![]()

Part I

From Prosperity to Panic

Chapter 1

Illusion of Prosperity

I have always had considerable respect for those who pursue their entrepreneurial vision, risking their money and foregoing consumption during the first few years of their business with the hope of future gains. This is what I used to think of as the fundamental element of capitalism.

I had several role models who contributed to this respect. One of them, Petur Snaeland, the grandfather of one of my best childhood friends, began with a small auto garage in the 1940s. Through careful management and kindness to his employees, many of whom were former convicts, he managed to support his family of six. But things didn’t always go as planned for Snaeland. One day, his garage burned to the ground, leaving the family with no assets and no livelihood. In an attempt to comfort his wife, Snaeland gave her a big hug and said: “Don’t worry honey, nobody lost anything on this, except for us.”

With little but his name and mechanical skills, Snaeland got started again, this time with an equipment rental business he built up by restoring obsolete machinery he bought as scrap from the US military base in Keflavik, Iceland. Business was good in the postwar years and in 1952 he opened one of the first rubber factories in Scandinavia. As the years went by, his business grew and in 1968 he added a foam production factory. By the 1980s, his company was among the best-known brands in Iceland, bearing his name “Petur Snaeland hf.”

When capital controls were lifted in Iceland in the 1980s, competition in the furniture production industry got tougher, and in 1988, Snaeland, having overextended himself with an additional investment in a new production plant, was forced to file for bankruptcy. By the time he was ready to retire, he had not only lost his business and his pension, but also his wonderful family home, inherited by his wife from her father, the former mayor of Reykjavik.

In my view, Petur Snaeland was one of those capitalists who form the pillars of a great society—who keep the wheels of the economy turning. They get ideas, invest their savings, work hard, and either reap the rewards, or fail. And this is how it has been for centuries.

I used to think that all entrepreneurs were like Petur Snaeland. It was a naïve view that changed over time, but never did I imagine how far we could stray from these fundamental aspects of capitalism. In 2009, however, I came to see just how far, when serving as senior researcher for Iceland’s Special Investigation Commission. The Commission was set up to investigate the causes and events leading to the fall of the three largest banks in Iceland in October 2008. It issued its 2.400-page report on April 12, 2010.

One of the main discoveries of the investigation was a complex ownership structure: a cobweb of holding companies. This complex structure (see front cover image) was used to avoid consolidated accounting, to accumulate dividend payments through off-shore special purpose vehicles (SPVs), and to successfully tunnel money out of the banking system through easy access to risky borrowing. Under such structures, there is no limit to how much risk owners are willing to take. They have little or no skin in the game. In the case of the fallen systemically important Icelandic banks, creditors and the rest of society bore most of the risk. In a remarkably short period of time after privatization, the Icelandic banking system collapsed, with severe consequences for the Icelandic nation. Most of those responsible for the collapse, however, escaped serious financial and legal repercussions and, unlike Petur Snaeland, can comfortably say to their significant other: “Don’t worry honey, everybody lost, except for us.”

Iceland—the Yardstick of Luxury

“Wow, have you seen the bathrooms in this place? They are so nice they could be in Iceland,” my friend Tinna said as she came walking out of the restroom at the Zaytinya restaurant in downtown Washington, DC in January 2006. She and her husband were visiting DC for the first time, and in an attempt to be a good host, I had put together a small itinerary, a list of the must-sees in Washington, DC. I wanted to impress them with everything the US capital had to offer, but I never considered putting the restroom at Zaytinya on the list.

Tinna’s comment, however, underscored the state of affairs in my home country of Iceland, which had been experiencing outstanding economic growth for several years and had been recognized in my research at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as having too rapid a growth of credit. Tinna wasn’t one to be caught by the latest fad, or to be swept by a wave of lavish spending; so if the bathrooms of Zaytinya were catching her attention, something in Iceland truly must have changed.

A few months later, my husband and I moved back to Iceland, to our 80-year-old, 750-square-foot apartment in downtown Reykjavik, and since the original kitchen cabinets were about to fall apart, we decided to install new ones we found at a good price at IKEA. Unfortunately, every trip to IKEA took at least a couple of hours, no matter what the purpose. It wasn’t that IKEA was far away, but rather that everybody else was renovating as well.

The transformation of Iceland was obvious, and the crowds were not limited to IKEA. Designer furniture stores were busy too, and so were car dealers, and carpenters building summer cottages, and travel agents, and fashion boutiques, and the list goes on.

