This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Chinese State, Oil and Energy Security

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Monique Taylor analyses the policy rationale and institutional underpinnings of China's state-led or neomercantilist oil strategy, and its development, set against the wider context of economic transformation as the country transitions from a centrally planned to market economy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Chinese State, Oil and Energy Security by Monique Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economía & Política económica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EconomíaSubtopic

Política económica1

A Party-State Centred Explanation of Policymaking in China’s Oil Sector

This volume traces the development of China’s state-led oil strategy, which is frequently referred to in the extant literature as ‘neomercantilist’ in orientation. This statist strategy is in contrast with a liberal market-led approach to energy security, which relies on markets to allocate oil resources and prescribes only a minimalist facilitator role for the state. China’s state-led oil policies entail the use of top-down party-state authority and control in order to undertake domestic and international oil production for the purpose of ensuring a secure, stable and affordable oil supply. The central party-state’s institutional capacities and policy instruments, such as national oil companies (NOCs) and central planning agencies, enable Beijing to pursue this statist approach. In explaining China’s oil policy rationale and implementation, this study provides a historical analysis of party-state institutions and the Chinese policy process. In doing so, it shows that the central party-state has, in recent years, expanded and strengthened the political, organisational and fiscal capacities that permit it to exert centralised, top-down authority, while at the same time retaining the incentives and dynamism that were created through decentralisation of the market-oriented players during the earlier stages of oil industry development. This party-state centred explanation of institutional change relies on historical narrative to show how state capacities in the oil sector have been accumulated, built and improved over time. Where institutional change within this sector has occurred, usually at critical junctures in China’s economic development and market transition, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) elites have driven the process.

This argument runs counter to conventional accounts of China’s oil strategy, which are typically informed by an institutional approach to public policy analysis called fragmented authoritarianism (FA). Developed by Lieberthal and Oksenberg in the late 1980s, the FA model privileges the role of mid-level bureaucratic organisations in shaping policy outcomes in China. It broadly claims that the decentralised decision-making authority and fragmented structure that allegedly characterises the Chinese political system produces competition, conflict and extensive bargaining among various political actors, a dynamic that thwarts effective policy implementation (Lieberthal and Oksenberg 1988). The key findings of studies that rely on this particular theoretical understanding of the Chinese policy process as being disjointed and bogged down, tend to reveal a dysfunctional government and bureaucracy largely incapable of producing coordinated, coherent and effective energy policies (see for instance, Kong 2005, 2006 and 2010; Zha 2006; Downs 2004a, 2006 and 2008a; Lester and Steinfeld 2006 and 2007; Meidan et al. 2009; Yeo 2009a). According to this FA view China’s oil strategy is not state-led, but is instead the product of bottom or middle-up initiatives driven primarily by the NOCs (Downs 2006 and 2008a; Houser 2008; Jiang and Sinton 2011). The FA model was useful in explaining a particular period of policymaking in China, namely the decade of liberalisation and decentralisation that emerged with the onset of the Reform Era (‘reform and opening’, gaige kaifang) in 1978. This decade was characterised by a marked shift within the party-state from central command and control as well as Mao’s dictatorial rule, to more “horizontal interorganisational bargaining” (Bell and Feng 2013: 113).

While it remains useful in explaining bureaucratic authority in the post-Mao era, the FA model provides an incomplete understanding of policy dynamics and fails to account for the substantial change that China’s institutional landscape has undergone since the 1980s. FA also lends itself to the inaccurate, yet popular, view of China muddling through the Reform Era, ignoring the decisive, purposeful and reasonably successful actions of party-state leaders that have driven the reform process. This decisiveness has been especially evident since the early 1990s when significant recentralising and self-strengthening efforts were undertaken by Beijing in the aftermath of the Tiananmen protests and collapse of the Soviet Union and communist party-states in the Eastern Bloc (Yang 2004; Shambaugh 2008). The focus of the past decade in particular has been on building capacity in the ‘strategic sectors’ of China’s economy, such as the oil industry. The party leadership considers these strategic sectors vital to China’s economic growth and development, and social stability, and as such they were never intended to ‘grow out of the plan’ and eventually privatise, in contrast to the country’s non-state sectors (Naughton 1996).

