eBook - ePub

Theatre and Ghosts

Materiality, Performance and Modernity

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Theatre and Ghosts

Materiality, Performance and Modernity

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Theatre and Ghosts brings theatre and performance history into dialogue with the flourishing field of spectrality studies. Essays examine the histories and economies of the material operations of theatre, and the spectrality of performance and performer.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Theatre and Ghosts by M. Luckhurst, E. Morin, M. Luckhurst,E. Morin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Theatergeschichte & -kritik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Ghosts, Stage Adaptation and Technology

1

Charles Dickens and the Invention of the Modern Stage Ghost

Marvin Carlson

‘Marley was dead: to begin with’ is the opening sentence of the most famous short story in the English language, Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, still today an inevitable component of the Christmas season, both as a reading and in countless theatrical and film adaptations.1 This beloved story – a great success from the outset – was the first of a series of literary meditations on both Christmas and ghosts by the popular English author, and these works together greatly contributed to the Victorian image of Christmas, to the Victorian image of ghosts, and, as we shall see, to the Victorian interest in stage machinery, one of the most striking uses of which was the creation of ghost effects.

So familiar is the opening sentence of A Christmas Carol that we are scarcely likely to notice how closely it connects with contemporary theories of representation, which have also pointed out that representation begins with death. In the words of Herbert Blau, ‘If repetition is fundamental to performance, it is – after all or to begin with – death which rejects pure presence and dooms us to repetition.’2 The traditional symbolic representation of the repetition, this unavoidable return, is the figure of the ghost. Although Dickens both literally and figuratively begins his story with an evocation of death, he goes on to evoke – as does Blau – the most famous of deaths initiating a story, which involves the appearance of the most famous of literary ghosts, that of Hamlet’s father. Although deaths, both actual and potential, appear in Dickens’s story from beginning to end, it is less death itself than its emblem, the ghost, that dominates the tale. In his preface, Dickens called the story a ‘Ghostly little book,’ which sought ‘to raise the Ghost of an idea.’3 The title page of the first edition, in 1843, bears the subtitle ‘A Ghost Story of Christmas.’

It is peculiarly appropriate that both Hamlet and A Christmas Carol, the two most frequently produced theatre pieces in the English-speaking theatre, are ghost stories. In The Haunted Stage, I have developed in some detail the importance of haunting in the theatre, truly a house of ghosts, where the restless spirits of the past trouble equally the Greek house of Atreus and the modern houses of Ibsen and O’Neill. In that book, however, I argued that the theatre’s age-old obsession with ghosts and haunting reflected not just a particularly exciting and mysterious subject but, much more deeply, something in the dynamics of the creation and reception of theatre itself, both processes remaining profoundly involved with repetition and memory.4 Not only does theatre repeat specific stories and characters more often than any other narrative form, but within its presentation, returning audiences regularly see objects and especially bodies that they have seen before, albeit in different contexts. The result is that theatre productions are almost always ‘haunted’ by the memories of other productions of the same work, the same story, the same elements, the same actors appearing in other works. I have called ‘ghosting’ the audience’s inevitable recognition of an emotional and intellectual participation in this process.5 In this chapter I will focus literally on stage ghosts, particularly on the stage ghosts of Dickens, their ghostly ancestry and ghostly progeny, and not on the more abstract and general process of theatrical ‘ghosting,’ although that more abstract process is always at work in reception – especially in the theatre, as Dickens was well aware.

Dickens’s literary ghosts

The novella The Haunted Man, as its title suggests, is an even more haunted work than its better-known predecessor, A Christmas Carol – haunted indeed in large part by that predecessor, which had already become one of Dickens’s best-loved works internationally. This was true both in the study and in the theatre, because even before the appearance of A Christmas Carol Dickens was a well-established name on the London stage. Popular playwrights such as W.T. Moncrieff and Edward Stirling had, during the decade before 1843, produced more than sixty works based on The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby. A Christmas Carol began a new wave of such adaptations, at least eight of which appeared in the first two months of 1844. America followed soon after, and before the novella was a year old, it had been staged sixteen times in London and New York, a record surpassing that of any previous Dickens work.6

