eBook - ePub

Institutional Barriers in the Transition to Market

Examining Performance and Divergence in Transition Economies

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Institutional Barriers in the Transition to Market

Examining Performance and Divergence in Transition Economies

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Examines the institutional developments in 28 transition economies over the past two decades and concludes that, contrary to popular belief, institutions were not neglected; while personalities mattered as much as policies for outcomes, getting the basic institutions right was the most important aspect of a successful transition.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Institutional Barriers in the Transition to Market by C. Hartwell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Why are Polish meat stores four miles apart? So the queues don’t get tangled up.

Retold in Davies (2010: 22)

Jokes such as the one above were common throughout the Soviet Union and its associated satellite states during the years under communism, with only the location changing. More importantly, the jokes told under the communist regimes were not far at all from the truth. In each country under the yoke of communism, the continuation of an economic system that could not provide for its citizens resulted in rationing, lines for food and general economic stagnation. This reality was perhaps most evident in the Soviet Union, which, after 73 years under the communist system, still had (based on a “one-day check of [Moscow’s] meat stores by Government inspectors”) on one day in 1990 “no meat ... at 730 stores, or 57 percent” (Clines 1990). Lest we think that this day was an aberration, “in June [1990], 35 stores had no meat. In July, it was 65 stores, and in August, 272 stores, or 21 percent” (Ibid.).

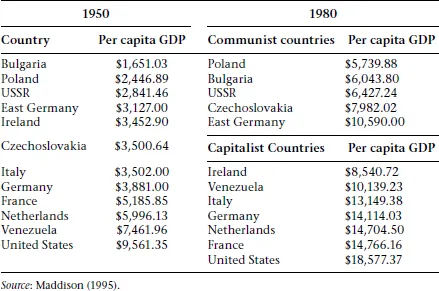

The ubiquity of the horrible economic (not to mention political) conditions was reflected in the continued and comprehensive subpar economic performance of communist states: in 1950, Czechoslovakia was fairly well developed (having avoided most of the devastation of World War Two), with a per capita GDP even above that of Ireland and on a par with Italy (by contrast, the USSR, which had been living under communism for 33 years at that point, had a measured per capita GDP of $2,446.89, behind that of Gabon at $3,108.00 and on a par with the new state of Israel at $2,817.00; Maddison 1995). By 1980, however, the USSR, Poland, and Czechoslovakia had standards of living far behind those of neighbors and Western countries (see Table 1.1). While Czechoslovakia had outpaced Italy in 1950, by 1980 Italy had nearly double the per capita GDP of the Central European nation, and the United States maintained its lead of output of nearly three times the size of the USSR. Perhaps nowhere was the difference between communism and capitalism more striking than across the two Germanies, where West Germany (the Bundesrepublik Deutschland or BRD) had a per capita GDP $4,000 greater than its eastern neighbor, the Deutsche Demokratische Republik or DDR (at least on paper, as the real gulf was most likely much wider); even adding West Germany’s per capita GDP in 1950 to the DDR in 1980 would not have equaled the Bundesrepublik’s per capita GDP in 1980.

This similarity across the communist countries was also to change drastically in two decades’ time as communism’s enforced egalitarianism crumbled and countries of the former Soviet bloc took varying steps toward building the market economy. In 1990, in the midst of economic transition and systemic crisis, Poland and Czechoslovakia had already begun to diverge in their per capita GDPs, as Poland’s GDP had fallen to $5,113 and Czechoslovakia showing a slight uptick from 1980 at $8,513 (the USSR, which was still mostly centralized and had not yet begun the transition, held firm with an official GDP per capita of $6,894).

Table 1.1 Per capita GDP (in 1990 International Geary-Khamis dollars) over time, 1950 vs. 1980

After a decade of transition, however, by 2000, the three countries’ GDPs were markedly different: in the first instance, the USSR had disappeared, replaced by the Russian Federation and 14 successor states, while the created entity of Czechoslovakia had undergone a “velvet revolution” which separated the country into two, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Beyond this geopolitical change, growth rates of the successor countries, and among all formerly communist countries, had begun to diverge rapidly, as the free-market reforms in Poland produced growth on average of 4.69 percent from 1992 to 2000, while the Czech Republic saw average growth of just over 2 percent following its split from Slovakia. The once and again Russian Federation, plagued by currency crises and war in Chechnya, saw a mighty fall from its official USSR statistics, contracting on average 2 percent per year from 1993 to 2000. The disparity in economic outcomes has become even more marked 20 years on from the beginning of transition from communism to capitalism; in 2009, according to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), output in Russia was still 99 percent of what it had been in 1989, while in the Czech Republic it was 135 percent and in Poland 181 percent of where it had been at the start of transition.

