eBook - ePub

The Democratic Transition of Post-Communist Europe

In the Shadow of Communist Differences and Uneven EUropeanisation

M. Petrovic

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Democratic Transition of Post-Communist Europe

In the Shadow of Communist Differences and Uneven EUropeanisation

M. Petrovic

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Tracing both economic and political developments through the prism of history as well as more recent developments, this book casts new light on the role of communist history in setting the different regional successes in post-communist transition.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Democratic Transition of Post-Communist Europe by M. Petrovic in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Socio-Economic and Political Facts on Post-Communist Transition

1.1. The necessity for and uneven distribution of foreign assistance

The experience of more than twenty years of post-communist development in East Central and Eastern Europe shows that transitional reforms have been introduced and implemented in all countries in the region as a similarly structured and simultaneous process of integral political, economic and, in some cases, territorial or state transformation. While in virtually all of these countries the communist political monopoly was replaced by the introduction of institutions of multi-party democracy within a period of less than three years, from February 1989 to October 1991 (see Chapter 4), the consolidation of the work of these institutions and especially the introduction and implementation of market reforms needed much more time and resources.1 The other important similarity shared among the ex-communist countries at the beginning of their post-communist history related to a serious lack of local knowledge and more importantly a lack of resources for modelling and financing the construction of the necessary institutional frameworks for the introduction and operation of a multi-party democracy and market economy. The 40-year-long period of intensive communist institutional, educational and ideological “re-building” as well as the use of extremely inefficient non-market mechanisms of economic coordination in the “development of socialist economies” affected very similarly the individual (in)capacity of all East European countries to undergo the process of post-communist democratisation and economic marketisation.

The only two partial exceptions to this seem to have been Hungary and Yugoslavia, as the only two European communist countries that had completely abandoned the centrally planned mechanism and experimented with a “socialist market economy” (Lavigne, 1999, Chapters 1 and 3; Swain and Swain, 2003, Chapter 6), which provided economic and managerial elites with a general knowledge of core concepts behind the functioning of a market economy. The Yugoslav “self-managed” economic model, which allowed open and relatively extensive trade, business, scientific, cultural and tourist relations and exchanges with the West, seemed to be particularly advantageous in this regard (Batt, 2004; Woodward, 1995).

In contrast to the other East European economies, the Yugoslav and to a lesser extent the Hungarian economies were not only relatively open to the West but also operated a relatively strong private agricultural sector, which provided relatively cheap food supply for the two nations as well as export surpluses. Furthermore, operation of small private firms in trade, the personal service sector and tourism were strongly encouraged by the governments of both countries (especially from the late 1970s), while the self-managed system in Yugoslavia enabled its “socially owned” firms to establish trade and business relations with Western partners with much less interference by the government and political establishment than in any other East European communist country. The Yugoslav economy and its people thus came into contact with, and later took possession of, valuable modern (Western) technology and expertise, including that of the real meaning of basic market concepts such as established prices, credit obligations and interest rates in everyday economic and business life, which was basically unknown in the communist world of centrally planned economies. However, the Yugoslav and Hungarian “market” economies, as “socialist” ones,2 were fundamentally incomplete and defective, based on a “social” (i.e. state) ownership, instead on private ownership, and neither – following the communist ideological insistence on the sacredness of the right to work as a basic “democratic right in socialism” – allowed the bankruptcy of inefficient firms or redundancies. These political predispositions that were imposed on the functioning of these two reformed “socialist (market) economies” made them hardly less inefficient than “traditional” centrally planned economies in other communist countries (Lampe, 1996: esp. 308–320; Lavigne, 1999: 25–27; Petrović, 1995).

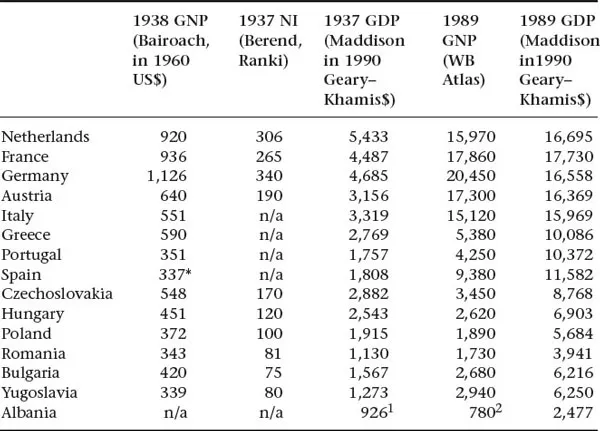

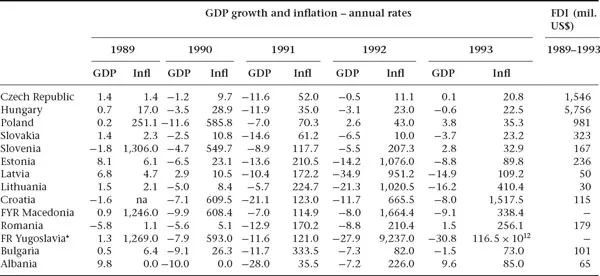

As can be seen from Table 1.1, the above-noted advantages of the Yugoslav and Hungarian economies had very little effect on these countries’ general economic performance during their communist history. In this regard, the differences between these two and the other European communist countries were insubstantial, with the exception of the economically very backward Romania and Albania, whereas the gap with the Western world increased enormously. Even (by Western standards) the less developed countries of Southern Europe – Greece, Spain and Portugal – which had a lower Gross National Product (GNP) per capita than Czechoslovakia and slightly higher or lower GNP per capita than the other European communist countries before the Second World War – had achieved a much higher GNP per capita by 1989 than all European communist states (see also Greskovits, 2000; Sachs and Warner, 1996). With such an economic legacy of communism none of the post-communist states in Europe, either from East Central, North-Eastern (Baltics) or South-Eastern (Balkans) Europe, could have provided any superior material base for financing the costs of post-communist reforms. The economic crash that affected all transition countries – with no exceptions – in the first years after the collapse of the communist regimes (Table 1.2) further highlighted the need for and reliance and dependency of these countries on foreign assistance in conducting successful post-communist transition.

