This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Works of theatre that depict grievous histories derive their force from making audible voices of the past. Such performances, theatrical or tourist, require the attentive belief of spectators. This engaging new study explores how theatricality works in each instance and how 'playing the part' of the listener can be understood in ethical terms.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Theatricality, Dark Tourism and Ethical Spectatorship by E. Willis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Performing Arts1

Landscapes of Aftermath

Tourism is an ideal metaphorical context for the messy collision of Self and Other in life […]. It is a practice in which self-gratification, self-exploration, and social engagement all take centre stage, often at the same time; hence we can use it as an exemplary context for thinking through questions about our relationships to ourselves and others and about the responsibilities we may hold on these fronts,

Kellee Caton, ‘Taking the Moral Turn in Tourism Studies’ 1921–2

Rather than a debased or trivial engagement, tourism names a performance of alterity. Tourism is one of the ways we make sense out of parts of the world not previously known to us, and of the experiences in our own world that are ‘inconceivable’.

Laurie Beth Clark, ‘Coming to Terms with Trauma Tourism’

The spectator is an actor.

Emmanuel Levinas, Basic Philosophical Writings 39

Whilst this is foremost a book about theatre and theatricality, it rests upon the consideration of a particular kind of tourist practice, which I characterize as ‘audience to absence’. Both theatre and dark tourism are haunted by absence and, each in their own manner, traffic in substitutes that attempt to make such absence present, to make it felt. This chapter explores a series of questions that lay down the terms of enquiry for subsequent chapters: What is dark tourism and what might motivate it? In what sense is it theatrical? How might we understand the various roles that tourists take on in relation to the sites discussed? What kinds of theatrical practices speak to the dialectic of absence and presence that this book seeks to read in ethical terms. As Kellee Caton’s comment above, drawn from her survey article, makes clear, an elaboration of what is at stake in the instances of tourism examined has ethical implications for the broader analysis of spectatorship at hand. Laurie Beth Clark, also quoted above, similarly suggests that tourism is one of the ways in which we attempt to approach and understand otherness. This chapter takes up the questions that dark tourism generates and considers them from an explicitly theatrical perspective. Theatricality, for this purpose, is understood as an animating force that traffics in paradoxes and contradiction: it calls into presence that which is absent, whilst at the same time always revealing the incompleteness of the invocation.

Dark tourism: a peculiar entertainment

To begin with I would like to define the field and its terms more fully than I did in the Introduction. The accessible and familiar nature of the examples discussed by Lennon and Foley in their millennial text, Dark Tourism, ranging from memorials to historical re-enactments, and including museums, Nazi death camps, and assassination sites, as well as the catchy descriptor – dark tourism – gave a recognizable name to a diverse and sociologically complex phenomenon. Subsequent analyses of ‘death and disaster’ attractions have included everything from the benign and kitsch – The Clink museum in London, ghost tours of haunted buildings, Prohibition-era gangster hot spots in Chicago; to the reverential – concentration camp memorials and sites of recent loss such as the 9/11 Memorial in New York; to the morally problematic – the Body Worlds exhibition and thrill-seeking war-zone tourism. Tony Seaton, in his explanation of what he calls ‘thanatourism’, offers five different categories of distinction: ‘travel to witness public enactments of death’ (240), ‘travel to see the sites of mass or individual deaths after they have occurred’ (241), ‘travel to internment sites of, and memorials to, the dead’, ‘travel to view the material evidence, or symbolic representations of death’ (242), and ‘travel for re-enactments or simulation of death’. Richard Sharpley rather more lyrically categorizes ‘divisions of the dark’ as: ‘perilous places’, ‘houses of horror’, ‘fields of fatality’, ‘tours of torment’ and ‘themed thanatos’ (11). The various examples given in this book focus largely on memorial sites that mark mass deaths, but also include elements of re-enactment and symbolic representation. I have employed the term ‘dark tourism’ because of the broad congregation of various types of spectator engagement that it gathers together.

