This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ottoman High Politics and the Ulema Household

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In the 17th century, the elite household (kap?) became the focal point of Ottoman elite politics and socialization. It was a cultural melting pot, bringing together individuals of varied backgrounds through empire-wide patronage networks. This book investigates the layers of kap? power, through the example of?eyhülislam Feyzullah Efendielite.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ottoman High Politics and the Ulema Household by Michael Nizri in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Life of Feyzullah Efendi: A Typical Rocky Career Path of an Alim

Throughout his life Feyzullah Efendi experienced a series of upheavals. His biography exemplifies and explains the basic concepts of the legal-academic establishment of his time, something that is vital for understanding the period and cultural milieu in which he acted. Above all, his personal history is bound up with the processes undergone by the ulema in the 17th and 18th centuries.1 This book will show that Feyzullah followed a rather typical rocky career of progress and delay, together with a major fall from favor. Typically, too, a congruence of events made it possible for him to return to the centers of power.

Erzurum and the Sufi connection

Feyzullah was born in 1638 in Erzurum, the capital of the province of Erzurum in north-eastern Anatolia. His family originally came from the area of Karabağ (modern Azerbaijan), where for generations it headed the Halveti Sufi religious order. Religious orders were generally named after their founders, who developed mystical ways of bringing people closer to God. Thus every order (tarika) developed its own particular mystic rituals. The centers of Sufi activity (sing. tekke, zaviye) held ceremonies where the name of God was repeated many times to a specific rhythmic beat (zikr).

The distinguishing characteristic of the Halveti order was the custom of isolating oneself for a period of perhaps three or four days (halvet) at a time in order to cut oneself off from the travails of this world and to draw spiritually closer to God. At the practical level the emphasis was placed on fasting, silence, all-night prayer, meditation, and the repetition of the many names of God. It is worth mentioning at this point that during the 17th century the mystical Sufi movement became widespread and popular, with many adherents both among the elite and among the common people. The Sufi movement connected various sectors of Ottoman society, provided an identity and feeling of belonging, strengthened social cohesion, and nurtured folk religion (involving, for example, rituals around saints’ graves). At this time, the Halveti order was considered to be one of the largest and most popular Sufi orders within the Ottoman Empire.2

Feyzullah’s family was forced to leave Karabağ after the Shi’ite Safavids conquered the area and wrested control from the Sunni Ottomans at the beginning of the 17th century. Many of his family and many members of the Halveti order were killed in the course of the fighting. Consequently, the head of the extended family and the then head of the order, Sheikh Mustafa Efendi, Feyzullah’s uncle, moved to the city of Erzurum. At that time, Feyzullah’s father, Sheikh Mehmed Efendi, and the younger of the two brothers, was a boy of seven. The family’s move to Erzurum gave the city a tremendous boost. Sheikh Mustafa Efendi, together with his followers, did much to improve the city and to cause it to flourish.3

Once the family was established in Erzurum, Feyzullah’s father and uncle travelled to Istanbul, where they were granted an audience with Sultan Murad IV (1623–40), a great honor. They succeeded in acquiring a great number of appointments for themselves and their hangers-on, and even received a grant of agricultural land (ciflik) in the nearby city of Erzincan. This can be seen as the sultan’s way of demonstrating his appreciation of the family’s contribution to the development of Erzurum.4

Sheikh Mustafa Efendi remained the head of the Halveti order until his death in 1667. Feyzullah’s father then inherited the position and followed in his footsteps in everything connected to the development of the city. He established several mosques and a medrese (institution for advanced religious studies) in Erzurum and also stood behind the construction of a large bridge. Later, he was even appointed müfti of Erzurum.5 As a rule, müftis – apart from the Şeyhülislam himself – who issued religious rulings on issues of law and morality (sing. fetva) on the basis of religious law were not numbered among the senior level of the legal-academic establishment since they had not fully completed their religious training. Each of the main cities of the empire had an official müfti appointed by the Şeyhülislam (Grand Mufti)6 who himself served as the supreme religious authority. Apparently, the extended family received a sort of monopoly on the positions of kadı (judge) and müfti of Erzurum, and ruled for many years.7 The position of local judge was regarded as more important than that of the müfti since his authority was not only legal but administrative. For example, he supervised the operation of government officials, recorded financial deals, participated in the setting of tax rates and collecting taxes, and was responsible for repairing damage to the infrastructure.8 Even in times of crisis family members would continue to hold these positions, underpinning their status as one of the leading and strongest families in Erzurum.