Arguably now, more than ever, the central party-state is equipped to wield top-down authority and solicit compliance from various bureaucracies through a variety of CCP controls and career incentive structures within the nomenklatura system, which has been tightened in recent years and allows the party to determine senior personnel appointments throughout the state sector, and also through various monitoring mechanisms. The central government’s control over the banking system and oil pricing, as well as ownership of the NOCs, accounts for the significant power of the party-state to set policy for the oil industry. These centrally controlled political, organisational and financial instruments effectively counter the worst effects of bureaucratic fragmentation, hence mitigating some of the institutional shortcomings emphasised by the FA model. This is especially the case when a particular economic sector commands attention from the top leadership, which is what happened to the oil industry from roughly 2003 onwards. The centralised and pervasive power of the CCP is a particularly significant yet largely neglected variable, and is one that is increasingly advanced by a handful of scholars such as Naughton (2008a), Bell and Feng (2009 and 2013), Pearson (2007) and Shambaugh (2008) as being fundamental to understanding policymaking in China. In this study ‘bureaucratic authoritarianism’ (BA) is advanced as a more appropriate model since it provides an elite-driven account of institutional change and top-down policymaking by emphasising “the rise of bargaining within a hierarchical state system” (Bell and Feng 2013: 115).

At various stages of China’s economic development the CCP leadership has clearly demonstrated its capacity to reach in, reorganise and restructure the Chinese state. Since the FA model provides a static description of how the state apparatus functions, it struggles to explain how institutional change has occurred within the party-state. Furthermore, in bracketing the influence of elite power, this model certainly does not perceive the significance of the CCP in effecting institutional change. While political authority in the oil sector is primarily a top-down phenomenon, the relationship between the central party-state and the NOCs is reciprocal in the sense that the oil companies are granted space to advise policymakers by virtue of the fact that they are repositories of specialised knowledge and expertise, and possess strong informal connections to party-state leaders. This dynamic has led Kong (2010: 27–28) to suggest that China’s oil policy is shaped by the central government and the NOCs’ ‘co-governance’ of the oil industry, which implies that both actors have equal decision-making input. However, a close examination of the interplay between elite and bureaucratic power within the party-state shows that the Chinese leadership remains the pivotal and decisive player that ultimately chooses policy content and determines strategic direction for the oil industry. As such it is the steep hierarchy of authority within the central party-state that governs this collaboration between the Chinese government and the NOCs.

Central party-state capacities were strengthened and have expanded since the early 1990s, resulting in the emergence of a clearer energy security agenda and blueprint for economic and industrial development within the strategic sectors of China’s economy. The capacity of the party leadership to drive reform and institutional change is the central dynamic shaping oil industry development. This study explores governance arrangements within this strategic sector, how they impact energy policy articulation and implementation, and ultimately how this is reflected in China’s domestic and international energy behaviour with respect to both upstream and downstream oil activities. Analysing these various facets of policymaking in China’s oil sector involves exploration of the policy orientation and central directives espoused by the leadership of the CCP (who determine the overarching framework of China’s energy policy, laid out explicitly in the government’s Five-Year Plans and other policy documents), and how these have been implemented by key party-state bureaucracies including the State Council, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the newly formed National Energy Commission (NEC) and its standing body – the National Energy Administration (NEA), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), the Ministry of Finance (MOF), the Export-Import Bank of China (China Eximbank), the China Development Bank (CDB), the State Asset Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) and, most importantly, the NOCs – China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), China Petrochemical Corporation (Sinopec Group), China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and Sinochem Group (Sinochem).

China’s oil security dilemma

China’s role as a major driver of world oil demand growth over the past decade has generated apprehension, even alarm, among other oil consuming countries, notably the United States and Japan. Here the concern does not simply revolve around China’s ever-increasing oil requirements to fuel its rapidly expanding economy, nor its newly-acquired status as the world’s largest energy consumer and second largest oil consumer and importer behind the United States (despite the fact that it is the fourth largest oil producer) (People’s Daily 2010b; IEA 2007: 265; IEA 2010), but also the perceived manner in which the country seeks to achieve energy security, through both its domestic and international oil activities. For instance, whilst the official rhetoric espoused by the Chinese leadership favours increased marketisation, China’s oil sector remains under tight state control and entails a regime of price controls and subsidies. This encourages the inefficient allocation and excessive consumption of oil, thus maintaining domestic demand at artificially high levels when world oil prices are high, which was evident during the oil shock of 2007–2008. On the international stage China’s preference for long-term bilateral oil supply contracts (termed equity oil) with oil-producing countries, which allegedly ‘lock up’ foreign oil supplies, may be considered a threat to the effective functioning of world oil markets, and the competitiveness of other NOCs and international oil companies (IOCs), as well as to the energy security of other oil importers (Pei 2006a). Other aspects of China’s statist oil strategy, including the extensive state-backed financial support and oil diplomacy used to augment the overseas investments of Chinese NOCs have also raised concerns among IOCs and oil consuming countries. Given current projections of China’s oil demand, worries surrounding its potential impact on oil affordability and accessibility may intensify over the coming decades. The IEA forecasts that China’s oil demand will account for the largest absolute increase in global oil demand growth through to 2035. It estimates that China will experience an average annual increase in oil demand of 2.2 per cent, with its consumption increasing from 9.0 mb/d in 2011 to 15.1 mb/d by 2035 (IEA 2012: 86). This increase would account for half the net increase in oil demand worldwide (IEA 2012: 86).

