eBook - ePub

The Labour Markets of Emerging Economies

Has growth translated into more and better jobs?

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Labour Markets of Emerging Economies

Has growth translated into more and better jobs?

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The past few decades have witnessed the economic and geopolitical rise of a number of large middle-income countries around the world. This volume focuses on the labour market situations, trends and regulations in these emerging economies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Labour Markets of Emerging Economies by Sandrine Cazes,Sher Verick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Labour Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

The process of development over the last two to three centuries has been built on the movement of people out of subsistence agriculture into more productive jobs in labour-intensive manufacturing. As captured by the writings of Arthur Lewis, Simon Kuznets and other development economists, this transition resulted in an increase in wages and household incomes, and subsequently, helped lift people out of poverty. This was the case in Western Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, and was fundamental for the success stories of the latter half of the 20th century such as the Republic of Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia and Thailand. Therefore, central to the process of development is the functioning of the labour market, namely, the ability for an economy to create more productive and better jobs for a large share of the population.

With the economic and geo-political rise over the last couple of decades of large middle-income countries such as China, India, Brazil, Indonesia and Turkey, considerable attention has moved to this set of economies, which have to varying degrees embarked on a rapid path to economic development. For this reason, this group of nations are often referred to as ‘emerging markets’ or ‘emerging economies’.1 Whatever title is given to this grouping, the contribution of these countries to the transformation of the global economy over the last few decades is without dispute: in 1990, emerging economies and developing countries represented just 30.8 per cent of world gross domestic product (adjusted for purchasing power parity). By 2012, this share had reached 50 per cent, and will continue to grow over the coming years. 2

During the past few decades, especially during the global boom years of the 2000s, these emerging economies expanded swiftly, with real GDP growing at well above the OECD average, and are indeed developing at far greater rates than witnessed in advanced economies during the industrial revolution. This acceleration in growth was driven by sound macroeconomic policies, significant productivity gains and an increasing integration into the world economy, providing greater access to new technology, capital and financial markets. This trend has been most notable in Asia, particularly in China, and more recently in India. Other large emerging economies such as Brazil, Indonesia and Turkey have also made substantial economic progress in recent years, which represents a major departure from previous decades that were characterized by macroeconomic volatility, economic crises and unsustainable economic models. In this regard, although the global financial crisis that began in the United States in 2007 did impact emerging economies, especially through the collapse in world trade in 2009, these countries either proved to be relatively immune to the shock or recovered quickly in 2010 and 2011. South Africa is one of the few large middle-income countries where the effects of the crisis have been longer-lasting, though this reflects persistent structural challenges in the economy and labour market rather than the nature of this recent shock itself.

However, trends in GDP growth do not provide the full story in terms of how emerging economies have progressed in translating material progress into broader development outcomes. Once the situation in these countries has been delved into, it becomes clear that success in a multi-dimensional context has been less consistent and positive. In terms of poverty reduction, all countries have made some inroads into tackling deprivation, albeit it at different rates and not without hitting stumbling blocks and reversals. This was most notable in China where the poverty headcount ratio (at $2 a day, adjusted for purchasing-power parity) fell at an unprecedented rate from 84.6 per cent in 1990 to just 29.8 per cent in 2008. Experiencing a few setbacks (the East Asian Financial Crisis and the 2005 cut to fuel subsidies), poverty has fallen at a slower pace in Indonesia with the headcount ratio dropping from 84.6 per cent in 1990 to 46.1 per cent in 2010. In Brazil, the poverty rate decreased from 30.0 per cent in 1990 to 10.8 per cent in 2009, while poverty reduction has been slower in India and South Africa.