Feyzullah’s distinguished ancestry on the side of both his father and mother (Şerife Hanım) contributed to his right to bear the title of seyyid. Even though

Feyzullah was recognized as a “true” seyyid, his family genealogy was probably a forgery. The title seyyid, like the title şerif (pl. eşraf), testifies that those who hold it descended directly from the Prophet. Such recognition brought its bearers great honor and certain privileges and many tried to claim the title fraudulently. Descendants of the Prophet were permitted to wear green turbans, were exempt from paying certain taxes, and could only be tried before another seyyid. In cities where there was a large community of descendants of the Prophet, the members chose a leader (Nakibüleşraf) to represent them. The senior personage was the head of the community of the Prophet’s descendants in Istanbul, and had considerable political clout.9

Manner of training

Feyzullah’s broad education was acquired privately through his father and relatives, and is described in considerable detail in his autobiography. At first, says Feyzullah, he received lessons from his father and a relative named Molla Seyyid Abdülmümin, who taught him the Quran, Arabic and Persian, literature and poetry, and Islamic law. Later, he learned syntax, grammar, semantics, rhetoric, and flowery phraseology from his cousin Molla İsmail Murtazazade, who was one of the best-known scholars in the area. Another relative who played a part in Feyzullah’s training was Sheikh Mehmed Vani Efendi, who instructed him in logic, geometry, Koranic exegetics, hadith (the sayings and traditions of the Prophet), astronomy, and numerous legal and theological works. This talented scholar, a native of Hoşab in the province of Van (eastern Anatolia), arrived in Erzurum after finishing his religious training, hoping for work as a teacher. Feyzullah’s uncle, Sheikh Mustafa Efendi, was impressed by him and his level of knowledge and took him under his wing. He even married off his daughter to him. That opened the way for Vani Efendi to engage in teaching and public preaching.

In addition to the varied areas of knowledge acquired by Feyzullah, his father also taught him the secrets of the Halveti order in line with the family tradition.10 Feyzullah makes no mention of formal schooling in one of the medreses in or out of Erzurum, and nor do any of those who wrote about him. This is surprising considering that since the middle of the 10th-century medreses have been the accepted institution of higher education in the Muslim world. However, as early as the pre-Ottoman period a variety of educational frameworks had been established. First of all, primary schools for basic instruction in Islam (sing. mekteb) were scattered throughout the Ottoman Empire. They provided children with a basic level of education but had no formal curricula. That education consisted principally of learning Quranic passages by heart, understanding the elementary principles of religion, acquiring basic literacy, and learning arithmetic. Most students did not go beyond that, unless they intended to go into government service.11 Traditionally, the mosque had served as an important learning center in which it was possible to learn religious studies. Even in the Ottoman period mosques continued to guard their didactic role, even attracting students from the medrese because of their high level of instruction.12 Instruction in the Sufi order included not only the principles of the order but also centered on instruction in areas which were considered less “popular” in the medrese, such as poetry, Persian literature, music, and so on.13

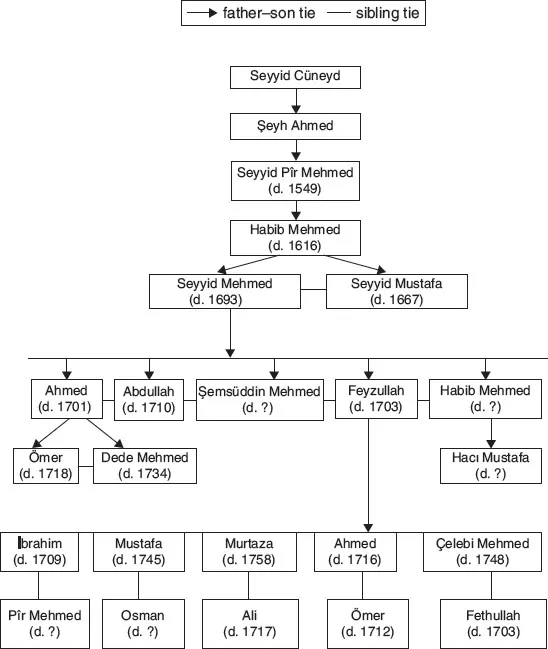

Figure 1.1 Feyzullah’s family tree

Source: Based on Feyzullah’s autobiographies. See Derin, Feyzullah, pp. 97–103; Derin and Türek, Hal Tercümesi, II, pp. 69–92.

Those destined to serve in the sultan’s household received their education in the palace school. At the same time, the training given in the homes of senior administrators was along similar lines to that offered in the palace school.14 In this context one must also mention the system of bureaucratic apprenticeship that provided broad training to future officials.15 Another common way of acquiring higher education in elite circles, as in the case of Feyzullah, was private tutoring with scholarly members of the family or the ulema.16 Moreover, in certain cases, higher education was obtained in several of the frameworks in tandem in order to broaden horizons as much as possible.17

Depending on the level of the medrese, a wide variety of subjects were studied. At the higher levels – the traditions of the Prophet (hadith), Quranic exegesis, and Islamic law – were st...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- A Note on Transliteration

- Introduction

- 1 The Life of Feyzullah Efendi: A Typical Rocky Career Path of an Alim

- 2 The Formation and Consolidation of the Kapı (grandee household)

- 3 The Rise of the Household to Hegemonic Status

- 4 Household Property, Sources of Income, and Economic Activity

- 5 The Contribution of Waqfs to the Preservation of the Power and Wealth of Households

- Epilogue

- Glossary

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index