This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Money and Trade Wars in Interwar Europe

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This books explains, on the basis of archival evidence and a simple economic model, why and how the gold standard collapsed in the interwar period. It also reveals how bilateralism and dirigisme in international financial relations emerged from the collapse of the universal gold standard, and how this poisoned international relations.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Money and Trade Wars in Interwar Europe by ALESSANDRO ROSELLI in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Financial Services. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Gold Standard Reinstated

1

War Reparations and Hyperinflation in Germany

1 Inter-Allied war debt and Germany

The First World War was characterized financially by a complicated web of loans between the Allied powers. At the end of the war (November 1918), total indebtedness amounted to around $21.6bn.1 The defeat of Germany was followed by huge reparations imposed on her by the victors. However, payment of reparations was closely linked to the settlement of the war debts, and the attitude of the Allied powers towards Germany was strongly influenced by their respective debit–credit positions. The United States had the biggest net credit position, followed by Britain. The American position was one of credit for $7.1bn, with a debit of just $0.4bn. The United Kingdom had lent $9.3bn to other Allies (mainly Russia, France and Italy), but also borrowed $6.1bn, mostly from the United States.

The rest of the Allies were net debtors: France lent $3.1bn, mostly to Russia, Belgium and the United States, but borrowed $4.2bn from Britain and the United States; Italy was in debt to the United Kingdom and United States for $3.2bn, having lent a total of $0.3bn; Russia was the biggest debtor, owing $4.9bn, mostly to Britain.2

The burden of lending fell on the United Kingdom in the first three years of war, before being passed to the United States. After the Armistice of 1918, inter-Allied lending continued, in particular on the part of the United States and Britain; France was also an active lender in both periods. Germany had been the banker of the Central Powers.3

Mainly because of the accrued interest, total debt among the former belligerents had accumulated by the end of 1923 to around $28.3bn, with the United States and Britain attaining net credit positions of $11.9bn and $4bn respectively. Loans were measured in terms of money, but actually consisted of indispensable commodities that a country could not obtain at home: A variety of goods including clothing, food, cotton nitrates, chemicals, steel, copper, engines, ships, and munitions.4

It is understandable that France was particularly anxious to get money from Germany, in view of the heavy losses suffered in terms of lives and physical assets, while the animosity of the United Kingdom was tempered by its different financial position. The United States, the most significant Allied creditor, did not even claim war reparations from Germany. In the early months of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, Hjalmar Schacht, who would become a prominent figure in both the Weimar Republic and the Nazi regime, still expected a generous peace, thinking that the real European problem was the huge pile of debt already accumulated by every belligerent country, and that what was badly needed was a reconstruction plan rather than an additional debt burden on Germany.5

‘Germany’s economy was exhausted but not in ruins’,6 after signing the Armistice without even having been invaded by the Allies: Many Germans felt that their country had been defeated not by the enemy’s army but by faltering morale at home. The Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919, produced deep disillusionment and, in Germany, it was often seen as an attempt by the Allied powers to gain an economic victory after failing to win the war on the battlefield.

Article 231 of the treaty – the ‘article of shame’– humiliatingly attributed to Germany sole responsibility for all war losses and damages. Article 232 stated that Germany would make compensation for those losses and damages, but did not specify the total German reparations bill. It also considered Germany’s specific violations of its treaty with Belgium as a separate case. In addition to all the above, Germany would reimburse Belgium the sums it borrowed from the Allies. Article 233 stated that the total amount of reparations would be fixed by a Reparation Commission which was to be established. Article 235 determined an ‘interim payment’ of the equivalent of 20bn gold marks, to be paid in 1919, 1920 and the first months of 1921.7 Out of this sum, the expenses of the armies of occupation and the cost of some supplies of food and raw materials would be met. The balance of the interim payment would be reckoned towards the amount due for reparations, according to Article 233.8

