- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

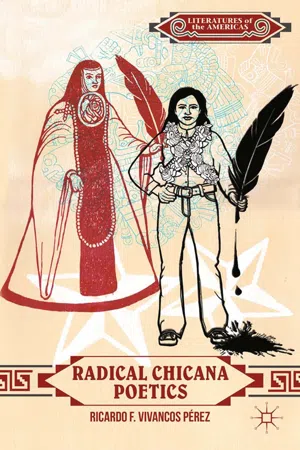

Radical Chicana Poetics

About this book

Offering a transdisciplinary analysis of works by Gloria Anzaldúa, Cherríe Moraga, Ana Castillo, Emma Pérez, Alicia Gaspar de Alba, and Sandra Cisneros, this book explores how radical Chicanas deal with tensions that arise from their focus on the body, desire, and writing.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Dangerous Bodies/Texts

Juncture ●

Polycentricity

In Part 4 of the prose section of Borderlands/La Frontera, the Aztec goddess Coatlicue is an archetype in the Jungian sense, a “presence” in the narrator’s psyche: “For me, la Coatlicue is the consuming internal whirlwind, the symbol of the underground aspects of the psyche” (Borderlands 68). Coatlicue “lives” inside the narrative persona’s inner self together with other myths of Chicanas’ particular pantheon of diosas:

I’ve always been aware that there is a greater power than the conscious I. That power is my inner self, the entity that is the sum total of all my reincarnations, the godwoman in me I call Antigua, mi diosa, the divine within, Coatlicue-Cihuacoatl-Tlazoleotl-Tonantzin-Coatlalopeuh-Guadalupe – they are one. (Borderlands 72)

In a footnote, Anzaldúa acknowledges that she is following James Hillman’s Re-Visioning Psychology (1976). Hillman’s “polycentric” and “polytheistic” view of personality—what he later called “archetypal psychology”—is a main source for Anzaldúa’s spiritual and mythical understanding of the “New Mestiza consciousness” in Borderlands. A close look into Hillman’s notions about “personifying” and “imagining things” not only discloses how influential his 1976 book was for Anzaldúa, but also reveals how archetypal psychology has remained at the core of subsequent radical Chicanas’ theoretical quests to find “fantasy images” of their psyches, and to make them part of their polycentric figurations of themselves.

For Hillman, “personifying is . . . both a way of psychological experience and a method for grasping and ordering that experience” (Hillman 37–8). His Jungian approach to psychology favors the use of images and metaphors instead of bare abstract concepts. In Hillman’s thought, myths and archetypes become “recognizable as persons” within our psyche. They are “guiding spirits . . . with ethical positions, instinctual reactions, modes of thought and speech, and claims upon feelings. These persons, by governing my complexes, govern my life. My life is a diversity of relationships with them” (35). Polycentricity “means recognizing our concrete existence as metaphors, as mythic enactments” (157). The procedure, following Hillman, starts with dealing with “the little people,” the daimones or archetypal persons that represent what Jung calls Shadow, Self, Ego, and Anima.

In her search for a method of differential consciousness and spiritual transformation, Anzaldúa proposes, as point of departure, to establish a dialogue with the personified images and metaphors inside one’s inner self, and to acknowledge our “relationship” with them as “living psychic subjects” (Hillman 32). Our individual consciousness is shaped by our internal relationship with many “reincarnations.” Only by dealing with how personified images and metaphors “govern” their inner selves can Chicanas and border subjects give an account of themselves, start addressing their oppression, and initiate emancipatory actions. At the level of collective consciousness, Anzaldúa intends to preserve individual differences in the processes of coalition politics. As I explained in the Introduction, by conceiving “Chicana” as a polycentric subject position, in the early 1980s Anzaldúa stands out against an earlier ethnonationalistic understanding of Chicano identity, and rejects views that promote the erasure of internal differences.