Table 1.1 Gross National/Domestic Product or income per capita in Central, South and South-Eastern Europe and some Western European countries (in US dollars)

*$403 in 1933.

1data for 1929.

2data from WB Atlas electronic edition.

Sources: 1937/38 data: Bairoch (1976); Berend and Ranki (1974); Maddison (2006). 1989 data: World Bank (1991); Maddison (2006).

Faced with a lack of local knowledge and more importantly a lack of resources for modelling and financing the construction of the necessary institutional framework for introduction and operation of the desired systems of multi-party democracy and market economy and its accompanying net of welfare services, the governments of the newly democratised states were forced from the very beginning of their transition attempts to rely on Western advice and even more so on their financial support. This advice and help has come, more or less uniformly for all “applicants”, in the form of economic policy and structural change packages created in accordance with the neo-liberal spirit of the so-called “Washington consensus”, the strict implementation of which paradoxically led to a further deepening of the economic crisis in transitional states during their first post-communist years.3 Along with Western economic advice and financial support also came political requirements, including the basic insistence on political democratisation and respect for human and minority rights along desirable patterns of more specific social relations and cultural priorities as defined by the major financiers (i.e. creditors and donators) of transitory reforms in Eastern Europe (Janos, 2001: 236; see also Melich, 2000). Although the importance of the bilateral arrangements, particularly those made with the United States, as the “world’s only remaining superpower”, should not be underestimated, the role of international organisations and financial institutions has been crucial in defining these requirements; this becomes particularly relevant when examining the roles of the IMF, the World Bank, the EU and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) – which was founded with the exclusive purpose of supporting economic transition in the post-communist countries.

Table 1.2 Growth in real GDP, inflation and FDI inflow in East European states, 1989–1993

*Serbia and Montenegro.

Source: EBRD Transition Report, 2001: 59, 61, 68.

Under these circumstances, transitional countries were anything but free to design and implement necessary reforms on their own terms. The eventual choice of a “right or wrong” transitional model could not have been the reason for attributing an advantage or disadvantage to any group of East European nations in completing the tasks of post-communist transition. As the basic political reforms were accomplished primarily according to Western European patterns and the pre-communist traditions of individual countries in virtually all European ex-communist countries, including initially even those later affected by the eruption of civil/ethnic wars “with impressive ease and efficiency” (Crampton, 1997: 420),4 the success of the “entire project” of post-communist transition has become primarily dependent on success in economic reform and the closely related consolidation of newly founded democratic institutions.5 Apart from some differences in the “sequencing” of speed and methods of conducting particular stages of reform among the individual countries (Roland, 2002), the questions of whether and when a country commenced substantial reforms of its economic systems as a consequence of the ability and willingness of ruling governments to reform socio-political and economic systems in accordance with the requirements imposed by the Western “financiers of transition” have in fact made the real difference among the transition states.

1.2. The decisive importance of EU assistance

The above-elaborated characteristics of the general socio-economic conditions in which the post-communist states of East Central and Eastern Europe entered the process of painful economic transition from a centrally planned to a market economy and the complex process of the consolidation of the working of the relatively quickly established (basic) institution of democracy clearly indicate that those states that were able to re-establish closer political and economic ties with Western countries had greater prospects for success in post-communist reform. The closer to the moment of the beginning of transition, i.e. the collapse of the communist regime and the deeper these ties were re-established, the greater were the chances of particular countries to receive greater assistance and introduce faster and more easily necessary reforms. A particular advantage over their ex-communist counterparts had those post-communist states which succeeded to open the process of association and (later) accession to the EU. This came about not only because of the amount of financial and economic assistance and aid they received from the West and the EU in particular6 but especially because of the invaluable guidelines and assistance in expertise that they received from the EU (mostly through and within the accession and pre-accession process) in building new institutions of democracy and a market economy on their institutional “tabula rasa of 1989” (Elster et al., 1998: 25). The latter came in the form of an obligation by the applicants to fully comply with the established “conditions for accession” – in particular, the 31 “acquis communautaire”, which have practically defined the complete legal and institutional framework for the functioning of the economic and socio-political systems in the EU candidate countries and which were the focus of accession negotiations with each candidate. Although often criticised for being too detailed, bureaucratic and patronising, with scant regard for specific domestic conditions and democratic procedures within each candidate country (Dimitrova, 2002; Grzymala-Busse and Innes, 2003; Raik, 2004), the EU’s accession requirement for the fulfilment of the acquis criteria was actually the only viable option...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Foreword by Richard J. Crampton

- Acknowledgements

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. Socio-Economic and Political Facts on Post-Communist Transition

- 2. Critique of the Existing Explanations

- 3. Differing Aspects of Communism

- 4. Differing Regime Changes and Outcomes, 1989–2004

- 5. The Changed EU Approach – New Challenges for the Western Balkan States after 2005?

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index