This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Shakespeare and the French Borders of English

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This study emerges from an interdisciplinary conversation about the theory of translation and the role of foreign language in fiction and society. By analyzing Shakespeare's treatment of France, Saenger interrogates the cognitive borders of England - a border that was more dependent on languages and ideas than it was on governments and shorelines.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Shakespeare and the French Borders of English by Michael Saenger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Critique littéraire européenne. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LittératureSubtopic

Critique littéraire européenneCHAPTER 1

THE PLACE OF FRENCH IN ENGLAND

ONE OF THE MORE UNUSUAL METHODS OF THIS BOOK IS TO USE THE GRAPHIC TYPOGRAPHY OF NON-LITERARY BOOKS, particularly French primers, to provide insight into Shakespeare’s staging of England and France. Such an effort requires some methodological groundwork. By now, there is nothing particularly shocking about the idea of working across the anachronistic boundary that we now see between “literary” and “non-literary” texts, but the kind of work practiced in this study is relatively original, so the broad logic employed here needs to be clarified. This chapter addresses some fundamental aspects of this method, including the social history of London in relation to some of these books, as well as current trends in postcolonial, feminist and queer approaches to issues of interlinguistic contact. The goal of this chapter is to assess some of the problems scholars have encountered in using a postcolonial method to approach the Anglo-French relationship and to argue for a method that focuses in part on French primers and draws less from postcolonial theory and more from Lacanian concepts, economic criticism and feminist theory.

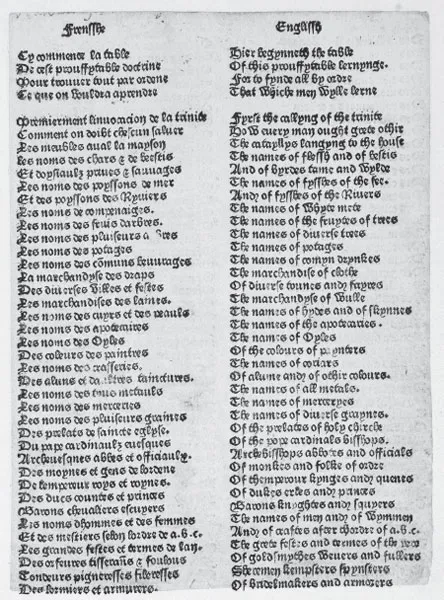

A review of some of the most important books that teach French would be helpful here; the textual conventions of these books offer a rich source for insight into how the French language and culture were processed in England. The history of printed books that instruct English people on how to speak French begins with the Vocabularius of William Caxton, published in 1480 (Figure 1.1). Caxton laid out French phrases and their English equivalents in facing columns, in the manner of his source text, a manuscript phrase-book in Flemish and French.1 Over the course of the sixteenth century, there were progressively more books printed offering language acquisition,2 and with this plenitude came a variety of different approaches. John Palsgrave’s Lesclarcissment de la langue francoyse (1530), followed by Robert Estienne’s quarto Dictionariolu[m] pueroru[m], tribus linguis Latina, Anglica & Gallica conscriptum (1552), represented relatively modest steps in popularizing French.

Figure 1.1 Caxton, William. Vocabularius, 1480, first page.