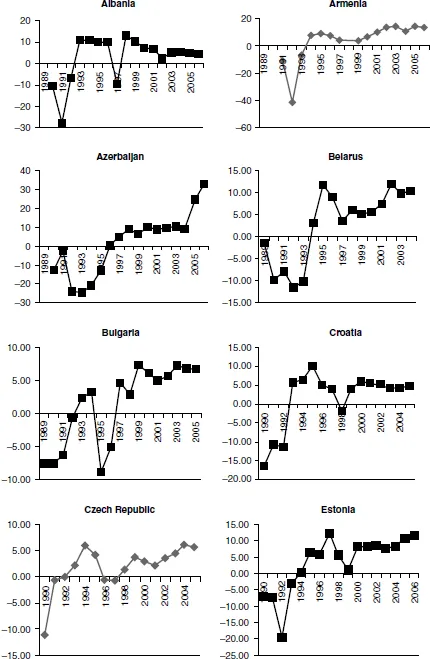

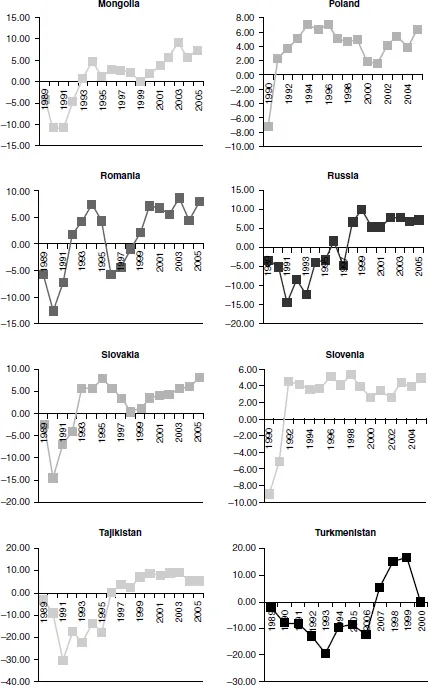

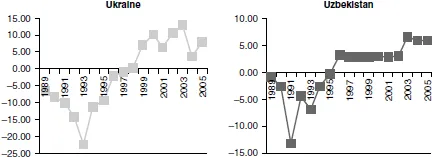

While these three countries are just a snapshot of the change across transition economies, economics performance across nearly all transition economies has been markedly different over the past two decades since Poland began its reform program (Figure 1.1 shows the differing performance of GDP for 24 transition countries from 1989 to 2006). How did these countries, that apparently were under the same system and fairly similarly aligned in their economics, diverge so substantially?

The challenge: economics literature and the explanation of transition

The difference in performance between capitalist and communist economies has been studied in economics for nearly a century, with landmark works such as Hayek (1948, 1973) and Kornai (1986) thoroughly detailing why communism failed as an economic system. However, the attempted transition from communism to capitalism presented the economics profession with a new set of challenges: what were the best ways to successfully effect such a transition? What exactly did transition entail? And most importantly, as presented above, why did different countries have such different economic outcomes in undertaking transition? What factors and variables were responsible?

Figure 1.1 GDP percentage change by country, 1989–2006

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators 2009.

In one important sense, the search for the explanation of the divergence of economic growth patterns of transition economies is merely part of the largest and most enduring question in economics: why do some countries grow while others don’t? Why are growth paths erratic over time? As in other literature tracing the difference in the wealth of nations, the question of just why there has been a difference in the economic performance of transition economies has been explained as a function of two major factors:

•Initial conditions: early work from de Melo et al. (1996) posited that at least the early stages of transition were influenced by the country’s initial conditions, including the extent of industrialization, the amount of time spent under communism, the extent of integration into COMECON (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance) trading blocs, the extent of natural resource endowments, and the distance of the country from Western Europe. While acknowledging that initial conditions were not necessarily a determinant of future success, they did go quite some way to explaining the severity of what Kornai (1994) called (and Popov 2007 examined intensely) the “transformational recession,” which made intuitive sense: the farther away from your starting point you had to travel, the longer and more painful it was going to be.

•Policies: Shifting from initial conditions, researchers took up the issue of speed and sequencing of reform policies (encapsulated in the catchy but incredibly imprecise debate of “shock therapy” versus “gradualism”) as possible determinants for the recovery of countries and the increasingly divergent outcomes occurring under transition.

