eBook - ePub

German Visions of India, 1871–1918

Commandeering the Holy Ganges during the Kaiserreich

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The wide-ranging fascination with India in Wilhelmine Germany emerged during a time of extraordinary cultural and political tensions. This study shows how religious (denominational and spiritual) dilemmas, political agendas, and shifting social consensus became inextricably entangled in the wider German encounter with India during the Kaiserreich.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access German Visions of India, 1871–1918 by P. Myers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Protestant and Catholic Champions and Their Visions of India

Chapter 1

Restoring Spirituality

Buddhism and Building a Protestant Nation

On the shores of the Ganges the reader will now want to follow me, even if only by way of a sketch, in order to be a witness to one of the most marvelous acts of emancipation in the realm of religion.

Christian Hönes, Deutsche Zeit-und Streit-Fragen (1877)1

CHRISTIAN HÖNES, IN THIS SPEECH DELIVERED IN Basel in February 1877, impels his audience to bear witness to what he viewed as one of the most remarkable religious revolutions in history—what Friedrich Max Müller, the renowned German Indologist at Oxford, described as “the greatest event in our eventful century.”2 As we might expect, Hönes, a Protestant assistant pastor (Diakonus) in Weinsberg, a town in southwestern Baden-Würtemburg, foresaw this revolution in anticipation of India’s pending Christianization, yet many other German intellectuals heeded Hönes’s call with vastly different motivations for exploring India’s revolutionary transformation and in various ways—academic study, travel reports, and essays. During the early years of the Kaiserreich, for instance, some German intellectuals turned to Indian Buddhism as a sounding board for their own cultural reflections and spiritual disputations. Paul Wurm (1829–1911), Protestant deacon in Calw, also in Baden-Würtemburg, and later theologian and Lehrer at the Missionshaus in Basel, commented in 1880:3 “The philosophical atheism of our day, the pessimism of a Schopenhauer and v. Hartmann, warmed up our species for the wisdom of the Buddha.”4 Viewed from this perspective, Hönes’s plea also points implicitly to the spiritual void that so many intellectuals gradually sensed during the early decades of the Kaiserreich and from which many sought relief through their reformulations of Indian traditions. Thus despite the more caustic assessment of Eastern influence on Western thought by some, other German thinkers during the early period of the Kaiserreich—also in the midst of contemplating their newly forged nation and victory over France in 1871—constructed a vision of India, and particularly of Buddhism, through which they could negotiate their own religious, political, and social quandaries. Let us begin with a brief look at the origins of that interest in Buddhism and what German readings of the revolutionary Buddha portended for the first part of this book.

The Discovery of the Buddha

In 1844, after years of diligent work translating Sanskrit texts, the eminent French scholar Eugène Burnouf (1801–52), published Introduction à l’histoire du Buddhisme indien.5 The book’s publication proved to be a watershed moment in placing Buddhism on Europe’s intellectual landscape.6 Burnouf’s text served as a fundamental frame of reference for renowned Sanskrit scholars, such as the aforementioned Müller, and remained a foundational text for generations of scholars. Importantly, Burnouf’s work delineates the history of Buddhism as it had evolved from the teachings and life experiences of its founder, Guatamo Buddha.7 Burnouf’s emphasis on the personal deeds of the Buddha and his influence on Buddhism’s beginnings and further blossoming in India—a hermeneutical angle that had been unfurled through various Sanskrit and Pali translations of such texts as the Lalita Vistara—proved critical for how Europeans framed their scholarly work.8 The European “discovery of Buddhism,” as Tomoko Masuzawa explains, “was therefore from the very beginning, in a somewhat literal and nontrivial sense, a textual construction; it was a project that put a premium on the supposed thoughts and deeds of the reputed founder and on a certain body of writing that was perceived to authorize, and in turn was authorized by, the founder figure.”9 The importance of the Buddha as principal—a revolutionary figure and religious initiator—had two significant consequences for ensuing intellectual work on religious history in Germany. First, it proved conducive for direct comparisons to the life of Jesus, which became a threatening mode of inquiry for some and a stimulating enterprise for others as European intellectuals attempted to map the world’s religions. Second, the Buddha, who was viewed frequently as a revolutionary instigator, became easily deciphered by many German thinkers as leader of an avant-garde religious group that served as the catalyst for ending the dominance of the spiritually rigid and politically unyielding Brahmin priests in ancient India. These two frames of reference—one comparative religion, the other investigating the seeds of socioreligious revolt—would, as we shall see, prove opportune for Protestant German India experts who, after the failed 1848 revolution, sought to reassert their spiritual and political identities vis-à-vis the Lutheran establishment but also a different priestly class—Catholics—in the Kaiserreich.10 To put it more boldly, the picture drawn of the Buddha and of Buddhism by Protestant German thinkers, particularly after 1871 and during the 1880s, offered a unique means to rehearse a more assertive Protestant vision for the emerging German nation during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Yet in the world of Protestant visions a revitalized German community is explicitly derived from the rejuvenation of individual spirituality, a subject that will receive more attention shortly. For now, let it suffice to say that the emerging German nation requires a new spirit instilled by the heroic acts of “world historical figures,” to put it in Hegelian terms, whose spiritual rejuvenation redounded to the benefit of the community. Specifically, new frames of reference for achieving individual spirituality were needed to provide the requisite cultural impulses for social and political revolutions—to constitute the newly formed German nation. The young Indologist Leopold von Schroeder modeled that Protestant hero in his five-act Buddhist-conversion Trauerspiel from 1876, König Sundara.