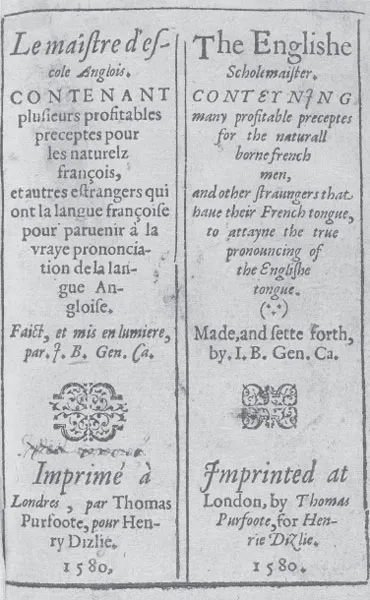

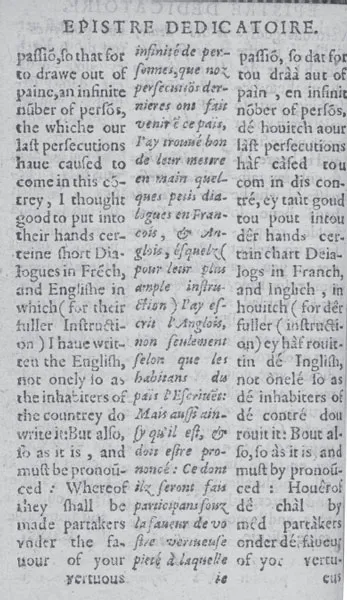

The proliferation of popular books of language instruction in quarto accelerates in the 1590s, abetted by the influx of Huguenots fleeing religious persecution into London. These migrants provided a French-speaking market for English merchants as well as a source of language instructors. By the time that Jacques Bellot’s The English Schoolmaster appears in 1580 (Figure 1.2), there is a strong market—on both the demand and supply sides—for teaching French to the English in London and English to the French in the same city, and the market develops codes attuned to the burgeoning commercialism of books. Jacques Bellot wrote three books of interest to this study. A Huguenot from Normandy, Bellot wrote The English Schoolmaster to help his fellow religious exiles learn English. He begins the book with an explanation of how to pronounce English orthography, which he approaches methodically. Following this, he presents a series of simple sentences with detailed explanation; he then includes a series of tables and miscellaneous texts that offer the reader a mixture of entertainment and instruction. Almost all the book is in double columns, and the primary goal is to teach a French emigrant to converse in English. The detailed attention Bellot pays to the way English letters are pronounced also means that his book could be used by a Frenchman who has acquired spoken English but wishes to learn how to read and write in his new tongue, as A. P. R. Howatt points out.3 Bellot’s 1586 primer, Familiar dialogues for the instruction of the[m], that be desirous to learne to speake English (Figure 1.3), is also a book that is designed to teach French speakers English, and he takes the phonetic emphasis even further, dividing his text into three columns. These are: English on the left, French in the middle and a transliterated English on the right. Because Bellot’s primary goal was to help French people function in England, this format makes sense. Here, he omits the more technical material of The English Schoolmaster and, instead, simply offers three-column text. The bulk of this book is about as miscellaneous as it could be, including not only the titular dialogues between various characters, but also the days of the week and the Lord’s Prayer.

Figure 1.2 Bellot, Jacques. The English Schoolmaster, 1580, title page.

In 1588, Bellot turned his attention in the reverse direction, offering a book to teach English speakers oral and written French with The French Methode, wherein is contained the perfite order of Grammer for the French Tongue. Interestingly, although Bellot defended the dignity of the English language in his books offering English skills, he spends much more effort on English pronunciation than on English grammar in those primers. By contrast, The French Method takes French grammar very seriously. Again, we get a wide array of texts. There are many exemplary texts in double columns, but there is also a great deal of explanatory text that bridges the columns. Certainly, the fact that French uses genders and inflections is part of the reason for this, but the book seems, in contrast with his English primers, to emphasize that French is to be learned correctly, with care. Although most of these books are overtly directed at one vector of language-learning, the chiastic character of the double-column page enables them to serve audiences whose native language is either English or French. In Bellot’s book English Schoolmaster, we see a double title-page (Figure 1.2), playfully advertising that the reader is buying a kind of linguistically parallactic book that will engender a bilingual vision.

Figure 1.3 Bellot, Jacques. Familiar dialogues for the instruction of the[m], that be desirous to learne to speake English, 1586, sig. [A2]v.