In the words of Moritz Bonn, an adviser to the German government who was firmly opposed to the Allies’ position, these 20bn gold marks ‘were merely a kind of hors d’oeuvre after which the real feast was to begin’.9 In fact, in the ‘interim period’ Germany paid in capital goods, and – according to this critic – these goods were valued far below the price they would have fetched on the German domestic market. According to the Reparation Commission, the value of these goods was esteemed at only 2.6bn gold marks, while the Germans valued them at several times more: ‘[A]bout 8bn gold marks’ – wrote Bonn – ‘although the loss to Germany far surpassed this sum’.10

At Spa in July 1920, the Allies allocated the proceeds from reparations among themselves, with the largest share going to France.11 After long and difficult discussions, the precise amount of total war reparations was determined on 27 April 1921 by the Reparation Commission, de jure an independent agency established by the Allied governments, at the value of 132bn gold marks, a figure based neither on specific Allied claims nor on any estimates of Germany’s debt sustainability. In fact, the commission received itemized initial ‘estimates’ of the damage suffered by all the Allies and by the ‘associate’ countries: 18 countries in total, with France, Britain, Italy and Belgium presenting the highest claims. But the commission dismissed these specific claims and officially stated that they were not used as a basis to calculate that final figure of 132bn gold marks. The commission pointed out that it was unclear whether the amounts, denominated in different currencies (for instance, Italy’s claims were in lire, France’s in francs, Britain’s in pounds), were at current or 1914 monetary values, and concluded that any conversion to German gold marks would be practically impossible. The commission refused, however, to make public both the items not accepted, and the haircuts of the accepted items.12

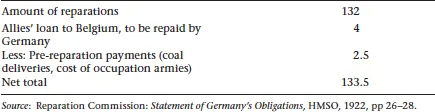

That sum of 132bn gold marks was more than double the German net national product (NNP) at gold parity for 1913 and, according to some estimates, would be more than three times the NNP for 1921 (we shall return to national output statistics later, while dealing with the sustainability of German war debt). The denomination of reparations in gold marks implicitly fixed the amount in dollars ($31.4bn), since the dollar price of gold had not been altered during and after the war.13 In addition, the Schedule of Payments which the commission submitted to the Germans included the Belgian debt owed to other Allies, which was equivalent to 4bn gold marks, although some items – whose total amount would be determined by the commission – were to be subtracted from the total sum of 132bn gold marks: The reparations already paid by Germany, as pre-reparation payments, compensation for German state properties in ceded territories,14 and the sums owed to Germany by other enemy powers.15 As Barry Eichengreen has pointed out, ‘no issue in twentieth-century economic and political history has been more hotly contested than the realism of this bill’.16

2 The London Schedule of Payments

The ‘London Schedule of Payments’, as it is known, was approved on 5 May 1921 by the Allied Supreme Council and, on the same day, presented to the Germans as an ultimatum: If it were not accepted, the Ruhr region was to be invaded (the Ruhr, rich in coal resources, would anyway become a very contentious issue, as we shall see below). The schedule also defined the instruments through which those payments were to be made. The sum of 132bn gold marks was divided into three categories of bonds, named A, B and C. The A bonds amounted to 12bn gold marks and required annual servicing payments of 6 per cent (5 per cent as interest and 1 per cent as a contribution to the bonds’ sinking fund): The B bonds carried the same interest and amounted to 38bn gold marks. The capital of 50bn gold marks (12bn + 38bn) was, in effect, the figure that would have burdened Germany, since the remaining 82bn gold marks (which were represented by the third category of bonds, the C bonds) would be credited, at no interest, to the same Reparation Commission and would be effectively issued sine die: That is, only after it had been established that Germany, by then on its way to recovery, really would be able to pay.17 Arguably, payment on this item was never seriously expected.18

In reference to the A and B bonds, there was no official earmarking for specific purposes, even if it was implied that each category would fulfil a certain function related to different kinds of debt.19

The schedule’s request was accepted on 10 May 1921, under pressure by the Weimar government of Joseph Wirth (whose delegation was led by Walther Rathenau, a cultured and highly respected man and a prominent industrialist).

