![]()

1

Introduction

Anyone following the ongoing problems of the Doha Round of trade talks might be forgiven for thinking that trade politics has become a sideshow in the international political economy. Even as the multilateral negotiations have gone through multiple deadlocks, the world has experienced a flurry of preferential trade agreements (PTAs) of various shapes and sizes. The World Trade Organisation (WTO) currently lists over 200 such agreements as being in force (WTO 2013). This broader trend towards seeking discriminatory trade deals has also meant that the agenda of ‘behind-the-border’ liberalisation – agreement on issues such as the regulation of trade in services, government procurement and intellectual property rights – has grown in prominence; ‘deep’ liberalisation is easier to negotiate between preferred partners. For advocates of free trade, long frustrated with the slow pace of multilateral negotiations, this is seen as a positive development. Writing on one of the most significant of these agreements to be proposed – a free trade agreement (FTA) between the European Union (EU) 1 and the United States (US) – The Economist (2013) was to proclaim that ‘it could anchor a transatlantic economic model favouring openness, free markets, free peoples and the rule of law over the closed, managed visions of state capitalism’. For the EU, the world’s single largest trader (see Eurostat 2013: 94), the trade deal with the US substantiates the message of the epigraphs above: the pursuit of free trade is explicitly linked to European economic performance. Given the economic crisis currently rocking the continent, which is not only causing considerable economic hardship but has also constrained the public purse, trade opening is seen as a cheap means of generating much sought-after ‘growth and jobs’. This is not new. Ever since its 2006 ‘Global Europe’ communication – which led the EU to abandon an informal and self-imposed moratorium on new FTAs it had adopted in order to underscore its commitment to the Doha Round – the EU has seen the pursuit of PTAs as the means for delivering the sorts of market access gains that it allegedly needs to engender economic prosperity.

This book is about the drivers of the 2006 ‘Global Europe’ communication and the sorts of agreements it has spawned – most notably with South Korea, which represents not only the first completed FTA to come out of ‘Global Europe’ but is also widely seen as the EU’s most ambitious commercial agreement so far. ‘Global Europe’ is seen as a key moment in EU trade policymaking, leading the EU to actively embrace preferential market opening as the most significant instrument in its offensive trade arsenal. In the communication, the Commission – or more specifically its Directorate-General (DG) for Trade 2 – argued that while multilateral trade liberalisation remained the EU’s ‘priority’, other, bilateral avenues had to be urgently sought (European Commission 2006g). In the context of a (then already) stagnating Doha Round this read like a wholesale espousal of bilateralism and went beyond the more ad hoc bilateralism of previous years, which had seen the EU sign agreements with Mexico, Chile and South Africa while still prioritising the multilateral trade route (what became known explicitly as the ‘multilateralism-first’ policy under Trade Commissioner Pascal Lamy; see Lamy 2002: 1401). Crucially, ‘Global Europe’ saw the EU target the emerging economies of East Asia. 3 These could provide significant market opportunities for its (competitive) upmarket exporters which the multilateral trading system was failing to deliver – especially as such countries were unwilling to discuss the sorts of regulatory issues that the EU had shown a keen interest in pursuing during the Round – and which the EU’s commercial rivals (especially the US) were already pursuing through their own FTA agendas.

In this book I also consider the broader impact of ‘Global Europe’ on the European and international political economies. As ‘Global Europe’s’ sub-title – ‘Competing in the World’ – made clear, it explicitly linked Europe’s economic well-being to its ability to compete in the global economy. In doing so, policymakers were invoking the ideas embodied by the Lisbon Agenda of competitiveness. This overarching strategy document, announced in 2000, aimed to transform the EU into ‘the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world, capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs’ by 2010 (European Council 2000). Much in the same way, ‘Global Europe’ promised to deliver ‘growth and jobs’ through ‘activism in creating open markets and fair conditions for trade abroad’ (European Commission 2006g: 6). This is important for three reasons. Firstly, the EU has sought not only to serve the interests of upmarket exporters, but has increasingly done so at the expense of other, hitherto protected sectors. The second, related point is that trade policy plays an increasingly important role in the discourse of economic policymaking within the EU, given the explicit linkages between ‘internal’ and ‘external’ competitiveness first stressed by ‘Global Europe’. This is reinforced by the increasingly regulatory nature of the liberalisation sought by the EU. Thirdly, this mantra of competitiveness has ever more permeated the EU’s trade relations with developing countries, especially with the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) group of states. Not only has a renewed interest in the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) being negotiated with the ACP dovetailed with the arrival of ‘Global Europe’, but increasingly, the Commission has pushed for these agreements to feature regulatory liberalisation that goes beyond WTO disciplines. This is justified on the basis that it enhances the economic prospects of developing states. The specific provisions, however, bear a striking resemblance to the texts of the EU’s ‘Global Europe’ FTAs despite policymakers insisting that the EPAs lie at the heart of its international development (rather than commercial) strategy.

