- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This edited volume explores development in the so-called 'fragile', 'failed' and 'pariah' states. It examines the literature on both fragile states and their development, and offers eleven case studies on countries ranking in the 'very high alert' and 'very high warning' categories in the Fund for Peace Failed States Index.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Theory and Themes, Complexity and Challenges

1

Beyond the Usual Suspects: Complexity of Fragility and Analytical Framework

Anthony Ware

Making development work in fragile states is one of the biggest challenges for [the] international community . . . Fragile states are the hardest countries in the world to help develop. Working with them is difficult and costly and carries significant risks. Aid programmes in fragile states pose difficult policy dilemmas. All too often, donors have made the calculation that it is less harmful to do nothing or to rely on humanitarian responses.

(DFID 2005, pp. 3, 5)

‘Fragile states’ matter

How to engage with so-called ‘fragile states’ has emerged over the past few years as a key priority of the international development community, largely in response to increased emphasis on human security and peacebuilding in development, as well as state effectiveness (Mcloughlin 2012). There has also been a belief that fragile states are closely linked with transnational security threats, although many scholars challenge this correlation (e.g. Brock et al. 2012; Carment & Samy 2009; Patrick 2011). Nonetheless, as Chandy (2011) has noted, in the space of just a few years, fragile states have moved from the periphery of the international development agenda to become a key focus of global aid.

Most development indices demonstrate that aid has had only limited impact on poverty reduction in ‘fragile states’. Thus, until recently donors largely prioritised funding for states with relatively effective governments and stable macroeconomic policies. Good governance was believed to be an essential prerequisite for effective development. However, the reasons behind ineffectiveness of aid in fragile situations are increasingly being reassessed, and factors beyond governance are also being identified. The UK bilateral donor, the Department for International Development (DFID), for example, has suggested that ‘there are three reasons why aid has failed to reduce poverty in fragile states: there has not been enough aid; the aid provided has been delivered at the wrong time; and it has been delivered in ineffective ways’ (DFID 2005, p. 11). It is notable that governance was not listed at all as a cause of limited effectiveness, although it seems obvious it is still a factor.

There is growing recognition that difficult sociopolitical contexts do not, of themselves, preclude development effectiveness. Rather, it is being increasingly recognised that the issues being dealt with in these situations are highly complex and highly contextual, requiring significant time, funding and innovation to address, with uncertain outcomes. ‘Effective aid in fragile states depends on donors delivering aid differently . . . with new ways of working that better conform to fragile states’ characteristics and needs’ (Chandy 2011). This volume picks up that theme.

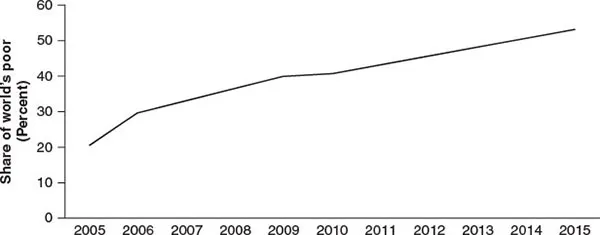

Facilitating poverty alleviation and development in so-called ‘fragile states’ matters. Depending on definitions, estimates for the number of people living in these vulnerable contexts range between one billion to one-and-a-half billion people (Collier 2007; IDPS 2011). In the early 2000s, fragile states contained only 14 per cent of the world’s population but nearly a third of the world’s poor people, and accounted for 41 per cent of all child deaths (DFID 2005). As progress is made in poverty reduction in more stable, less vulnerable contexts, the world’s absolute poor are becoming increasingly concentrated in ‘fragile states’. As Figure 1.1 clearly illustrates, assuming for the moment we are satisfied adopting the Failed States Index (Fund for Peace 2013) definition of fragility, almost half of the world’s poor now live in such states, and this percentage is rapidly rising. Because of this, the World Bank (2007) notes a 50 per cent higher prevalence of malnutrition, 20 per cent higher child mortality, and 18 per cent lower primary education completion rate in states classified as ‘fragile’, as compared with other low-income countries. Two-thirds of the world’s remaining low-income countries are ‘fragile states’ (Chandy 2011).

A link between poverty and fragility thus appears undeniable, and for that reason addressing fragility has now become almost inseparable from global commitments to fight poverty, achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and develop post-2015 frameworks.

One implication of this is a growing prioritisation by bilateral donors of the need to address fragility. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggests that, by 2007, 38.4 per cent of global ODA was going to ‘fragile states’ (OECD-DAC 2009), and the increase in funding is continuing. DFID reports an increase in official development assistance (ODA) to ‘fragile and conflict-affected states’ from 22 per cent in 2010 to 30 per cent by 2014–2015, and that by 2013 four of the top five aid recipients of UK ODA will be on DFID’s list of ‘fragile states’ (IDC 2011, 2012). Over three-quarters of Australia’s bilateral aid goes to ‘fragile states’, and, at least until its assimilation into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), AusAID considered its focus on fragility to be a defining feature of Australia’s aid programme (AusAID 2011; AusAID-ODE 2011). Seven of AusAID’s top ten aid recipients in 2013 were ‘fragile states’. Nonetheless, data show that ‘fragile states’ continue to fall behind developmentally (OECD-DAC 2009), and agencies acknowledge that aid delivery in such settings ‘is more costly and more complex’ (AusAID 2010, p. 1).

Figure 1.1 Share of the world’s poor living in fragile contexts

Source: Chandy & Gertz (2011).

While there continue to be advances in theory and practice, just a few years ago the OECD expressed concern that

International actors have not yet adequately incorporated into policies or practice a sufficiently nuanced understanding of the dynamics of fragility and its variations, or developed appropriately contextualised strategies.

(OECD 2008, p. 7)

A very diverse range of factors contribute to fragility, greatly complicating development in these difficult sociopolitical contexts. Violent conflict is the most common factor. In fact, conflict is so synonymous with fragility that most literature and development policy focus primarily on this factor; some 70 per cent of ‘fragile states’ have experienced violent conflict since 1989 (IDPS 2011, p. 1). However, a great diversity of other structural and economic, political and institutional, social, and international factors can also contribute, including: limited government capacity and will; corruption and neopatrimonialism; elite and ethnic factionalism; and low levels of legitimacy – as well as poverty, inequality, exclusion, demographic stress and factors largely outside the control of the state, such as historical legacy, international failures, vulnerability to external shock (for example, natural disaster or environmental problems) and difficult relations with neighbours or the international community (Mcloughlin 2012).

Responses to fragility are only further complicated by donor attitudes and the politics of aid. Despite the prioritisation of fragility by some donors, ‘fragile states’ remain ‘ “under-aided”, even against allocation models that take their performance into account. Aid flows [to fragile states] are excessively volatile, poorly coordinated, and often reactive rather than preventative’ (Mcloughlin 2012, p. 6). Selectivity is a key component in this equation: a majority of global ODA to ‘fragile states’ goes to just five such countries, with the vast majority of states considered ‘fragile’ receiving very little assistance (OECD-DAC 2009). Such decisions, to restrict aid flows to many fragile states, are heavily influenced by critics of the governance of these states, some of whom go so far as to make statements to the effect that ‘Aid is rarely an effective development tool in fragile states’ (Zürcher 2012, p. 461).

Central to the issue of development effectiveness in difficult sociopolitical contexts is the struggle to identify appropriate policy approaches. The diversity of factors contributing to fragility makes each situation unique, necessitating highly contextual and tailored responses. Thus, despite the numerous attempts to articulate generalised principles for development in situations of fragility (e.g. Kaplan 2008; OECD 2007, 2008; World Bank 2011), a strong chorus from commentators continues to highlight the fact that current approaches are problematic, or that we have more knowledge of what does not work well than of what is effective (e.g. Carment et al. 2011; Naudé et al. 2011; Nay 2013). This volume adds to this critique of current approaches, as well as contributing analysis which will hopefully lead towards more effective policy and engagement.

Given all this, it is hardly surprising that the ‘fragile states agenda’ is surrounded by a great deal of critical debate (Mcloughlin 2012). The term itself is highly contested, with some arguing, for example, that it is inherently ambiguous and analytically imprecise (e.g.Carment et al. 2010; Naudé et al. 2011; Putzel & Di John 2012), that it is pejorative and inherently political (e.g. Bilgin & Morton 2002), that it contains implicitly normative assumptions (e.g. Stepputat & Engberg-Pedersen 2008), or that the term constitutes a powerful Foucauldian discourse more about Western strategic and financial concerns than about the needs of the poor within these contexts (e.g. Chomsky 2006; Nay 2013). Stepputat & Engberg-Pedersen (2008), for example, argue that the debate on fragility suffers from three mistaken assumptions, namely that: (a) different fragile situations share sufficient characteristics to allow generalised policy responses (b) social change can be planned and engineered; and (c) that a Weberian conceptualisation of the state is a relevant goal in all contexts (Mcloughlin 2012).

This volume adds to the critical discussion of development in difficult sociopolitical contexts by exploring the factors contributing to fragility in 11 diverse case studies, and then exploring the actors, roles, approaches and modalities which offer the greatest evidence of effectiveness (or ineffectiveness). It also does so by going well beyond the ‘usual’ examples of ‘fragile state’ case studies most often studied and commented on, to consider examples drawn from a wide spectrum of vulnerability, contexts whose fragility is primarily located variously in political, economic, social and external factors. This volume also introduces studies from a diversity of disciplinary perspectives. This diversity adds considerable richness and depth to the discussion of development in contexts of fragility.

Origins and methodological approach

The origins of this volume lie in my own research into effective development in Myanmar prior to the current political transition. This research culminated in a roundtable symposium entitled ‘Development in Difficult Sociopolitical Contexts: Fragile, Failed and Pariah’, hosted by the Centre for Citizenship, Development and Human Rights, Deakin University, in September 2012. The link from my research to this symposium has been discussed at some length in the Preface, together with the questions and hypotheses which prompted the symposium.

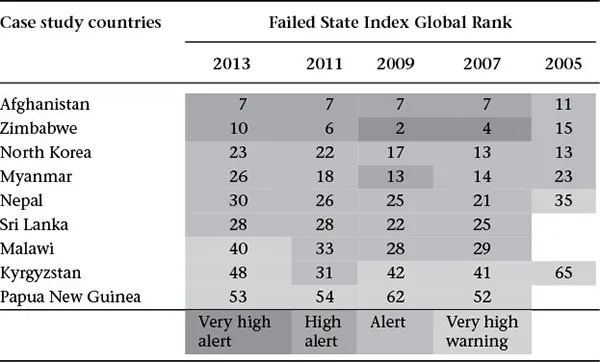

Clear criteria were adopted in the selection of case studies to contribute to this volume. Primarily, these focused on exploring a greater breadth of ‘fragile’ contexts than is often considered in much ‘fragile state’ literature, to deeply explore the impact of context, and on selecting many case studies that are still well short of the near collapse of state functionality implied by the term ‘failed’ state. Fundamentally, a diversity of studies were sought, covering a diversity of factors contributing to fragility, including political and institutional, structural and economic, social, and international or external factors. Studies were sought primarily from contexts within Australia’s strategic national interest areas, and from a broad cross-section of states across the top four alert bands on the Fund for Peace’s Failed States Index, namely, the ‘very high alert’ through ‘very high warning’ levels. The resulting contributions are shown in Table 1.1 against the Failed State Index rankings for five of the past nine years.

As can be seen, the resulting case study contributions cover a wide spectrum of contexts, including those commonly considered ‘failed states’, ‘fragile states’ and ‘pariah states’. The weight of the studies is towards those experiencing concerning levels of fragility, but in which widespread violent conflict and lawlessness are not dominant factors. It is believed that this diversity of contexts adds to the uniqueness and value of this study.

Contributions were also deliberately invited from a wide variety of disciplinary backgrounds, to expand the array of perspectives, with contributions included from development economics, anthropology, international relations and development studies. This book is thus largely qualitative, although not exclusively so. Some chapters are based on significant fieldwork, including interviews and participant observation. Others primarily analyse data and policy. Nonetheless, and despite contributors adopting their own disciplines’ descriptive narrative style, a constant analytical framework runs throughout the volume. Contributors were all asked to analyse two key issues: (a) the primary causes and character of the fragility in their context, explained via a historically informed description of the context focused primarily on state–society–international interrelationships; and (b) which different actors, approaches and/or modalities are more naturally able to facilitate effectiveness within the particular context. This framework is more fully developed and explained below.

Table 1.1 Global rank of case study countries on the Fund for Peace Failed State Index

Source: Author compilation from Fund for Peace Fragile State Index (selected years).

Given that the process which produced this volume involved preliminary briefings on this framework, considerable discussion between contributors and several rounds of peer and editorial review of contributions, the diversity of style and content contained in the chapters is both intriguing and instructive. Among other things, it shows the contributors repeatedly underscoring, in their own research and writing styles, the central importance of context and the difficulty of deriving generalised policy prescriptions across the diversity of causes of fragility. It also shows a strong desire by several contributors to rigorously critique labels and terminology, as well as generalised policy approaches. Nonetheless, this volume does contribute strongly to an analysis of actors, roles, approaches and modalities in addressing the various causes and characteristics of fragility – the ‘who does what’ of development in situations of fragility.

Definitions of key terms

Until this point in the chapter, I have frequently adopted the term ‘fragile state’ in this volume, but have done so somewhat reluctantly, using inverted commas to highlight the contested nature of the terminology. Despite the subtitle of the book using these terms, one of the contributions of this volume is a critique of the application of labels such as ‘failed’, ‘collapsed’, ‘fragile’, ‘weak’, ‘pariah’, ‘rogue’, ‘de facto’ and so on, to particular states. I, together with most of the contributors in this volume, am quite critical of much of the use of this terminology, not to mention the adoption of these labels into typologies. The empirical, normative, parochial and hegemonic shortcomings of such endeavours have already been noted, and will be highlighted again in Chapter 2 as well as in many of the case studies.

In response to such concerns, the development community is now increasingly favouring use of broader terminology, such as ‘fragility’ or ‘situations of fragility’, which at least captures the fact that the issues are not exclusively located in the nature and boundaries of the state, but may equally relate to non-state actors, regional contexts and international interrelationships (Mcloughlin 2012). Broader terms such as these have been encouraged throughout this volume. Nonetheless, there are a number of commonly used terms which require definition before proceeding.

‘Fragile states’

There is no internationally agreed definition for the term ‘fragile states’ or the preferred term ‘fragility’. The oldest definitions are derived from the World Bank’s now disused classification of Low-Income Countries Under Stress (LICUS), and the most widely used economic definitions are still based on the Bank’s replacement Country Policy and Institutional Assessments (CPIA) (Baliamoune-Lutz & McGillivray 2008). Both definitions rely on World Bank composite measures assessing vulnerability resulting from economic management, structural policies, social inclusion and equity policies, and public sector management. However, CPIA scores are not designed specifically for assessing fragility, and do not contain any measures of political stability, security or external factors (Cox & Hemon 2009).

Most development agencies define the terms ‘fragile’ or ‘fragility’ in terms of an inability or unwillingness of the state to perform functions necessary to meet the basic needs and expectations of the people. DFID (2005, p. 7), for example, defines ‘fragile states’ simply as ‘those where the government cannot or will not deliver core functions to the majority of its people, including the poor’, defining core functions as territorial control, safety and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Part I: Theory and Themes, Complexity and Challenges

- Part II: Case Studies: Development in So-Called ‘Fragile States’, ‘Failed States’ and ‘Pariah States’

- Part III: Conclusion

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Development in Difficult Sociopolitical Contexts by A. Ware in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.