For the next four years Dickens sought to extend his success by regularly producing a Christmas novella, each of which immediately inspired a number of stage versions. All had some supernatural touches, but only the last of this series, The Haunted Man, was as centrally concerned with ghosts as A Christmas Carol. Indeed, The Haunted Man, even more than A Christmas Carol a meditation on memory, may well be said to be itself particularly haunted by Dickens’s own first Christmas ghost story, already a familiar narrative to the English public. The fact that both were almost immediately converted to theatrical pieces reinforced this impression, because the physical demands of staging emphasized the similarities between the two tales. This was of course most apparent in the necessary centrality in the staging of either piece of the effect of the ghost, which will be a major concern of this chapter. Just as the later play is haunted in many ways by A Christmas Carol, its eponymous hero Redlaw is surely haunted in the minds of readers and viewers, by the figure of Scrooge, already by this time an iconic figure. Clearly Dickens has sought to emphasize this echo. Redlaw is another solitary, ageing, reclusive figure, with hollow cheek and sunken eye, a ‘black-attired figure, indefinably grim,’ his manner ‘taciturn, thoughtful, gloomy, shadowed by habitual reserve, retiring always and jocund never.’7 And finally, of course, Redlaw is visited by a ghost who ultimately brings him change and redemption.

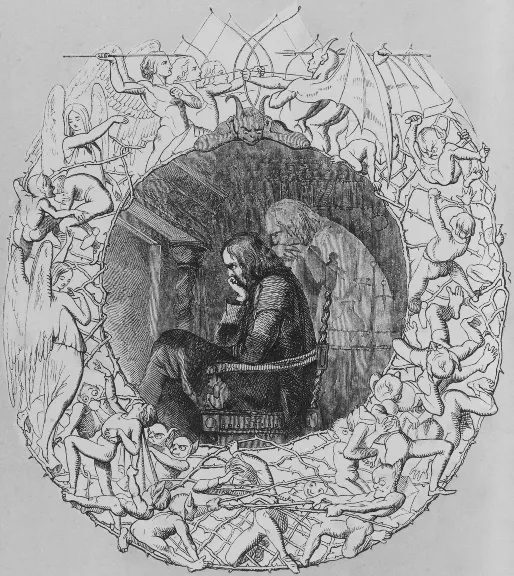

The frontispiece to the first edition by John Tenniel (Figure 1.1) immediately fixes Redlaw in the reader’s imagination, but although the image would perfectly suit the gloomy Scrooge of the opening pages of his story, especially in the unsettling moment when he seems to see Marley’s ghastly face in the doorknocker, the frontispiece of A Christmas Carol by John Leech, another regular illustrator of Dickens’s works, entitled ‘Mr. Fezziwig’s Ball,’ pictures a world almost totally opposed to that of Scrooge. If A Christmas Carol, like The Haunted Man, begins with a discussion of death and ghosts, and climaxes with the actual appearance of a warning spirit, Leech’s frontispiece depicts one of the most lively and joyful scenes in the story, the Christmas party at old Fezziwig’s, where the young Scrooge was apprenticed. Far from being a ghostly double of Scrooge, like Marley, old Fezziwig is depicted as Scrooge’s opposite – hearty, generous, full of the joy of life, and a model employer.

In contrast, in Tenniel’s frontispiece to The Haunted Man, Christmas is suggested not by healthy and exuberant festivity like the Fezziwig party, but by a dark and grotesque parody of a Christmas wreath, surrounding a gloomy picture of one of the darkest scenes in the story, Redlaw gazing gloomily into the fire, his ghostly double leaning over him and closely mirroring his despondent expression. The visual element that crowns this dark scene and ties it to the encircling wreath is a smiling demon, watching over the scene below and tied into it by a similar darkened colouring. The rest of the wreath, lighter in colour, shows a struggle reminiscent of a morality play between angels on the left and demons on the right, apparently over the souls of a number of naked human figures worked into the design. At this point it is clear that the demons are winning. Eight human souls are depicted, none of them under the protection of the angels, and several, like the central figure at the bottom, being actively tortured by the demons. To the left of Redlaw, a single human figure reaches out toward an angel, who extends no help to him while two grimacing demons hold him back. To further emphasize the dark message of this wreath, its background suggests a woven net of entrapment, composed of thorny briars, while its crowning elements, suggesting the flames of hell, and perhaps also of Redlaw’s hearth, take their shape from the bows of the demons and their pointed wings, not from the rounded wings of the angels.8

