition to some that occur at transportation links as well as inside the ground. For clustered hot spots (B), crime events occur throughout an area, but there is evidence of crime mostly clustering at one particular location. Theoretically, this is the type of spatial hot spot we would expect to see most on a football match day. In particular, we would anticipate observing many offences occurring immediately inside the stadium and the area directly outside it, with some additional match-day crime occurring at greater distances. Lastly, the hotpoint hot spot (C) is a setting where many crimes occur at the same specific location. If all match-day crimes took place within the football ground and none outside the ground, this would represent a hotpoint hot spot.

Figure 1.1 The three spatial hotspot categories of Ratcliffe’s (2004) hotspot matrix

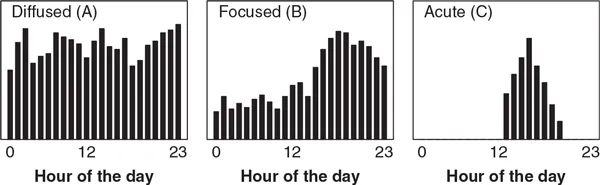

Similarly, the distinctions between the three types of temporal hot spot can be seen in Figure 1.2. For the diffused hot spot (A), it can be seen that the number of offences may rise and fall throughout the day (and night) but that there is a persistent risk of crime, whatever the time. This might occur at large-scale international football tournaments such as the World Cup, European Championship or Copa America that are staged in the same locations over a number of weeks thereby increasing the ambient population around a particular stadium over a longer duration. For the focused hot spot (B), while there is a general level of risk throughout the day, there is a heightened risk during a particular interval of time (night-time in the example shown). Theoretical expectations suggest that focused hot spots may occur at Leeds United. More explicitly, there is a distinct possibility that Elland Road is situated in an area that does experience some crime on days the stadium is not used, but the ecological changes associated with large numbers of people attending football matches have a profound effect on the level of crime during the hours before, during and/or after football matches take place. Finally, acute hot spots (C) are those where there is little, if any, associated risk for the majority of the day but there is a heightened risk for a relatively short period of time. There is also a distinct possibility that the patterns observed at Elland Road on match days will be resemble this profile.

Figure 1.2 The three temporal hotspot categories of Ratcliffe’s (2004) hotspot matrix

Categorising spatial and temporal hot spots using the hotspot matrix can aid understanding of how particular crime problems on match days are manifested and act as a guide to assist operational commanders and crime prevention practitioners in targeting appropriate prevention and/or detection strategies. While classifying and focusing on different types of hot spot could not replace the need for many of the generic tactics employed for maintaining the safety and security of supporters who attend matches, it would enable practitioners to home in on specific problem hot spots and evaluate crime prevention strategies that are specific to them (Ratcliffe, 2004). For example, if there were a clustered, acute hot spot for theft from vehicles on match days around Elland Road, one of several measures could be adopted in the area at the particular time when these offences occur. One preventative strategy might be to have uniformed officers or private security personnel in the area on bikes during these particular times. Alternatively, plain-clothes officers might work the same area if there was a desire to apprehend those engaging in this particular type of crime on match days.

Data and methods

WYP and British Transport Police (BTP) provided crime-type, time-stamped and geo-coded details for all recorded crime incidents that occurred within a three-kilometre radius of the centre of the Elland Road football ground for the six-year period from 2004 to 2010. These data were used to examine spatial and temporal patterns of crime around the stadium on days when the stadium was used and those when it was not. The fact that games were not played every week provided conditions for a ‘natural experiment’ where the use of the stadium (for football games) was ‘switched on and off’ in a quasi-random fashion, thereby providing near-equivalent populations of game and non-game days.

For the purpose of this chapter, we focus exclusively on criminal damage, theft-and-handling and violence-against-the-person offences, on the grounds that these three crime types have different motivations and precipitators (described above). Prior to aggregating the data, either spatially or temporally, the appropriate match and comparator days needed to be identified.

To do this, a list of all 138-match days that took place at Elland Road between the 2004–2005 and 2009–2010 seasons was assembled. Research has found considerable variation in the patterns of crime by day of the week (Brunsdon and Corcoran, 2006) and time of the year (Hird and Ruparel, 2007), and so comparison days were selected so as to be as similar as possible in all respects to the match days. For example, if a football match took place on a Saturday in November, then the closest previous or following Saturday without a football match was identified as the paired comparison day. A total of 125 comparison days that occurred either 7 days before or 7 days after a given match were identified. No comparisons could be identified within 7 days for 13 match days, and so 10 more relevant comparators were identified 14 days before or after these particular match days. Finally, 3 comparators were found for the outstanding 3 match days by expanding the search parameters to 21 days. This paired-date approach made it possible to determine whether the patterns of crime and incidents in and around Elland Road varied between match and non-match days.

The data for criminal damage, theft-and-handling and violent offences were extracted from the complete set of crime data provided by WYP and BTP, specifically for those days identified as either a match or comparison day. There were a total of 2,602 criminal damage events, of which 1,340 occurred on match days and 1,262 on comparison days. A total of 6,497 theft-and-handling offences took place, with 3,403 of those offences occurring on match days and 3,094 on comparison days. Finally, there were a total of 2,828 violent offences, of which 1,546 occurred on matc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- Part I: Football as a Crime Generator

- Part II: Exploring Fan Behaviour in the Global Media Age

- Part III: Criminalisation, Control and Crowd Management

- Index