Leopold von Schroeder’s Quest for Spiritual Meaning and Buddhism

In 1872, as the newborn Second Reich was still basking in its victory over France, Michael Baumgarten, professor of Lutheran theology in Rostock, summarizes his vision of a revitalized Protestant Church in Bismarck’s Germany:11 “If we take stock from all this, then the result is that the Church, for which Luther struggles, the more it is grounded in the freedom of spirit, the more capable and determined it is to effect in the people a moral rebirth, which wants to free the medieval State from its unnatural fetters and to build a Kingdom, in which one should recognize a preliminary stage of God’s Kingdom.”12 Here Baumgarten calls for a revival of Luther’s reformatory power to free the emerging German nation from the fetters of Catholic medievalism and implores the new state to assert political and religious precepts that would work in perfect harmony. Significantly this newfound Germany, according to Baumgarten, constitutes a preliminary stage that precedes God’s Reich—an unambiguous link between denominational objectives and the prerogatives of the nation.

Importantly, the link between the Protestant institutional agendas and the political aims of the nation makes up only part of the story. For any Protestant, Baumgarten’s call for a rebirth of ethical standards (sittliche Wiedergeburt) necessarily points to the rejuvenation in individual moral behavior as well—a link that derives from Protestantism’s ingrained emphasis on individual fulfillment and salvation. In 1862, for instance, the career Prussian civil servant Theodor Schultze, who at the time had yet to break out of his strict Protestant upbringing’s ideological shackles to become an important Buddhist acolyte (Chapter 3), maintained that human beings were created solely “to seek fulfillment” as God’s children.13 Rudolf Seydel, one of our India experts to be discussed in more detail shortly, elaborates more explicitly in a lecture to the Deutsche Protestantenverein in 1871: “Every individual must abandon oneself to the Godly within his soul, must create a space for heavenly salvation in his inner self: otherwise the liberational effect that redeems from sin and relieves the pressure of past guilt cannot reach him.”14 In the Protestant model for attaining salvation, as these examples demonstrate, the burden of redemptive proof lies squarely on the individual’s shoulders.

Yet importantly for these Protestants, individual salvation always remained unambiguously linked to the cultivation of community consensus. In other words, community rejuvenation depends on a revitalized individual spirituality. In Baumgarten’s essay, for instance, he trumpets, “Protestantism is grounded inwardly or facing God in the freedom of the spirit itself, which also lives in the Church; externally or in the world it is the moral center of power, which leads and raises the complete life of the people to a free Nation and towards God’s kingdom.”15 Here Baumgarten subtly affirms that the reconstitution of community standards is dependent on the blossoming of the individual spirit in the Church. To put it another way, the reconstitution of the community’s frames of reference implicitly depends on the individual pursuit of salvation and quest for a stable model of spiritual cohesiveness.

As a result, confessional aspirations and the assertion of Prussian political perquisites during the era cannot be easily decoupled from the spiritual discord that so many Protestant India experts of the era acutely sensed, vigorously debated, and spiritedly sought to resolve.16 Their attempt to forge new narratives of spiritual identity in the community must be acknowledged as an underlying factor in how they framed and asserted their confessional and political agendas in a vision of Buddhism.

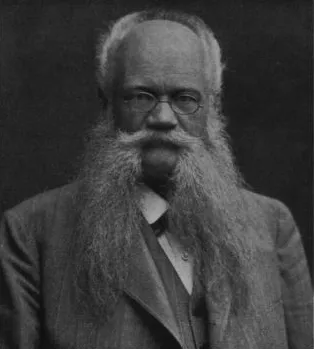

Such links between Prussian political perquisites for the emerging Reich, confessional objectives, and the longing for spiritual harmony resonate clearly in the early work of von Schroeder (1851–1920), an important intellectual player in the emerging field of Indology.17 Born among the German minority in Dorpat (Tartu), Estonia, von Schroeder discovered early in life his passion for Sanskrit. Beginning in 1875 in Leipzig, he studied the classical Indian language under Hermann Brockhaus and Ernst Kuhn and moved to Tübingen later that year where he continued his studies under the renowned Veda specialist Rudolf Roth. Shortly thereafter he landed his first position as a docent in his home city of Dorpat, where he completed his Habilitation in 1877. Two decades later in 1895, motivated in part by the growing “Russification” movement, von Schroeder took a position in Innsbruck, Austria, arranged by the University of Vienna Indologist Georg Bühler, who von Schroeder eventually replaced in 1899 as a nontenured professor after Bühler’s death.18 Von Schroeder remained in Vienna until his death in 1920.