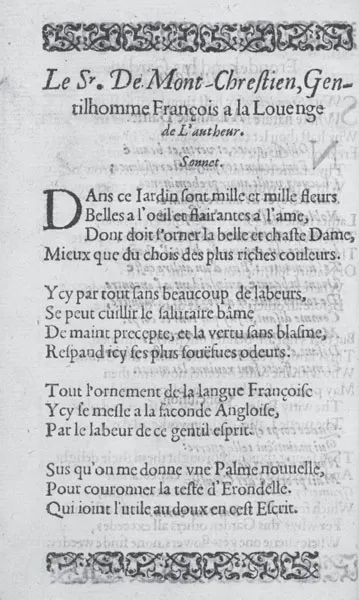

Peter Erondell, perhaps playing with this idea of multiple perspectives, titles his 1605 handbook The French garden: for English ladyes and gentlewomen to walke in. This book is not only limited to English people learning French, but indeed only women are welcome to read it. As I explore below, Juliet Fleming argues that this is a “cross-dressed” text, intended as much for women as for men who transgressively read it as they transgressively learn French. At any rate, the domestic, gendered scene imagined in the commendatory poem in Figure 1.4 (sig. [A6]r), from the prefatory material to this book, is a textual fiction regardless of the intended or actual gender of the reader. Erondell’s book itself consists of chapters on pronunciation and grammar followed by a fairly standard series of conversations, 13 in all, presented in double-column format. The grammar here is more simplified than Bellot’s exposition of the subject, and the weight of the book is devoted to French as a diversion—for whichever gender was reading it.

Claudius Hollyband wrote two books that are particularly relevant to this study. Hollyband, who also presented himself in a translated version of his name, as Claude Desainliens, was a Huguenot who escaped France in about 1564 and taught French in London, in addition to writing several popular French primers.4 His 1578 The French Littleton is presented as a book of instruction in Law French, but in fact, most of it is miscellaneous dialogues, and the final section is devoted to French grammar. The title alludes to Thomas Littleton’s Tenures, first published in circa 1482 and many times reprinted, which was an essential reference book for lawyers; Hollyband thus marketed his book as being equally essential to lawyers. While the primary target audience is thus English lawyers who lack sufficient French skills to practice their trade adequately, the book is easily useful to anyone seeking to learn French. A more specialized book on Law French, examined in the fourth chapter, is John Rastell’s An Exposition Of Certaine difficult and obscure words (1595). Rastell clearly presents this as a working glossary of words and concepts in Law French. This book would not be useful to an ordinary person seeking French skills, and it would probably not even be useful for a lawyer to prepare oral arguments; primarily, it is targeted at successfully reading and writing documents in Law French. The other book by Hollyband examined in this study is his 1583 Campo di Fior or else The Flourie Field of Foure Languages. The Campo di Fior is a four-column dialogue book with no grammar or vocabulary provided. On the title page of this book, Hollyband says that it is intended “For the furtherance of the learners of the Latine, French, English, but chieflie of the Italian tongue.” This book is printed in London and paratextually marketed to readers whose primary language is English, but it could well have been used, for example, by recent Continental émigrés to learn English. The four columns show equivalent meanings between each of the four languages noted. He divides the pages vertically and uses the facing pages of the book to work as one unit: we have the left verso in Italian, right verso in Latin, left recto in French and right recto in English. There is little evidence of particular emphasis on Italian, except for the title and the fact that there is more text in the Italian column than in the others. The fact that there is no grammar in this book, combined with the playful nature of the title, hints that this is a book of recreation more than a book of instruction.

Figure 1.4 Erondell, Peter. The French garden: for English ladyes and gentlewomen to walke in, 1605, sig. [A5]v.

John Eliot’s Ortho-epia Gallica. Eliot’s fruits for the French: enterlaced with a double new invention, which teacheth to speake truely, speedily and volubly the French-tongue (1593) is of particular interest here.5 It is divided into two “books.” The first contains some interesting prefatory text, addressed below, some rules of pronunciation and then three short dialogues. The “Rules for French pronounciation” are presented alphabetically, which might be a reasonable way to present vocabulary, but as a way of showing pronunciation, it makes for a chaotic page. It is often unclear whether Eliot is being satirical or not; that is, it is unclear whether he seeks to teach French, to satirize those who do so or to celebrate the French language and his own wit. It is probably safe to say that the book does all of these things. The title of the book means “The correct pronunciation of French” in Greek, but that is certainly not what this book offers. His conversation topics are clearly designed to allude to foreignness as a subject of irony and delight; the dialogues are called “The Scholler,” “The Tongues” and “The Traveller.” There does not seem to be any good pedagogical reason for ending the first “book” here. More than anything, the influence of Thomas Nashe comes through in this 1593 book, in the precarious and volatile satirical tone, the use of sharply contrasting order and chaos, as well as the bibliographical inventiveness. The second section, which he calls the second book, is entitled Ortho-epia Gallica, or, Le Parlement des Babillards: Id est: The Parlement of Pratlers. This section, in turn, is subdivided into a series of dialogues of a highly miscellaneous nature; this includes poetry, as discussed below. Most of the book is in double columns, but in places, such as on pages 63–64, he includes a three-column text, with a phonetic transcription of the French in the middle, French on the left and English on the right.