The EU continues to be wedded to an aggressive strategy of preferential market opening since the start of the Financial and Eurozone Crises. But, despite the continued impact of Global Europe, to my mind the true significance of EU trade policy has long been masked by its treatment – or more precisely, the relative lack thereof – in the International Political Economy (IPE) literature. Compared to the plethora of works written by political economists on trade policymaking in the US, the study of EU trade policy has been largely neglected (although this is beginning to change, see Poletti and De Bièvre 2013). Instead, the study of the EU’s commercial relations and trade policymaking processes has generally been confined to the narrower field of EU Studies. Here, rather than consider the wider implications of EU trade governance within the international political economy, the focus has largely been on the institutional determinants of policymaking, the implicit argument being that this is justified by the EU’s sui generis trade governance structure; the shift from ‘multilateralism-first’ to ‘Global Europe’ and the increasingly entwined ‘developmental’ and ‘commercial’ trade agendas of the EU, however, occurred in the absence of any institutional change to the EU’s trade governance structures. Similarly, an almost exclusive focus on the material drivers of (EU) trade policy has obscured some of the deeper drivers of policymaking; the distributive politics of the liberalisation implied by ‘Global Europe’ cannot be explained by the allegedly unique institutional insulation of EU trade policy nor be simply ‘read off’ the material interests of societal actors (as in endogenous trade policy accounts). While I am not saying that rationalist approaches have nothing to offer the student of trade politics – I explicitly draw on such literature for important insights into the behaviour of interest groups – in this book I also consider the role of language and ideas. More concretely, such an approach helps to explain three inter-related puzzles raised by conventional understandings of EU trade policy: why was there a shift to bilateralism as implied by ‘Global Europe’; why did this entail significant economic restructuring and why did it bring about the increased entwinement of the EU’s ‘developmental’ and ‘commercial’ trade agendas?

Parsons’ A Certain Idea of Europe (2003) contends that a set of specific ideas held by French elites – and their subsequent institutionalisation – explain the shape of European integration. Not entirely unlike him, my argument focuses on the role that a set of particular ideas about the EU’s place within the world have had on the conduct of its trading relations. Promoted by trade policymakers in the European Commission, the notion that the EU had to adapt to the competitiveness challenges of the global economy and service the interests of exporters – what could be called ‘a global idea of Europe’, as in the subtitle of this book – is one which has had a considerable impact as part of the neoliberal drift of EU trade policy. In this sense, I join a group of ‘critical IPE’ scholars writing about the neoliberal shift (away from ‘embedded liberalism’) in EU policy in more specific policy domains, such as competition policy and corporate governance (Buch-Hansen and Wigger 2011; Horn 2011). In contrast to such largely neo-Gramscian perspectives – which have been criticised as not sufficiently attuned to the role of specific agents and ideas, especially as they are situated within a broader literature on the increasing marketisation implied by the ‘relaunch of European integration’ in the 1980s (see Gill 1998; van Apeldoorn 2002; Cafruny and Ryner 2003) – I am explicitly seeking to craft a constructivist IPE perspective on EU trade policy. Specifically, I focus on the role that particular agents (DG Trade, the Trade Commissioners and the constituency of exporters) and ideas play in constructing and reproducing neoliberalism in this specific policy field. Moreover, constructivists have not only studied the broader shift from ‘embedded liberalism’ to neoliberalism (for example, Blyth 2002) – which is not so much the focus of this book – but have also developed arguments on the strategic agency of supranational actors in the context of European integration that bear some resonance to my own (for instance, Rosamond 2002; Jabko 2006). These scholars show that ideas about competitiveness and the market have been deployed by the Commission as a compelling set of arguments to constrain other actors (see Hay and Rosamond 2002), such as those who might be opposed to trade liberalisation and the economic restructuring it implies. To rephrase Wendt’s (1999) much-cited line, trade is what (these) actors (choose to) make of it. Moreover, I find that such ideas continue to hold sway in the current economic context – although their future is perhaps less certain – adding to discussions about the ‘resilience’ of neoliberalism since the start of the Financial and Eurozone Crises (see Crouch 2011; Schmidt and Thatcher 2013).

In order to situate my argument within current debates on EU trade policy, the next section provides an overview of such perspectives and their tendency to focus on the institutional determinants of trade policy. This section also briefly discusses the institutions of EU trade policy. I then offer an overview of the book’s empirical focus and constructivist argument. The penultimate section serves as an outline to the remainder of the book and the chapter concludes with a short note about the primary sources used.

The (overstated) role of institutions in EU trade policy

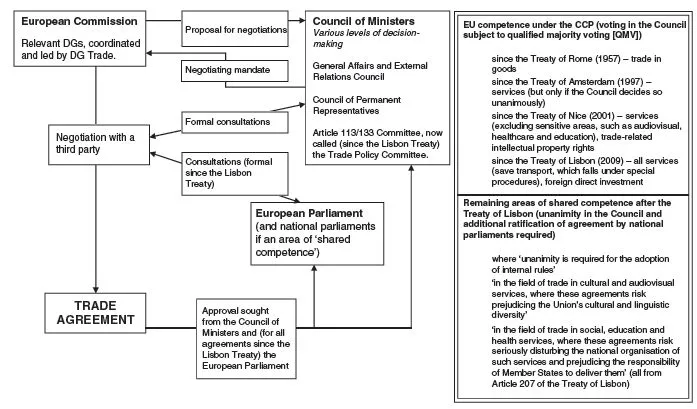

The EU Studies literature on trade policy has largely adopted a rational choice institutionalist approach that sees institutions in a narrow sense as ‘the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction’ (North 1990: 3; see also Hall and Taylor 1996). 4 This has meant a focus on the formal institutional machinery of EU trade policy, which is established in the various EU Treaties (see Figure 1.1; Woolcock 2012: 51–61). Most of it falls under the so-called Common Commercial Policy (CCP), originally set up by the Treaty of Rome in 1957. In the original CCP, the Member States had delegated negotiating authority for trade agreements with third parties in goods to the European Commission. That being said, approval from the Council of Ministers was still required to initiate and conclude any trade deals, while Member States also monitored the Commission via a specialised Council working group. Since the Treaty of Lisbon (which came into force in December 2009) this is known as the Trade Policy Committee, but was formerly known as the Article 133 and (before Amsterdam) the Article 113 Committee, after the article in the Treaties establishing the CCP. The Treaties of Amsterdam, Nice and Lisbon have since increased the number of trade issue areas that – as ‘EU competence’ – fall under the purview of the CCP, such that now only very few areas are subject to ‘shared competence’ between the EU and the Member States (where different policymaking procedures arise, see Figure 1.1). Since the Treaty of Lisbon, the European Parliament (EP) also has the prerogative of having to assent to all trade agreements (as well as being formally consulted during trade negotiations, where previously its involvement was at the Commission’s discretion). Most of the existing research on EU trade policy written so far has, however, worked within the older institutional set-up privileging the Commission and Council.

Figure 1.1 An overview of the formal EU trade policy process and the evolution of competences

Sources: Adapted from Woolcock (2010b: 390), Figure 16.1; the figure also draws on relevant EU Treaties.

Key to much of this research is the so-called ‘collusive delegation’ argument (Meunier and Nicolaïdis 1999; Meunier 2005; Woolcock 2005). Its basic proposition is that the delegation of trade policymaking authority from national governments to the supranational Commission in the Treaty of Rome was intended to ‘insulate the process from protectionist pressures and, as a result, promote trade liberalisation’ (Meunier 2005: 8). Taking this as a starting point, most scholars have focused on two aspects of EU trade policy: the nature of interest mediation within a ‘multi-level’ polity and the effects of inter-institutional conflict resulting from the delegation of trade policymaking authority. In the first school of thought – borrowing from the work on ‘multi-level games’ of Moravcsik (1998) and Putnam (1988) – EU trade policy has been conceptualised in terms of three distinct arenas of decision making: the domestic level (inside Member States), the supranational EU level (the Council) and the international level of negotiation with third parties (see Collinson 1999; for applications, see Young 2002; Meunier 2005). The focus here has generally been on the institutional parameters shaping the aggregation of diverse national interests into a single European position – such as the nature of voting rules in the Council (Young 2006: 12). For its part, research that has explored the delegation of trade policymaking authority in the EU has mostly adopted a methodology known as principal–agent analysis (PA) (see Pollack 2003; for applications to trade policy, see Meunier 2007; Elsig 2007). The PA approach is essentially concerned with the delegation of a task (in this case trade policy authority) from a principal (the Council of Ministers) to an agent (the Commission) and the various control mechanisms that the former can employ to ensure that the latter acts according to the mandate that has been set. Similarly, scholars have also studied conflict between different DGs with responsibility for different aspects of trade policy (for example, Larsén 2007). This builds on researc...