eBook - ePub

Communicable Diseases in Developing Countries

Stopping the global epidemics of HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria and Diarrhea

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Communicable Diseases in Developing Countries

Stopping the global epidemics of HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria and Diarrhea

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This books provides an essential study of communicable diseases, by integrating the diagnosis, treatment and cure of communicable diseases in developing countries with the practical aspects of delivery of these services to the public.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Communicable Diseases in Developing Countries by John Malcolm Dowling,Chin Fang Yap in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economía & Política económica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EconomíaSubtopic

Política económica1

Introduction

Health is the most significant determinant of well-being among developing country respondents in a recently published monograph by Dowling and Yap (2013). The book analyzes poverty and well-being in developing countries and reports a wide-ranging statistical analysis of the determinants of well-being in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The book draws on a database of surveys of respondents in these three regions conducted by the World Value Survey team over the past three decades. Drawing on this analysis, the current research explores the experience of developing countries in addressing the ongoing challenges of providing reliable and affordable healthcare. Particular reference is made to the contagious diseases of tuberculosis, malaria, Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and cholera, and related intestinal maladies such as diarrhea. In 2001, these four diseases accounted for the bulk of the disease burden facing developing countries, resulting in over 7.2 million fatalities each year (2.5 million from HIV/AIDS, 1.8 million from diarrheal diseases, 1.6 million from tuberculosis and 1.2 million from malaria) and countless years of suffering (Lopez et al., 2006). With the exception of HIV, the bulk of deaths were among infants and children under five years of age. By 2011, despite the recent advancements in healthcare, the fatalities faced were still close to five million each year in developing countries (out of which 1.6 million deaths were from HIV/AIDS, 1.8 million from diarrheal diseases, 0.8 million from tuberculosis and 0.6 million from malaria). According to the baseline scenario forecast for 2030, World Health Organisation (WHO) predicted that fatalities in developing countries due to HIV/AIDS and diarrheal diseases would remain around 1.7 and 1.5 million, respectively. There is a possibility of a decline in deaths from tuberculosis and malaria – to 0.5 and 0.3 million, respectively. It is to be noted that WHO has revised upward its 2030 estimates of total deaths from its original 2008 study, particularly that of fatalities due to diarrheal diseases.

A number of markers have been suggested to measure the progress that has been made in addressing the performance of health systems in countries around the world. Life expectancy, infant mortality and more aggregative measures such as the human development index of the United Nations (UN) have all been used as performance yardsticks. Other, more specific measures, such as the incidence of TB, malaria and HIV, have been developed to track more specific aspects of healthcare systems. Using life expectancy in years, global health has been tracked by economic historians and other researchers going back to the Middle Ages and even earlier.

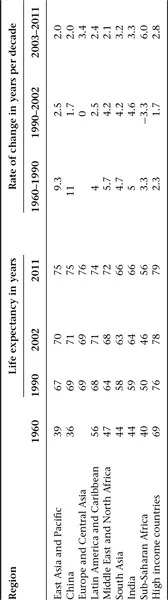

Data from antiquity and through the Middle Ages suggest that life expectancy did not increase with time, remaining at around 40 years of age or so through the Middle Ages. This was primarily because many died as infants or children. If one survived to become an adult, life expectancy was longer at about 50 years of age in the 15th and 16th centuries, and this didn’t change much until the late 18th and 19th centuries. With the advent of the industrial revolution, discoveries in medicine and technological developments, life expectancy began to increase in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries. By the dawn of the 21st century, life expectancy in Northern Europe and Japan approached 80 years and the rest of the industrial world was not far behind. Jamison et al. (2006) calculated that from around 1840 the maximum life expectancy increased by about two and a half years per decade for 160 years. Table 1.1 adopted from Jamison et al. shows that life expectancy continued to accelerate at a rate of four to nine years per decade, with China posting a whopping 11 years per decade between 1960 and 1990. However, not all countries and regions shared in this sustained increase in life expectancy. After World War II, the spread of diseases in Africa and Asia slowed the increase in life expectancy and introduced further roadblocks in raising health performance.

Progress in the developing regions of Latin America (four years per decade), South Asia (4.7 years per decade) and Sub-Saharan Africa (3.3 years per decade) was slower. In the following decade (1990–2002), the growth in life expectancy slowed further and even fell in Sub-Saharan Africa as a result of the spread of HIV/AIDS. Internal differentials in the delivery of health services within countries have also probably widened, although data are spotty. The hill tribe peoples in Southeast Asia and the poorer provinces in sections of India and inland China have been particularly affected, partly as a result of discrimination against minorities and also as a result of the continued concentration of medical personnel in urban areas. “Indigenous people everywhere probably lead far less healthy lives than do others in their respective countries.” (Jamison et al., p. 6). During 2003–2011, there were improvements in life expectancy, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, life expectancy for Sub-Saharan Africa still remains lowest among all the regions.

Table 1.1 Levels and changes in life expectancy, 1960–2011

Sources: Jamison et al. (2006, table 1.1) and World Bank (2013).