Of all the French primers, this is the probably the most difficult one to use to learn French, and yet that is exactly what Shakespeare did with it, probably because he found the stylistic variety of the text so engaging. Eliot’s was a book to which Shakespeare seems to have been repeatedly drawn; J. W. Lever finds echoes of Eliot in many of Shakespeare’s plays. Shakespeare even duplicates Eliot’s idiosyncratic mistakes; among many more subtle intertextual links, Lever adduces as a more concrete connection the fact that Shakespeare mistakenly uses “asture” in place of “à cette heure,” a peculiar error that he most likely drew from the fact that this was a typographical error in Eliot’s book.6 Joseph Porter writes that Ortho-epia Gallica “seems to have been a kind of pillow-book of Shakespeare’s, picked up and browsed in,”7 attracting him with “the vigorous unpredictability of good drama.”8 Frances Yates makes a plausible argument that Eliot’s book was meant to be read as a burlesque of other conversationally based primers, especially those of Florio and Hollyband, although she may be overstating the coherence of the book in this assessment. Lever locates the source for Gaunt’s famous speech in his essay:9 a French poem by Guillaume de Salluste du Bartas, first translated in Ortho-Epia Gallica. The intertextual link is clear enough when the Arden editor of Richard II prints Eliot’s text. Eliot’s “O France the mother of many conquering knights” becomes Gaunt’s “this England,/This nurse, this teeming womb of royal kings” (2.1.51). Eliot’s book was celebrated by critics of the first part of the twentieth century, in part because it is so delightful to read, and also because of a number of peculiarities; as Frederic Hard noted, it has an odd bibliographic construction. It also has the distinction of having had a famous owner: the copy of this book housed at The Huntington Library, photographed for this book, was owned, signed and commented upon by Gabriel Harvey.

There are a few obvious textual devices that shape identity formation in language-learning books—doubled naming, parallactic reading and incomprehensible text—and each of these techniques finds some corollary in dramatic texts. In language primers, these devices all engender a change in the reader, and thus also a change in how the book is read. For example, double-naming is used for things like an author’s or a patron’s name, which can be rendered in English and French; such double-naming points to an expansive model of Englishness. Parallactic reading, on the other hand, delivers a complicated experience. It can allow the reader to gain skills by using translatable columns to acquire vocabulary for later use; on the other hand, it can offer the reader something more like the feeling of interlinguistic fluency. Additionally, incomprehensible text can both advertise the fruits of learning and symbolize the distance between the reader and a conversation to which he is denied access. Finally, language primers often address a controversy familiar to language acquisition: which should come first, rules or action? All of these tropes can be linked to dramatic scenes, as this chapter shall demonstrate.

Before doing so, I survey recent work on interlinguicity with respect to Shakespeare, and I join a movement away from postcolonial theory. This movement away from postcolonial theory is typical for recent work, and I want to assess this trend and extend it to cover language primers as literary texts that provide important help in reading Shakespeare. I am not suggesting that language primers are unique; indeed, in the chapters that follow, I apply similar methods to reading a law textbook and a royal proclamation. My point is, indeed, to suggest that we examine interlinguistic texts in a continuum across a wide variety of genres. I suggest that language primers are an important part of the scene, a part th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- A Note on Typography

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The Place of French in England

- 2. Egoge and Verfremdung

- 3. Anterior Design: Presenting the Past in Richard II

- 4. Henry V and “Imaginary Puissance”

- 5. Comic Translations in All’s Well That Ends Well

- 6. “Dead for a ducat”: Tragedy and Marginal Risk

- Conclusion: “Am I in France?”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index