Today von Schroeder is perhaps most well-known as a Wagnerian and a friend and supporter of the racist-Aryanist Houston Stewart Chamberlain, whom we have already briefly discussed. Von Schroeder’s book Arische Religion (1914–16), published toward the end of his life, and other essays, particularly from his time in Vienna, link his thought to emerging biological racism, völkisch cult movements, and eventually National Socialism.19 Yet his youthful literary imagination offers a different impression and provides unique insight into an emerging paradigm for negotiating the era’s religious and political dilemmas through the constructed image of a cultural Other: Indian Buddhism. Specifically, König Sundara’s plot, for instance, conveys spiritual strife, denominational partisanship, and revolutionary political agendas—issues that occupied von Schroeder and other thinkers during the early Kaiserreich.

Figure 1.1 Leopold von Schroeder.

Source: Frontispiece from Leopold von Schroeder, Lebenserinnerungen, ed. Felix v. Schroeder (Leipzig: H. Haessel Verlag, 1921).

Importantly, the play was written, by von Schroeder’s own admission, during a time of personal religious exploration and the tribulations of love. The latter requires little comment, but the former was a common feature of the current intellectual mind-set as German thinkers responded to the era’s sense of spiritual discord. According to von Schroeder, for instance, in an essay from 1878, the quest to define and attain something higher—more spiritually meaningful—was an underlying feature for virtually all intellectuals of the era: “Everywhere we recognize in a portion of the people a grappling and striving, a yearning for something higher.”20 These sentiments had led him early in his life to the study of Sanskrit, which became his professional calling. Yet his studies of ancient Indian religious traditions always remained intricately linked to his personal attempt to define his spiritual faith—a task that seems to underlie his entire life’s path and work. In fact, his academic work as well as his more general essays and literary production on Indian culture and religious traditions reveal a recurrent underlying theme: the human endeavor to define and attain a higher sense of meaning in a mundane world in which the traditional sources of intellectual identity seemed under stress.

As a result, von Schroeder’s search for spiritual meaning becomes especially palpable in his recollection of the period in which the play Sundara was composed. In his autobiography, written during the later decades of his life and published posthumously by his son Felix von Schroeder in 1921, von Schroeder corroborates this assessment. In his account of his youth, he frequently refers to the influence of religion in his life’s path and how it directly impacted his work and personal relationships during those early years. He recalls, for instance, his precocious marriage prospects, in which he laments a strained marriage proposal that would later end with his fiancé breaking off the engagement. Besides his unpromising financial outlook, von Schroeder explains one other difficulty with his promise as a future husband: “In addition, my rejecting, critical, even unbelieving standpoint vis-à-vis Christianity from back then found little approval from the Mühlenschen family. Also my Buddhist tinted ‘König Sundara’ was not received with understanding.”21 Here, in reference to Sundara, von Schroeder links the play in hindsight with his own search for spiritual meaning and his youthful Buddhist convictions. In his autobiography he recalls his early stance toward the Christian Weltanschauung: “As I wrote König Sundara in Tübingen, I stood completely distanced from it, was more likely to be called Buddhist than Christian.”22 Von Schroeder had revised his spiritual identity, at least temporarily, in his image of India’s social and religious reformer Guatamo Buddha.

Thus in a certain sense Sundara exemplifies the beginning of von Schroeder’s lifelong quest to update his religious faith in an era of fundamental challenges for any social scientist confronting the conflicts between new social science and, for many, older, ineffectual religious traditions. Again reflecting in his autobiography, von Schroeder contextualizes the dilemma in more explicit terms: “I had lived with the idea of standing at the height of modern culture, which seemed irreconcilable with Christian beliefs. The Weltanschauung of our classics, our philosophers, our great men of science seemed superior to one based on Christian belief, even in fact the only one compatible with progressive thought. But I had to experience, that this way of viewing the world and life began to seem more and more internally hollow and dissatisfying.”23 Though unmistakably distorted by his later reembrace of Christianity (a subject to be discussed more thoroughly in Chapter 4), von Schroeder’s assessment palpably manifests how the conflict between new humanistic inquiry (social science and biblical criticism) and religious identity underpinned his academic and literary work—as we will explore throughout this monograph, progressive history as von Schroeder, Seydel, and others constructed it was never simple. Moreover, this tension is emblematic for a generation of intellectuals who engaged with Indian religious traditions and culture as they attempted to reconfigure their political and religious identities. Thus a closer look at how this German intellectual analyzed and interpreted Buddhism in his König Sundara can provide deeper insight into the ongoing debates on religious meaning, denominational conflict, and the shifting social-scientific paradigm for assessing knowledge of the human being during the Kaiserreich. That is, Sundara illustrates vividly how von Schroeder’s engagement with Indian religious traditions embodies an attempt to reconstitute spirituality under threat and mirrors the cultural, social, and political debates of the 1870s.

The Transforming Power of the Buddha: Christianity versus Sundara

Sundara is set at the height of Brahmanic power in India.24 The principal protagonist is the young King Sundara, who belongs to a long line of honorable and respected monarchs. From the opening scene, trouble st...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography