eBook - ePub

The Moscow Pythagoreans

Mathematics, Mysticism, and Anti-Semitism in Russian Symbolism

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Moscow Pythagoreans

Mathematics, Mysticism, and Anti-Semitism in Russian Symbolism

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In Russia at the turn of the twentieth century, mysticism, anti-Semitism, and mathematical theory fused into a distinctive intellectual movement. Through analyses of such seemingly disparate subjects as Moscow mathematical circles and the 1913 novel Petersburg, this book illuminates a forgotten aspect of Russian cultural and intellectual history.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Moscow Pythagoreans by Ilona Svetlikova in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Origins of the Moscow “School”: N. V. Bugaev

Abstract: Materials preserved in N.V. Bugaev’s archives allow us to explore the origins of the ideology of the Moscow philosophic-mathematical school and, in particular, the anti-Semitic elements of this ideology. Bugaev’s Foundations of Evolutionary Monadology (1893), as well as Belyĭ’s Symbolism (1910), are considered within the framework of the European “Aryan renaissance.”

Svetlikova, Ilona. The Moscow Pythagoreans: Mathematics, Mysticism, and Anti-Semitism in Russian Symbolism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. DOI: 10.1057/9781137338280.

Bugaev’s library

“Pythagore le pensait déjà: les mathématiques sont á la base de tout.” This phrase, which I recently came across in a Russian schoolbook for French, sounds so banal that it could pass without remark. This makes it difficult for us to pick up such a formula appearing in a different historical context where it in fact constituted a matter of intense reflection. This marks a sharp difference: for us such a phrase is almost empty of meaning, being a part of common discourse, whereas at the time of its historical reemergence it acquired new significance now eluding us. An apparent coincidence in form (the Moscow mathematicians would have subscribed to the phrase from the schoolbook in its entirety) masks a profound divergence: a truism in one case, and a matter of deep reflection in the other. In the case of Bugaev’s disciples, the phrase’s revival was partly contingent on the political element of the Pythagorean tradition, both historically (the Pythagorean school actively participated in political life) and logically: if we are talking of mathematics as a foundation of all human knowledge, that implies politics as well.

The papers from Bugaev’s archives point to the origins of the renewed interest in the idea of a universal significance of mathematics.1

1

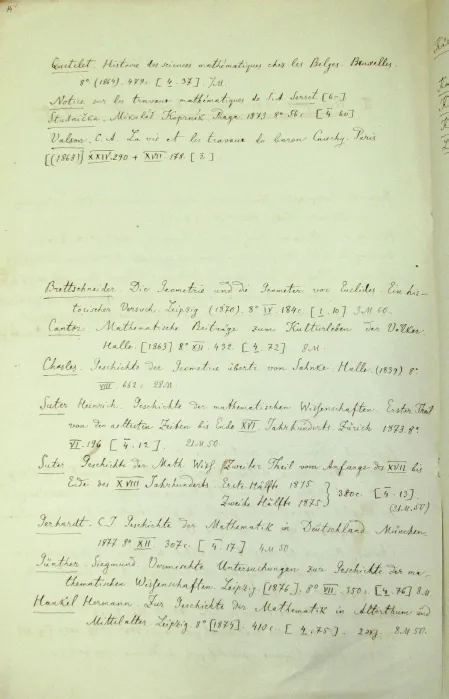

One of the most valuable documents preserved in Bugaev’s archives is the catalog of his library.2 It was drawn up at the beginning of the 1880s, when the collection ran to 1600 volumes, and Bugaev still had 20 years ahead of him to add to the collection. There is, however, every reason to believe that the library’s structure remained unchanged. The catalog consists of 28 sections, ranging from mathematics and other sciences to sociology and psychology.

The last section of the catalog is that of the belles-lettres. Not only is it the very last, but also the smallest section, comprising only seven books—a strange assortment at that, with Dante and Goethe juxtaposing authors unknown even to most historians of literature.3 This seems to point to Bugaev’s lack of any pronounced interest in literature, and also has implications for Belyĭ, who grew up in this library. He manifested the same passion as his father for a broad spectrum of knowledge, according to the lists of books he read, among which works of fiction and poetry are comparatively rare.4 Thus, his father’s library catalog indicates why commentary to Belyĭ’s work involves us in intellectual history going far beyond the realm of literature.

Figure 1.1 A page of the catalog of N. V. Bugaev’s library (ORK i R NB MGU)

2

Despite the apparent incongruity of some sections, there is nothing arbitrary about the catalog taken as a whole. Bugaev seems to have collected his library in a systematic way. It is not the library of a mathematician who is focused exclusively on his field, nor does it seem to be one of a dilettante jumping at random from one interest to another.