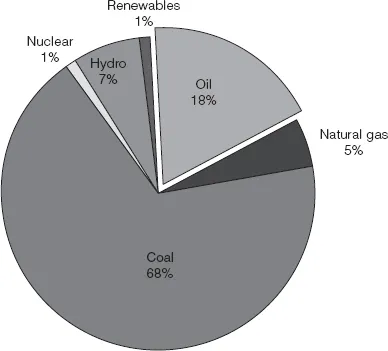

Dependency on imported crude oil accounted for 53.8 per cent of China’s total oil demand in 2010 (IEA 2012: 6). The 2010 edition of the IEA’s World Energy Outlook predicts that this oil import dependence is set to rise to 84 per cent by 2035. Within China’s energy mix oil remains less important than coal, comprising 18 per cent of total primary energy demand in 2012 (see Figure 1.1 for the composition of China’s energy consumption by fuel) (BP 2013). Demand for oil is the fastest growing component of China’s total energy demand, and poses the greatest energy security challenge for the country due to growing import dependency, world oil price volatility, strategic chokepoints in China’s oil supply routes such as the Strait of Malacca, political volatility in many oil-exporting countries and international competition for increasingly scarce oil resources. China’s domestic oil production has stagnated, especially in onshore crude oil-producing areas (most of these oil fields have already reached or passed their peak), and the ever-widening gap between China’s oil production and oil consumption must now be filled with imported oil. China’s NOCs, as latecomers to the global oil industry, have faced a steep learning curve and experienced some major setbacks in their pursuit of overseas mergers and acquisitions, a prime example being CNOOC’s thwarted attempt to purchase California-based Unocal in 2005. Hence China’s sharply increasing oil import dependency now occupies a central position on Beijing’s policy agenda, with Zheng Bijian (a lead thinker and advisor to the Chinese leadership) considering energy security to be the top policy challenge facing China (Chen 2011: 600). Energy policy is also intimately connected to social, economic, foreign and security policy, and has altered Beijing’s calculations of the national interest, as concerns about energy security, particularly conceived in terms of the dilemma of growing oil import dependency, appears to be an important factor that influences China’s perception of its external security environment and drives foreign policy (Zweig and Jianhai 2005; Ziegler 2006).

China’s demand for oil has been dictated by the nature of its economic development path and changing industrial profile. During the first twenty years of economic reform, from 1980 to 2000, economic growth in China was primarily dependent on light industry (mainly low-end manufacturing) and small-scale private enterprise. These industrial sectors are labour, rather than energy intensive. Hence while economic growth in this period occurred rapidly, energy efficiency gains were also apparent. From the early 2000s onwards, the Chinese economy’s energy intensity began to increase significantly. Breakneck economic growth, entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 (causing rapid growth in China’s trade volume, accelerating energy consumption), increasing urbanisation, motorisation and structural changes within China’s economy led to increases in China’s oil demand that far exceeded earlier predictions of energy demand growth. Indeed the boom in economic growth and the surge in the output of heavy industry from 2002 to 2005 in particular caught outside observers such as the IEA by surprise (Andrews-Speed 2011: 15–16). At this time the Chinese leadership shifted structural economic emphasis at the national level away from light industry and back toward heavy industry, which is highly energy intensive (Kahn and Yardley 2007). The reasons behind the shift towards heavy industry also dates back to 1997 when China’s leaders were concerned that the Chinese economy might suffer the same fate as other East Asian economies and enter recession in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis. In response Beijing put together an economic stimulus package, which provided “generous state financing and tax incentives to support industrialisation on a grand scale” (Kahn and Yardley 2007). It worked remarkably well. Kahn and Yardley (2007) note that in 1996 China and the United States each accounted for 13 per cent of global steel production, but by 2005 the United States’ share had dropped back to 8 per cent whilst China’s had risen to 35 per cent. China also manufactures around half of the world’s cement and glass and about a third of its aluminium (Kahn and Yardley 2007).