By December 2006, after seven months in Iceland, I wrote to my former colleagues at the IMF trying to describe life in Iceland:

The credit boom was evident all around Reykjavik, from banks to building cranes to the BMW dealership. It was as if Iceland had discovered a new oil field. Unfortunately, it had only discovered access to, and appetite for, easy credit. Iceland was indeed headed for a world-record credit boom.

Credit Boom

A credit boom is defined as rapid expansion of credit to the private sector, accompanied by rising asset prices. The boom is often followed by a bust, consisting of risk aversion on the part of the financial sector as asset prices fall again to sustainable levels, marked by unwillingness to lend under this price level uncertainty. This in turn causes a reduction in investment and consumption, and often results in a recession.

It is difficult to estimate a normal level of credit growth, especially in the case of underdeveloped countries that are on the path of structural changes to spur economic growth. One rule of thumb, derived from empirical work, points to a possible danger at a 17 percent real growth of credit, since that is the average annual real growth of credit during episodes that are associated with excessive cyclical movements in credit that have not been sustainable and have eventually collapsed.1 Any given country could thus be considered to be going through a credit boom if bank credit to the private sector rises by around 50 percent in a three-year period. This is not hard to grasp—since our economies, when healthy, grow no more than 4–6 percent in real terms over one year. If our banks extend credit to the private sector at a rate twice or three times that of the growth of the economy, chances are that safe investment opportunities, which yield high rates of return to cover the cost of credit and leave something on the table for the investors, become harder and harder to find. As Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas and his coauthors put it:

During a credit boom, financial markets participants have a distorted notion of risk. While it is difficult for bankers to assess the correlation of losses across borrowers and lenders over time, risk also tends to be underestimated during booms and overestimated in recessions.4 Moreover, assessment of the viability of investments by the market is distorted by implicit or explicit guarantees made by the government sector. Entrepreneurs and lenders price new projects under the best possible scenario, taking into account a government bailout in the worst-case scenario, and begin reaching for the bottom of the barrel to continue supporting the good times.5

To prevent the possible bad consequences of rapid credit growth, it is important for policy makers to identify the origin of the episode. While it is important to avoid “crying wolf” when credit growth may be the result of a simple catching-up process, it would be too optimistic to assume that rapid credit growth is simply the result of the system reaching a new and much higher “equilibrium level” of credit without any risks or need for action. In fact, such behavior on the part of policy makers can only be categorized as regulatory gambling, considering the devastating consequences faced by all citizens in the worst-case scenario.

When it comes to the possible causes of credit growth, the same medicine cannot be applied to all maladies. Financial stability instruments such as reserve requirements, dynamic provisioning, elevated equity ratio requirements, and tightening collateral requirements are among those measures that can be found in the policy toolbox to contain credit growth, in addition to a host of other prudential policy instruments, thoroughly documented in an IMF working paper by Hilbers and his coauthors, including myself, from 2005.6

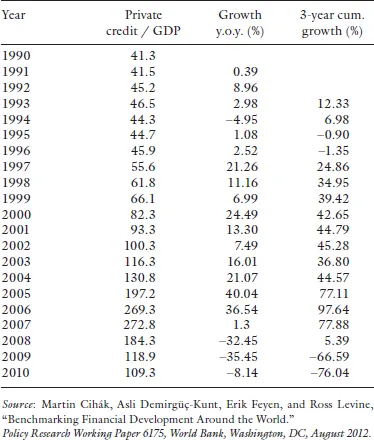

Considering the credit growth numbers from Iceland (see Table 1.1), it should have been easy to build a case for a public policy response. The numbers warrant a pause to think about the difference between what science knows and what government does in its duties to protect the interests of its citizens. According to the early warning signs and the rules of thumb described above, there was ample evidence to push for a policy response against the buildup of credit in the Icelandic system, at least from 2003, if not already in 2000. To be completely fair, it does take time to assemble statistics such as these, but that does not excuse the inaction on the part of the regulators, who had reasons to act over a five- to seven-year period before the system finally collapsed.

Table 1.1 Credit to the private sector by deposit money banks and other credit institutions as share of Iceland’s GDP 1990–2010

Credit Growth Research

My interest in the strategic behaviors of financial institutions began when I was working as a broker at the newly formed Icelandic Investment Bank (FBA) in 1999. A year earlier, I had been working as an analyst at the financially conservative Nordic Investment Bank (NIB) in Helsi...