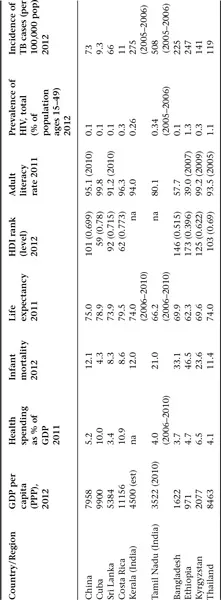

This is not to say that some of the less affluent countries have been unable to increase life expectancy and other health indicators to a level nearly comparable with countries that have very high levels of income. The 1985 Rockefeller Foundation published the study “Good Health at Low Cost” and presented the experiences of countries such as China, Sri Lanka, Costa Rica and the Indian State of Kerala as shining examples of how countries with fairly low income levels could achieve relative good health performance compared to their high income counterparts. Despite modest levels of per capita income and health spending as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Cuba and Costa Rica being exceptions with regard to health spending), they have attained life expectancy of 70 years and higher, literacy of over 90% as well as low levels of infant mortality and incidence of HIV and TB. Recently, a revisit of the same theme by Balabanova et al. (2013) provided five new country examples, namely, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kyrgyzstan, Thailand and the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, which had achieved substantial improvements in health or access to services or implemented innovative health approaches (see Table 1.2 for selected indicators for these countries).

These are by no means isolated historical accidents. In Europe, life expectancy and health outcomes improved rapidly without any sustained upward push in per capita income (see Easterlin, 1996 and Easterlin and Angelescu, 2012). One of the lessons to be learned from these case studies and the European experience is that similar strides can be taken by countries in the developing world by adopting the policies and practices suggested by the “best practice” experiences of China, Costa Rica, Sri Lanka and Cuba. Furthermore, there are a variety of powerful low-cost options available that can improve health and raise life expectancy, which make for a quality life with less pain and suffering. We will delve into greater details of such country experiences and the lessons that can be learnt in subsequent chapters.

It should also be noted that there are a number of measurable economic benefits of better health outcomes. The first of these is the impact on the growth of per capita income. The direct benefits of better health are evident in higher productivity of healthy versus unhealthy workers. Also, healthy workers contribute to tax revenues and help expand desirable government programs including healthcare. So there is a powerful virtuous cycle of better health and higher incomes at work. Conversely, those who are ill are not so productive and make fewer contributions to the public purse. Rather they draw down revenue by requiring more health benefits.

Table 1.2 Selected indicators for China, Cuba, Sri Lanka, Costa Rica, Kerala (India), Tamil Nadu (India), Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kyrgyzstan and Thailand

Sources: World Bank (2013), WHO (2013), UNDP (2013) and Government of India (2013).

There are also subtle benefits of better health, particularly on infant mortality and the impact on demography. As birth rates adjust to increased survival rate that goes with increased life expectancy and lower infant mortality, a rapid demographic transition occurs from high birth and death rates to much lower birth and death rates. In this transition, the death rate falls more rapidly than the birth rate, resulting in rapid population growth and shifts in the age distribution of populations. There are more entrants into the labor force as the population surges and before family size adjusts to a larger and slowly aging population. The baby boom that occurs during this demographic transition to low population growth and a lower death rate (longer life expectancy) creates a hump in the age distribution. There are now more workers relative to the young and the elderly. This results in a temporary boost in aggregate supply and demand and perhaps more rapid growth as aggregate spending increases relative saving. As life expectancy increases and people can rely more on living longer, opportunities to plan for retirement arise along with saving for children’s education. These new savings help to fund investment opportunities that arise as incomes grow further.

There are quantitative estimates of how an increase in life expectancy makes its way through these various channels to impact living standards. Bloom, Canning and Sevilla (2004) estimate that one year of extra life expectancy raises GDP per person by 4% in the long run, while Jamison, Lau and Wang (2005) estimate that reductions in adult mortality explain 10–15% of global economic growth that occurred between 1960 and 1990. Furthermore, there is some evidence that better health matters more for poor countries compared with richer countries (see Bhargava et al., 2001). Putting all of these evidences together suggests that health and income growth are positively related over time, with some lags in adjustment and the possibility that causation runs in both directions.

Consider also the impact of poor health and the ebb and flow of epidemics on well-being and economic activity. From an analysis of historical trends, it is clear that epidemics resulted in economic, social and psychological devastation. The bubonic plague wiped out an estimated 30–60% of the population in Europe in the 14th century and over 25% of the world’s population. An estimated 100 million or more lives were lost as global population fell from an estimated 350–250 million. Because the plague killed such a large proportion of the working population, some economic historians believe that the rise in wages that resulted from a shortage of healthy workers was a stimulus to economic development. However, the agriculture sector had difficulties as cultivation and harvesting became difficult. The economies of the world took many generations to regain the standard of living an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- List of Acronyms

- 1. Introduction

- 2. HIV/AIDS

- 3. Tuberculosis

- 4. Malaria

- 5. Diarrhea and Other Water-Borne Diseases

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index