Though poverty has fallen, growth has mostly been accompanied by increasing inequality in a large number of emerging economies, especially in Asia (notably in China), reflecting that the benefits of newly gained prosperity have not been evenly shared in the population. While this is in line with predictions of Simon Kuznets (that is, the inverse U-shaped Kuznets curve capturing the non-linear relationship between inequality and per capita income), it represents major challenges in terms of the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ in these countries. Indeed, in all emerging economies, there are segments of the population, such as specific racial and ethnic groups, that continue to miss out on the gains. Moreover, skills and spatial mismatches mean that individuals, especially youth, may have the wrong skills or live in the wrong places to be able to benefit from economic growth.

Ultimately, the key to understanding the relationship between economic growth and poverty/inequality in emerging economies is the centrality of the labour market in driving outcomes. In this regard, the labour market is the critical mechanism for lifting individuals and their families out of poverty. However, given that formal-sector job creation has been weak, informality, working poverty and vulnerable employment, all different indicators of decent-work deficits, continue to be the norm for most people in emerging economies. Moreover, women, youth and other segments of the population face barriers to accessing the few good jobs in the formal economy. Overall, promoting better outcomes in the labour market represents one the greatest challenges to emerging economies.

For this reason, the main themes of this book centre on the labour market situation, trends and regulations in emerging economies. While there is a wide range of publications providing a macroeconomic perspective or a focus on poverty and inequality (for example, OECD 2010), far less has been written on the labour markets of these countries. Moreover, in order to learn from the global financial crisis, it is crucial to reflect and compare different experiences and policy responses at the country level. This book attempts to fill this gap by addressing both short-term issues, particularly in relation to the global financial crisis, and longer-term challenges that stem not only from economic conditions, but also historical legacies and social factors.

Although this volume focuses on emerging economies (or large middle-income countries), the goal is not to provide sweeping generalizations about this group of countries. After all, the diversity in their labour markets is far more important than their commonalities. In this regard, the common trends witnessed in the worldwide boom years of 2002–2007 were more of a global phenomenon than one that was specific to these nations. At the same time, the increasing geo-political role of emerging economies means that a greater understanding of their labour markets is important, not only as an abstract academic exercise, but also as a means to raise a more general awareness of the situation in these countries. In addition to exploring the great diversity in the labour markets of emerging economies, this book focuses in more detail on four countries: Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey, which provide useful case studies given their country-specific challenges.

Brazil was once an economy prone to overheating and crises, which was driven by lax macroeconomic policy. In recent years, however, the government, starting with former President Luiz Inacio ‘Lula’ da Silva, adopted both a prudent macroeconomic policy approach and a social policy that has successfully brought down poverty and inequality. Indeed, Brazil is one of the few countries to have created a significant number of jobs in the formal sector in recent years.

Indonesia used to belong to the group of the East Asian ‘tigers’, along with Thailand and Malaysia. However, the East Asian Financial Crisis of 1997–1999 hit Indonesia much harder and resulted in a massive economic contraction, a commensurate rise in poverty and, ultimately, the fall of the Soeharto regime. Over the last seven years or so, Indonesia has managed to ‘re-invent’ itself through progress towards democratization and decentralization. Since 2005, the Indonesian economy has performed strongly thanks to its large domestic market and exports of commodities.

In contrast to the other three countries, South Africa has been burdened by the legacies of Apartheid, which resulted in some of the highest unemployment rates in the world. Despite being a commodity exporter, Africa’s largest economy has been unable to take advantage of the global commodity boom, and remains in a weak economic state that continues to be reflected by high unemployment rates.

Turkey is another country that has emerged from decades of crises and economic mismanagement to present itself as a modern, secular economy, which has grown strongly in recent years and been accompanied by robust job creation.

Therefore, while these four countries are different in terms of size and weight in the world economy, they have all experienced both periods of sustained growth and episodes of crisis. Though these countries are not the largest emerging economies, they are diverse in terms of their longer-term structural labour market challenges, which also reflect their very different historical contexts. These challenges have been tackled by governments through a range of interventions despite limited public services provision, low coverage of social insurance schemes and the high incidence of informality. More recently, policymakers in the four countries have all sought to mitigate the impact of the global financial crisis through stimulus packages, but with emphasis on different policies and areas of intervention.