In its early stages, Anzaldúa’s method is strikingly similar to Hillman’s. She argues that Chicanas and Chicanos need to return to Aztec cosmology following Hillman’s return to Hellenism as the ancient culture that best represents polytheistic psychology and identity. If we read the section in Hillman’s book on “returning to Greece” through Anzaldúa’s indigenist eye, changing “Hellenism” for “Aztec thought” or “Aztec culture,” we can appreciate one of her strategies in the process of conceiving Borderlands and her early dangerous beasts poetics:

Hellenism [Aztec culture], however, brings the tradition of the unconscious imagination; Greek [Aztec] polytheistic complexity bespeaks our complicated and unknown psychic situations. Hellenism [Aztec thought] furthers revival by offering wider space and another sort of blessing to the full range of images, feelings, and peculiar moralities that are our actual psychic nature. They need no deliverance from evil if they are not imagined to the evil in the first place

. . . Greece [Aztec civilization] provides a polycentric pattern of the most richly elaborated polytheism of all cultures, and so is able to hold the chaos of the secondary personalities and autonomous impulses of a field, a time or an individual. The fantastic variety offers the psyche manifold fantasies for reflecting its many possibilities. (Hillman 28–9)

Anzaldúa mentions Hillman in an early interview in 1982 when she explains what she understands as “a writing of convergence.” In his study of Renaissance theories on the “anima,” Hillman defines “Gloria duplex” as the capacity of having “more than one standpoint, seeing behind, seeing through, and hearing the many voices of the soul” (Hillman 211). Anzaldúa adapts this idea to her early philosophical system: “I gave it a name. I called it the ‘Gloria Multiplex’ because I thought I was multiple.” Multiplicity provided her with “the point of view of looking at things from different perspectives” in the process of writing (Anzaldúa, Interviews/Entrevistas 37).

There are evident intertextualities between Hillman’s and Anzaldúa’s books, but what attracted Anzaldúa the most was the subversive component of Hillman’s approach to consciousness or “soul-making.” Hillman rejects the pathologization of “schizoid polycentricity.” Instead, he argues for accepting its working within the individual’s psyche. A polycentric personality is not necessarily a disease, and can be turned into our own advantage. Dissociation may be acknowledged and used as a positive force:

The phenomena of dissociation—breaking away, splitting off, personification, multiplication, ambivalence—will always seem an illness to the ego as it has become to be defined. But if we take the context of the psychic field as a whole, these fragmenting phenomena may be understood as reassertions against central authority by the individuality of the parts. (Hillman 25)

Anzaldúa and most radical Chicanas embraced this understanding of psychology to create their poetics. Dissociation and everything that comes with it—mainly displacement, personification, multiplication, and ambivalence—need to be considered as essential elements of difference. They all have a potential to empower Chicanas and atravesados.

Despite being generally overlooked, Hillman’s influence on Anzaldúa helps us clarify how she and radical Chicanas envision their figurations of themselves as dangerous beasts, and how they incorporate the mythical and the spiritual as part of the political. Their polytheistic and polycentric approach to consciousness awareness is crucial to understand the way Chicana thinkers create figurations of themselves as Chicana writers. The mythopoetic multiple selves included in their texts are particular political fictions that focus on the body and sexuality without losing track of the mythical and the spiritual, figuring out one’s own in-between states, and developing what she defines as “facultad,” or ability to see “beyond” surface phenomena.

Regarding dangerous beasts poetics, what interests us is how Hillman inspired Anzaldúa’s thoughts on “a writing of convergence.” Hillman defines “schizoid polycentricity” as a style of consciousness: “This style thrives in plural meanings, in cryptic double talk, in escaping definitions, in not taking heroic committed stances, in ambisexuality, in psychically detached and separate body parts” (Hillman 35). His method implies a set of questions regarding our relationship with our myths and archetypes:

Where are they located? Are they knowable—if so by what means, and how can we “prove” their existence? What is their origin? How many are there, and how do they form hierarchies and subclasses? Do they change or age or go through history? What sort of “body” do they have? How soon a psychology of archetypes begins to sound like a mythology of gods! (Hillman 36)

These are questions that Chicana thinkers began incorporating into their search for emancipatory methodologies since the 1980s, and were added to more general ones in the construction of “Chicana” as a polycentric subject position: What is “Chicana”? How can the story Chicana be narrativized collectively? How can the individual and the collective be conciliated in the construction of “Chicana”? How can we include and amalgamate all experiences without erasing internal differences?