Figure 1.1 John Tenniel, Frontispiece to Charles Dickens, The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain: A Fancy for Christmas-Time (London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848)

Although Dickens stressed the ghostly element of A Christmas Carol in his prefatory remarks, the story actually began not with ghosts but with death, extending consideration of the word ‘dead’ and such sayings as ‘dead as a doornail’ through several paragraphs before beginning the actual story.9 The actual word ‘ghost’ does not appear in the first thirteen pages of the book, not until Scrooge identifies his frightening visitor as ‘Marley’s ghost.’ The Haunted Man is structurally almost identical, except the grounding word of the opening is not ‘dead’ but ‘ghost,’ even more distinctly foregrounded here than ‘dead’ was at the beginning of A Christmas Carol. It is worth quoting the exact words of the opening to see the striking way in which Dickens introduces his subject:

Everybody said so.

Far be it from me to assert that what everybody says must be true. Everybody is, often, as likely to be wrong as right. In the general experience, everybody has been wrong so often, and it has taken, in most instances, such a weary while to find out how wrong, that the authority is proved to be fallible. Everybody may sometimes be right; ‘but that’s no rule,’ as the ghost of Giles Scroggins says in the ballad.

The dread word, GHOST, recals [sic] me.

Everybody said he looked like a haunted man.10

It is a rather odd opening, much less directly tied, at least in its beginning sentences, to the concerns of the story than the opening of A Christmas Carol. The conflict between what is generally thought and reality is only very indirectly involved in the story, which primarily deals with an insight that anticipates Freud – that the repression of the memories of past sorrows and wrongs causes continual psychic damage, which can only be fully cured by recovering and coming to terms with these memories.

The bridge to the actual story opening is equally arbitrary, but it does place the idea of the ghost at the centre of the reader’s consciousness. Obviously Dickens could have found many quotations in literature or popular culture to reinforce the difference between truth and general opinion. Moreover, the introduction leads to an incorrect conclusion. ‘Everybody’ in this case is in fact right. Redlaw looks like a haunted man to everybody, and indeed he is a haunted man. The development of an assertion actually counter to the narrative seems to have been set up by Dickens primarily to introduce the quotation from the ghost ballad, which in turn ‘recals’ him to his real concern, which is with ghosts and haunting.

‘Giles Scroggins’ Ghost,’ although generally forgotten today, was a highly popular comic folk song in the early nineteenth century. It told of Giles, who died on his wedding day, and returned as a ghost in the dream of his fiancée Molly to ask her to join him in the grave. The key couplet runs:

Says She ‘I am not dead you fool’

Says the ghost, says he, ‘Vy, that’s no rule.’

It really seems that Dickens, focused upon the ghost as the key figure of his story, thought to lead into it by a reference to one of the most popular ghost ballads of the time, and in turn created an introduction that would lead to a quotation of the best-known line in that ballad.11 Thus, even more directly than A Christmas Carol, The Haunted Man characterized itself from the very outset as a ghost story, even if the ghost in the later work is of a very different type. Marley, in particular, and even the spirits he sends, may be considered as projections of Scrooge’s imagination, but they appear as separate, if ephemeral entities, like Giles Scroggins, or indeed the typical ghost. Marley is presented as very similar in his practices and values to Scrooge, but he is always seen as a parallel but separate figure, far from being Scrooge’s doppelgänger.

Redlaw is haunted by a different kind of ghost, as Tenniel’s frontispiece makes clear. The ghost is specifically a double of Redlaw, in a sense a consolidation of those memories he has refused to confront directly. The first appearance of this ghost emphasizes its ground as Redlaw’s double: ‘As the gloom and shadow ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Theatre and Spectrality

- Part I Ghosts, Stage Adaptation and Technology

- Part II Spectral Economies

- Part III Modernity, Gender and Ghost Aesthetics

- Part IV Acting, Absence and Rematerialization

- Select Bibliography

- Index