By focusing on Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey, this volume, therefore, contributes to broadening the debate and discussion on the rise of emerging economies, which is usually limited to China and India (or the BRICs, that is, Brazil, the Russian Federation, India and China). All four countries chosen are already strategic players in their respective regions as reflected by not only their economic importance, but also their role as political players at the regional and global level. With respect to the latter, these countries are all members of the G20 grouping, and have actively sought to improve global governance in such areas as financial regulation and policy coordination. Moreover, to ensure broader relevance, findings are presented, mostly in chapters 2 and 3, on the most prominent and largest emerging economies, China and India,3 and other middle-income countries such as Argentina, Mexico and the Russian Federation.

Relevant to a wider discourse on labour market policies and institutions, the book addresses much debated themes such as the role of employment protection legislation and minimum wages in these countries. However, the volume goes beyond the normally narrow debate on their detrimental effect on labour market outcomes by providing a comprehensive coverage of how labour market policies, such as training and public employment programmes, have been utilized in these countries over recent years, especially during the global financial crisis.

In summary, there are three key and interrelated themes woven throughout this book:

A mixed picture on labour market outcomes: Despite strong economic growth, the labour market in most emerging economies continues to be characterized by informality and the lack of better jobs in the formal economy. Moreover, many jobs that are created tend to be precarious, which is indeed linked to their increased integration in the global economy. In terms of micro-level factors, one of the main drivers of labour market outcomes is education. Indeed, the challenge is not only the lack of education and training, but the phenomenon of a mismatch between the supply of skills and those demanded by employers. Against this longer-term context, the global financial crisis did not fundamentally change the overall trends in the labour market of these large middle-income countries.

Increasing use of labour market policies to address structural challenges and crises: In contrast to earlier decades, emerging economies are increasingly developing and implementing labour market policies to address both structural and demand-related unemployment and underemployment such as public employment programmes, entrepreneurship incentives, and training, often targeting women and youth.

Labour market institutions can play a positive role but their effectiveness remains a challenge: While there has been a strong tendency around the world towards deregulating labour markets, emerging economies are showing that regulations such as minimum wages can be used effectively to address poverty and inequality, without hampering formal-sector job creation. Institutions also have an important role to play during crises because they provide protection to workers. At the same time, many regulations in these countries are not adequately enforced, which needs to be addressed with respect to improving job quality and efficiency.

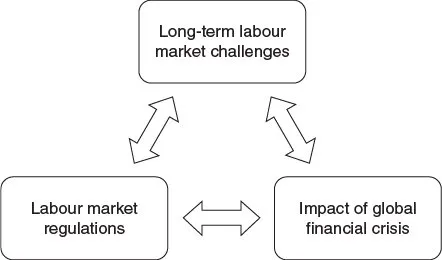

As illustrated in Figure 1.1, these three themes are interrelated. Firstly, the longer-term structural problems/trends in emerging countries have been a key determinant of the impact of the global financial crisis. For example, in South Africa, the high level of unemployment and weak attachment to the labour market among the African population left this group vulnerable to the global financial crisis, which hit the country in 2009. At the same time, the danger of any crisis is that the fall in aggregate demand results in more permanent damage to the labour market such that a short-term economic downturn leads to a worsening of (structural) unemployment, underemployment and other outcomes. This well-known lag in the labour market following a crisis has been described in IMF (2010) and Reinhart and Rogoff (2008). That said, the resilience of many emerging economies to the impact of the global financial crisis is testimony to an increasing robustness of the labour market, at least in quantitative terms.