Figure 1.1 China’s Primary Energy Consumption in 2012 (2735.2 million tonnes oil equivalent)

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2013

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2013

Urbanisation in particular has caused heavy industry to grow as it creates demand for steel, cement and other industrial materials used to expand critical infrastructure and housing. In addition to the development of these energy intensive industries, a burgeoning consumer class and rapidly expanding civil aviation and car fleets further increase China’s appetite for oil. The transportation sector is now the principal driver of oil demand growth, alone accounting for one-third of China’s total oil consumption. China’s phenomenal motorisation boom has seen it become the world’s largest and fastest growing car market. Attempts to slow the addition of new cars on the road would be difficult at this stage of China’s modernisation as car ownership is symbolic and aspirational among Chinese consumers (Andrews-Speed 2011: 1), and is also an important “growth point” in domestic consumption, which the government is trying to stimulate (Cheng 2008: 310). Instead of trying to limit the increase of new cars on the road, Chinese authorities focus on improving fuel efficiency (Cheng 2008: 310). Hence the contemporary manifestation of China’s economy is highly energy intensive, with an ever-increasing reliance on oil.

China’s oil policy approach

Since the early 1990s China has undertaken a process of strategic adjustment in response to two major energy security challenges. The first challenge was growing oil import dependency, which began with the country’s shift from net oil exporter to net oil importer in 1993, ending thirty years of oil self-sufficiency. This move away from self-sufficiency also came at a time of rapid modernisation whereby the Chinese leadership was under tremendous pressure to deliver strong economic growth, thus exacerbating the perceived insecurity and vulnerability derived from foreign oil dependency (Yergin 2006: 77). The second challenge emerged a decade later with the hike in world oil prices beginning in 2003 and culminating in the oil shock of 2007–2008. In five years crude oil prices increased nearly 500 per cent, from roughly US$30 in 2003 to a record price of US$147 in July 2008. During this time the Chinese economy was also undergoing structural adjustment emphasising the development of heavy industries, which are of course energy-intensive, particularly in terms of fossil fuel consumption. This further heightened China’s energy crisis and catapulted oil security to the realm of high politics. Initially oil import dependency confronted the Chinese leadership with a new range of national security and geopolitical considerations, arising from the need to secure foreign oil supplies. However, in combination with inexorably rising oil prices, these concerns soon gave way to other systemic economic, industrial, social and political problems within the Chinese state, namely those relating to social equity and stability, industrial organisation and competitiveness and the need to maintain high economic growth rates. The deliverance of strong economic growth is of course the touchstone of CCP legitimacy and long-term survival, and secure, reliable and affordable sources of energy are fundamental to achieve this.

Faced with these energy security dilemmas Chinese authorities had several policy options from which to choose. Broadly, oil-importing countries can pursue either economic nationalist or liberal market approaches to the problem of energy security. Economic nationalists or neomercantilists, favour the concept of energy independence and define energy security in terms of the security of energy supply, which they seek to ensure through state-led energy production and distribution both at home and abroad (if self-sufficiency is unattainable), with foreign oil assets often secured through government-to-government contracts. Liberal market approaches, on the other hand, emphasise energy interdependence where global energy needs are satisfied via free market competition among domestic and international energy consumers. Here the market instrument requires little, if any, state involvement in the energy commodity chain. Ikenberry (1986: 113–116) identified a third approach of competitive accelerated adjustment, which targets the demand side of the energy equation through industrial competitiveness, for instance, by encouraging industrial energy efficiency and conservation with the aim of reducing national fossil fuel consumption. These three categories capture broad policy emphasis and approach. However it is important to recognise that energy policy is inherently complex and multifaceted and usually incorporates a variety of strategies in practice. China’s response to a range of exogenous and endogenous factors such as oil resource constraints, international oil price volatility and instability in oil-producing countries, broadly conforms to a state-led strategy (Kong 2005: 56; Zweig and Jianhai 2005; Zhao 2008: 207; Erickson and Collins 2007: 683), as Kong (2005: 56) neatly states: “Distrustful of the market, and suspicious of other major energy players in the international market, the Chinese leadership relies on the state-centred approach, or economic nationalism, rather than a market approach ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 A Party-State Centred Explanation of Policymaking in China’s Oil Sector

- 2 Sectoral Governance and State Capacity

- 3 The Interplay of Elite and Bureaucratic Power

- 4 The Socialist Era of Oil Self-Sufficiency (1949–1977)

- 5 Decentralisation and Corporatisation of the Oil Sector (1978–2002)

- 6 Rebuilding Oil State Capacity (2003–2013)

- 7 China’s National Oil Companies ‘Go Global’

- 8 Authoritarian State Capacity in a Liberal World Order

- Bibliography

- Index