Among Bugaev’s papers, there is a copybook containing his notes taken from the second edition of Montucla’s classical Histoire des mathématiques (1799–1802).5 It is important that Bugaev includes in his notes what many mathematicians would have omitted as extraneous to mathematics as such. In particular, he is attracted to what Montucla writes in the beginning of his history about the great respect that mathematics enjoyed amongst the ancients. There are notes (admittedly not very accurate) revealing Bugaev’s interest in the following passage:

Les mathématiques furent toujours accueillies avec une estime singulière par les philosophes les plus respectable de l’antiquité. Nous remarquerons en effet que tout ceux dont la doctrine et les mœurs furent les plus parfaites, cultivèrent ces connoissances, ou du moins en firent cas. <…> Ainsi pensèrent, pour ne citer que les plus célèbres, Thalès, Pythagore, Démocrite, Anaxagore, et tous les philosophes des écoles Ionienne et Italique; Platon enfin, Xenocrate, Aristote, &c. Personne n’ignore que les premiers de ces philosophes contribuèrent de tous leurs soins aux progrès qu’elles firent dans la Grèce; que Platon fut un des plus habiles Géomètres de son temps, et que ses ouvrages sont remplis de traits honorables pour les mathématiques. Quel cas ne témoignoit-t-il pas faire de la géométrie, lorsque questionné sur les occupations de la divinité, il répondit qu’elle géométrise continuellement, c’est-à-dire, sans doute, qu’elle gouverne l’univers par des lois géométriques?6

This passage is abbreviated in Bugaev’s notes, along with Montucla’s reference to mathematics as the fundament of the education and philosophy of the ancients, and Hippocrates instructing his son about the usefulness of mathematics for medicine. Bugaev also copied out a list of later philosophers who were also mathematicians, as cited by Montucla.7 Clearly, these are the notes of an enquirer interested not only in mathematics but also in its interrelations with other disciplines (the universality of Leibniz fascinated Bugaev for years8), and who is attracted by the idea of the primary importance of mathematics among all the disciplines.

Bearing this in mind, Bugaev’s library was an accurate expression of his intellectual preferences. It is unlikely that in collecting books he merely strove after general erudition, without being guided by his thinking about mathematics. It would rather seem that the variety of subjects to be found in the catalog of his library reflected his thoughts on mathematics: ruminations on the universal significance of mathematics presupposed interest towards other disciplines. From the point of view of a “universal mathematician,” all other disciplines were linked to his own domain, meaning that all of them were to become mathematical:

To find measure in the domain of thought, will and feeling—this is the task of the contemporary philosopher, politician and artist.9 <…> From the sphere of undefined, limitless, animal instincts, man is striving, with the help of number and measure, to rise to the ideal condition of having full power over outer and inner nature, of establishing harmony and esthetical feeling in every manifestation of the human spirit.10

Among Bugaev’s teachers, I have found only one manifestation of comparable beliefs in the power of mathematics. In his speech O vliîanii matematicheskikh nauk na razvitie umstvennykh sposobnosteĭ [On the influence of mathematical sciences on the development of mental faculties], delivered in 1841, Nikolaĭ Dmitrievich Brashman (1796–1866) referred to some of the above cited examples of the importance of mathematics, adduced by Montucla and copied by Bugaev.11 There may have been some discussions in the Moscow mathematical circle that influenced Bugaev’s interest in mathematics as a fundamental discipline of universal import. However, apart from Brashman’s short speech there is little evidence as to their nature.12

3

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the idea of the potential universality of mathematical knowledge does not appear to have excited much general or professional interest. If, for comparison, we open the article Géometre by d’Alembert in the Encyclopédie, published a year before the above-mentioned book by Montucla, we will find a similar train of thought enthusing over the universal relevance of mathematics. The trend established in the seventeenth century of charging mathematics with meanings going beyond mathematics itself, to see it as a foundation for education and a vehicle for moral and social perfection, that is, to impart an ideological role to mathematics, was still well alive in the eighteenth century. According to d’Alembert, the study of geometry precedes the spread of enlightenment: “C’est peut être le seul moyen de faire secoüer peu-à-peu à certaines contrées de l’Europe, le joug de l’oppression et de l’ignorance profonde sous laquelle elles gémissent.”13 Thus, mathematics acquires an ideological character, p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Belys Petersburg and Moscow Mathematicians1

- 1 Origins of the Moscow School: N.V. Bugaev

- 2 The Moscow School: P.A. Nekrasov

- 3 P.A. Nekrasov: Theory of Probability(1912)

- 4 Some Other Members of the School

- 5 The Pythagoreanism of the Moscow School

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1: Geometrical Meditations of the Senator

- Appendix 2: Rhythm

- Appendix 3: The Sentiment of Nature

- Select Bibliography

- Index