A ‘reparations accounting’ was presented by the Reparation Commission in 1922.

Table 1.1 Statement of German obligations, 30 April 1922 (in billions of gold marks)

Unclear is the number of years it would take for the 50bn gold mark debt to be discharged. If any annual payment included 1 per cent for amortization (see above), this should have been 100 years; instead, a time span of 30 years was frequently cited. Certainly, no specific maturity was indicated in the Schedule of Payments. One cannot escape the impression that nobody really believed that this huge obligation – even for the lesser sum of 50bn gold marks – would ever be duly fulfilled.

There was a dilution of the German debt over time, which reduced the net value of the bonds as given above. C bonds, however, cannot be seen as mere window dressing to appease public opinion in Paris: Even if partly postponed, a total debt of 132bn gold marks was hanging over Germany and could not simply be met with indifference by public opinion in Germany.20 The Allies had hoped to place these bonds with investors, but were disappointed. Given the inability, or at least reluctance, of the debtor to pay, they were hardly considered a good investment.21

We need only consider the annual repayment on 50bn gold marks to confirm the shaky foundations of reparation accounts. At 6 per cent this would have come to 3bn gold marks; instead, German annual repayments were determined by the Reparation Commission using a different method, which set them at 2bn gold marks plus 26 per cent of the value of German exports (or an equivalent sum based on an index proposed by Germany that had to be accepted by the commission). The adoption of such a parameter was meant to make the debt more sustainable, by partially linking repayments to German economic strength: If and when a German economic recovery occurred, its payments would proportionally increase.

Given that German exports at the time were estimated at 5bn gold marks per year, of which 26 per cent would be 1.3bn, this would result in a total annual payment of 3.3bn gold marks which would exceed the 6 per cent value originally mentioned. The 1.3bn was mostly to be taken directly from the levy on exports, but also from maritime and land customs duties along with other sources proposed by the Germans and accepted by the commission. The Committee of Guarantees, established by the Allies, would secure the implementation of the schedule. The problem, of course, was how to find those 2bn gold marks that were to make up the bulk of the annual payments. The difficulty of reaching agreement on this highly contentious issue is demonstrated by a note from the Committee of Guarantees addressed to the German government on 28 June 1921, which estimated that each year Germany could pay 1.2bn gold marks in kind, 200 million gold marks from customs duties and 1.25bn from a levy on exports, thus leaving a payment deficit of 650 million gold marks.22

Following the presentation of the schedule, Germany paid, mostly in foreign currency, the equivalent of around 1.5bn gold marks between August and November 1921, and a final sum of around 150 million gold marks in the first half of 1922. These payments were not the result of any surplus in German foreign accounts, but were done mainly by Reichsbank’s purchases of gold and currency on the foreign exchange market (through the creation of additional paper marks), and by loans granted by Dutch and Italian banks.23 It should be noticed, in this regard, that in 1921 the paper mark was still attractive as a speculative currency. Numerous small-scale foreign deposits were made at German banks, in the (mistaken) expectation that the mark would finally recover, given the relative strength of the German economy (as we shall see later).24

No further substantial cash reparations payments ensued until after the Dawes Plan of 1924, although payments in kind continued (mainly coal,25 timber, chemical dyes, pharmaceutical drugs, livestock and machinery, but also state-owned property in territories transferred to the victors).26 As a result of the cash shortage, on 6 October 1921 the German minister of Reconstruction, Walther Rathenau, and the French minister of Liberated Zones, Louis Loucheur, signed an agreement by whic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I The Gold Standard |Reinstated

- Part II The Gold Standard Collapse: Nationalism and Bilateralism in International Financial Relations

- Part III What Europe?

- Postscript

- Notes

- References

- Archives

- Index