Figure 1.1 The structure of the book – linkages between long-term structural challenges in the labour market, the impact of the global financial crisis, and labour market regulations (policies and institutions)

Structural unemployment is typically associated with the problem of a skills mismatch or the impact of labour market regulations. In terms of the latter issue, there has been a long-running and highly controversial debate on the effect of such institutions as employment protection legislation and minimum wages on unemployment; indeed, it was seen by many economists as a major reason why unemployment was higher in Europe than in the United States. In emerging economies, the relationship between regulations and labour market outcomes is more complex because the majority of workers are located either in the agricultural sector or the urban informal economy. Moreover, enforcement of regulations is weak due to such factors as insufficient labour inspection and corruption. At the same time, it is often argued by economists that these labour market regulations are a driver of informality: enterprises would rather remain unlicensed and unregistered to avoid punitive labour laws that would require them to adhere to such conditions as the minimum wage and severance pay.

During the global financial crisis, labour market regulations have received new interest among certain commentators (such as the International Labour Organization) in terms of their role in mitigating the shock emanating from the trade collapse and credit crunch. For example, in many European countries, protection from dismissal (and the associated severance pay and other indirect costs) encouraged employers to adjust to the shock through internal mechanisms, namely working hours, before firing workers, which was the main channel of adjustment in countries with weak protection such as the United States. In emerging economies, there has been a stronger focus on the role of minimum wages in protecting the incomes of the poor during the global financial crisis; in this respect, Brazil raised the minimum wage over recent years, helping reduce poverty and inequality despite the adverse economic downturn in 2009. In terms of the policy environment, the country chapters also discuss the role of social policies such as Bolsa Família in Brazil and the Child Support Grant in South Africa, because these (conditional and unconditional) transfers have become priority areas of intervention in emerging economies, and ultimately, have an impact on the labour market.

The framework presented in Figure 1.1, which stresses the inter-linkages between longer-term labour market challenges, the impact of the global financial crisis and the role of labour market regulations, therefore, forms the overriding storyline for this book. The discussion and insights are strengthened by an in-depth examination of the aggregate trends (also disaggregated by gender, education and other factors) and micro-econometric analysis utilizing unit-level data, which allows for the identification of the role of specific factors, such as education, in driving labour market outcomes.

The remainder of this book centres on two segments: Part I provides a comparative perspective on labour market trends (Chapter 2) and labour market policies and institutions (Chapter 3), which allows for an overview of these issues across a number of emerging economies. Part II consists of the four country chapters on Brazil (Chapter 4), Indonesia (Chapter 5), South Africa (Chapter 6) and Turkey (Chapter 7), which all address the troika displayed in Figure 1.1 to varying degrees. It should be stressed that the emphasis in these country chapters is not the same; rather, the aim is to highlight the diversity in the labour markets of these emerging economies, though building from a common framework. In order to find more robust and deeper insights on these relationships, all of the country chapters turn to the unit-level data to estimate simple but highly relevant micro-econometric models that supplement the analysis of aggregate data in the comparative chapters.

Chapter highlights

Part I

Chapter 2: Labour Market Trends in Emerging Economies: Resilience versus Decent Work Deficits

While there is wide acceptance that consistently strong economic growth is a necessary condition to make major inroads into reducing poverty, less thought has been given to how this expansion in economic activity has translated into labour market outcomes in emerging economies. In this regard, high rates of economic growth have been witnessed in Indonesia and Brazil (prior to the 2000s). China has more recently emerged as the leading growth centre of the world, while India has begun to stake a claim at being part of this elite group of countries. Countries like Turkey have shown a new era of resilience in the face of the crisis and strong economic prospects. However, despite robust economic progress in emerging economies, and in most cases, falling rates of poverty, the labour markets of these countries have not always benefited to the same extent. In particular, informality, working poverty and vulnerable employment continue to be the norm for most workers. At the same time, women, youth and other segments of the population face hurdles to accessing the few good jobs in the formal economy.

For this reason, unemployment is typically not the best indicator of slack and distress in these labour markets. More importantly, the labour markets in emerging economies continue to be characterized by strong segmentation between a small formal sector and large informal sector. Many people continue to live in rural areas and rely on small household plots and subsistence farming, while an increasing number have left for urban areas and to seek their fortunes in other countries. Another common feature is ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Box

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- 1. Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Index