Other minor determinants of transition outcomes (depending upon the specification) have also been identified in the literature, including the role of the specific political and civil society leaders and their personalities in influencing policies. Although this aspect has been somewhat neglected as a focus of research in transition economics (due to the fact that personalities influence policies), personality has been noted by Balcerowicz (1995) as a possible determinant of economic outcomes. In particular, the personalities of the people in power (and whether they had been in power under communism) and the personalities that were part of political change played a large and diverse role in determining the speed of transition and political support behind transition, and, thus, outcomes.

Underpinning all of these factors, and indeed the goal of the transition itself, was the role of institutions, and how different economies created or saw the creation of institutions that were better suited to facilitate the market economy. Institutions began to emerge as a factor in transition economics with North’s (1997) application of his earlier work on “new institutional economics” (NIE) to transition, and in his wake many economists who had just focused on output patterns turned around and claimed that institutions in transition economies were neglected. This refrain soon became the conventional wisdom, with a plethora of studies (for example, Kołodko 1999, Ahrens and Meurers 2001, Djankov et al. 2002a, Murrell 2006) pointing to the need for institutional change as the precursor to a successful transition.

However, little work has been done on actually examining the validity of the claim that institutions were neglected in transition economies. This has been due to several reasons, with the major one being that there is little agreement in the work linking transition outcomes with institutions on the precise definition of what an “institution” actually is: various papers have contended that “newspapers, supermarkets, and even phone booths [are] institutions” (Voigt 2009a: 2). While some papers tried to narrow down institutions into categories such as formal and informal or chose to focus on governmental agencies and political structures (Murrell 2006), even systematic work on institutions in transition lacked a common definition of what was and what wasn’t an institution (see, for example, Beck and Laeven 2005).

Beyond this basic methodological point, the work that has been done empirically on the influence of institutions in transition has neglected to answer a basic question: if institutions were indeed neglected, what impact did this have on growth and other economic outcomes? The blanket assertion that transition economies neglected building appropriate institutions should thus show up in the data, with countries that failed to build the appropriate political/economic structures suffering as a result (of course, determining such a result is difficult if you don’t first define what an institution is). This empirical link between neglected institutions and deleterious economic outcomes has not thus far been made.

The corollary to this gap in our knowledge of institutions in transition is the more salient point, from a policy point of view: which institutions are most important for growth and the successful completion of transition? Put differently, what could have been done differently in Belarus to make it more like Estonia (and what could have been done differently in Estonia to make it closer to Poland)? Which institutions could have been focused on by policymakers, and which institutions were crucial to increase the welfare of a country’s citizenry?

The purpose of this book is to explicitly fill this hole in the transition economics literature, and to, in the words of Balcerowicz (2008), “identify more precisely those states of institutional variables which are barriers to growth and ... derive, from this diagnosis, the guidelines for successful reforms.” In this sense, this book follows from both the NIE work of North (1981, 1992), Knack and Keefer (1995), Acemoglu and Johnson (2005), and Acemoglu et al. (2005), and the transition work of Moers (1999), Havrylyshyn and Van Rooden (2003), Beck and Laeven (2005), and Havrylyshyn (2006a), but seeks to make an explicit link between the strands of new institutional economics and transition economics along the lines of Balcerowicz (1995, 2008). It also applies the NIE tenets espoused by Joskow (2008: 5) in that

Institutions may be analyzed using the same types of rigorous theoretical and empirical methods which have been developed in the neoclassical tradition whilst recognizing that additional tools may be useful to better understand the development and role of institutions in affecting economic performance.

Using this approach and the literature in both NIE and transition economics, this book will attempt to rigorously examine empirically the question of which institutions contributed to transition (and which were less important). Using as a starting point the problems in the existing literature noted above, this will be accomplished through five separate points of research:

1.Define what an institution actually is, in terms of its relevance for economics and applicability to the transition process, and how they may change

As noted above, the lack of precision on what an “institution” is has led to different analyses and different results on their influence in transition. Clarifying the boundaries between institutions and policies (while recognizing that the lines are not as clear as we would hope) is the first step in teasing out the relationship between institutions and transition, and so our first action will be to define an institution. This exercise will build on a long and rich history of economic literature, beginning (for our purposes) with Smith (1776) and continuing through the so-called old and “new institutional economics” debate that continues today. Via this examination, I will place the transition literature into the broader growth and institutional literature (as noted ab...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Defining and Measuring Institutions

- 3 Two Decades of Transition and Institutional Research: A Review

- 4 Institutions in Transition: Were They Really Neglected?

- 5 The Relative Importance of Institutions in Economic Outcomes in Transition

- 6 The Relative Importance of Different Institutions in Transition

- 7 Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

- Data Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index