Anzaldúa’s thought evolved substantially since the publication of Borderlands. Her early conception of her mission as a writer is, as she said in the 1982 interview, “to connect people to their reality—their spiritual, economic, material reality, to connect people to their past roots, their ancient cultures” (Anzaldúa, Interviews/Entrevistas 36). These initial thoughts, which focused more on adding Aztec cosmology into her method, were refined throughout her career in a zigzagging movement between abstraction and actualization, while always aiming for contingent synthesis and clarity. In her latest views on her task as a writer, she will consider writing simply as “compromiso to create meaning, something new” (Anzaldúa, “Putting” 92), in order to “leave a discernible mark on the world” (Anzaldúa, “When I Write I Hover” 238). However, her understanding of consciousness remained faithful to Hillman’s. For him, consciousness “seeps in through mystical participation in a processional of personifications, interfused, enthusiastic, suggestible, labile” (Hillman 35). For Anzaldúa, “New Mestiza consciousness” includes this “processional of personifications” and the same interaction, passion, suggestibility, and continuous change that Hillman describes. For radical Chicanas, creating powerful polycentric figurations and reappropriating dissociation as a potentially positive force are, since the 1980s, essential operations in the construction of dangerous beasts poetics.

Chapter 1

Gloria Anzaldúa’s Poetics: The Process of Writing Borderlands/La Frontera

Art and theory aggrandize each other.

—Gloria Anzaldúa, unpublished manuscript

After its publication in 1987, Gloria Anzaldúa gradually became aware that Borderlands/La Frontera was on its way to be the single, most influential book written by a Chicana. For the rest of her life, she was concerned that her only full-length published book was misinterpreted, and that her thoughts were considered categorical, or inaccessible to larger audiences. However, most of all, she was worried that people did not understand that her book was part of a life-long project. Borderlands represented the most crucial step in her ongoing search for a method, but nonetheless just one stage in the ongoing (re)formulation of her work. That is why immediately after the publication of the book, she was already revising its contents, polishing and reshuffling her ideas.

Anzaldúa’s writings need to be approached as an organic whole. Her thought is performative and contingent, and emerges as a continuum of accumulations, reformulations, additions, and provisional syntheses. This process becomes a personal quest that is both aesthetic and theoretical, on the one hand. On the other, it becomes a political intervention that aspires to be part of a collective ideological struggle. In her works, both aspects—the personal and the political—are shaped by metapoetic reflections. The evolvement of her thought can be followed mostly in what she called “autohistoria-teorías,” or “personal essays that theorize” (Anzaldúa, “now let us shift” 578). However, some of her essential theorizations are to be found in her published interviews and drawings, as well as in other precious unpublished materials held at the Benson Library in the University of Texas at Austin.

Anzaldúa is a metapoetic writer. Writing and how to write are essential preoccupations shaping her poetics. When she states that “writing is one way of constructing identity” (Anzaldúa, “To(o) Queer” 272), she is addressing both her position as spokesperson for Chicanas and atravesados, and her occupation and mission as a writer. Her published and unpublished materials show how passionate and determined she was to incorporate a discourse on writing—metastories about being a writer and about her writing experience—into her own process of identity formation. The incredible amount of work dedicated to drafting and polishing her texts, as well as the large amount of unpublished materials that she left are indicative of her obsessive perfectionism and her ambition, both politically and aesthetically.1 The writer, as she explains in Borderlands, is a healer, and a shaman. Her position as leading intellectual is therefore that of the nahual or “shape changer,” understood as a figure capable of transforming oneself, others, and discourses.

In 2002, two years before her untimely death, Anzaldúa wrote in her journal her own self-definition: “shortestbioGEA: Feministvisionaryspiritualactivistpoet-philosopher fiction writer” (Anzaldúa, Gloria 3). More than anything else, she considered herself a “poet-philosopher fiction writer.” The rest of her self-definition comes as a one-word modifier that accounts for, one could say, ideological qualities added to the core of her identity as a poet-philosopher. If Anzaldúa considered herself, first and foremost, a writer, why shouldn’t we consider her occupation and vocation as one main point of entry into the study of her works? If Anzaldúa represents the first generation of Chicanas with prominent academic influence, why shouldn’t we tackle the implications of this achievement in our analysis of her thought?

AnaLouise Keating and several others complain that Anzaldúa’s work after Borderlands has been understudied, and that her contribution to feminist thought, Queer studies, and Border studies is much wider than what academics have shown. In this vein, recent works have expanded Anzaldúan studies by dealing with the intersec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Disclaimer, Captatio Malevolentiae, or Are Nos/otros Ready to Move On?

- A Note about Language, Terminology, and Structure

- Introduction Fearing the “Dangerous Beasts”: Radical Chicana Poetics

- Part I Dangerous Bodies/Texts

- Part II (Re)Positionings

- Part III Global Interventions

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Radical Chicana Poetics by Kenneth A. Loparo,Ricardo F. Vivancos Pérez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.