Whether called dark tourism, deathly tourism, thanatourism (Seaton), the dissonant heritage of atrocity (Tunbirdge and Ashworth), tragic tourism (Lippard) or trauma tourism (Clark), the contemporary attractions of deathly spectacles and sites is usefully read, as Seaton contends in terms of a historical continuum. In an article for The Observer, Lennon, as cited in the previous chapter, writes: ‘The Battle of Waterloo in 1815 was observed by nobility from a safe distance and one of the earliest battlefields of the American Civil War (Manassas) was sold the next day as a visitor attraction site’ (qtd. in The Observer). One might go still further back in history to find precursors if not explicit examples of gruesome spectatorship, such as gladiatorial clashes, public executions and so on. Seaton suggests that such ‘thanatoptic presentations’ concerned with the ‘contemplation of death’ made death ‘a highly normal and present element in everyday life’ (237) and as such served as moral public (Christian) instruction. Significantly, as emphasized by his deployment of the term ‘presentations’, deathly spectacles from the ‘deadly charades’ of Roman naumachaie, massive re-enactments of naval battles in which captured prisoners played out their parts to the death (Kyle, 54), to the persistence of public executions in the millennia that followed, to the anatomical theatres of Stuart England, demonstrate an explicitly theatrical character. Indeed, Seaton makes particular note of the popular medieval Dance of Death tradition. In a study of late medieval and early modern theatrical depictions of dismembered bodies, Margaret Owens cites an alleged incident in sixteenth-century France, where a criminal’s execution was publicly staged within a performance of the biblical story of Judith (24). In a related example from the same historical period, Erika Fischer-Lichte describes a scenario where:

Spectators would crowd around the corpse after an execution in order to touch the deceased’s body, blood, limbs, or even lethal cord. They hoped that this physical contact would cure them of illness and generally provide a guarantee for their own bodily well-being and integrity.

(14–15)

Seeking out the dead, early modern spectators hoped that they might grasp something of the mysterious darkness, into which they had witnessed the formerly living disappear, and that this contact might have a transformative effect. These various historical precedents show a spectrum of motivations and contexts but also demonstrate a consistent theatricality across the range.

Seaton makes three important distinctions between these historical antecedents and contemporary thanatourism: movement from religious to secular contexts, a change of emphasis from the public and communal to the private and individual, and the development of tropes rooted in romanticism that associated pleasure with pain and death (237–8). The example of Waterloo acts as a curtain-raiser to contemporary dark tourism insofar as the proto-modern figure of the flâneur wandered onto the sidelines of an event that concerned him or her only as a peculiar entertainment and can be seen precisely as thanatoptic as argued by Seaton. Unlike the Roman naumachaie, which were explicitly staged as public performances, or executions that served a public, political and social function, front-row seats on the battlefield were not in any sense a necessary part of the event itself. If we are to think about contemporary dark tourism that might parallel Waterloo, then danger tourism, tourism through sites of natural or man-made catastrophe, and slum tourism (‘poorism’) provide examples. Such tourism can be understood as both marginal, in the sense meant by Elizabeth Burns when she writes: ‘The theatrical quality of life […] seems to be experienced most concretely by those who feel themselves on the margin of events […] because they have adopted the role of spectator’ (11), and at the same time highly immersive and affective. Tourists are plunged into the world of the other and at the same time derive pleasure from the experience precisely because of its alterity – the sense in which that world is not their own. Alex Garland provides an example of this in his novel, The Beach:

I wanted to witness extreme poverty. I saw it as a necessary experience for anyone who wanted to appear worldly and interesting. Of course witnessing poverty was the first to be ticked off the list. Then I had to graduate to the more obscure stuff. Being in a riot was something I pursued with a truly obsessive zeal, along with being tear-gassed and hearing gunshots fired in anger. Another list item was having a brush with my own death.

(163–4)

The emphasis in Garland’s text is not on acts of observation or witnessing that generate testimony and that might contribute to social change, but on the personal value to be extracted from standing on the sidelines of what Susan Sontag calls the ‘pain of others’ (Regarding the Pain of Others). The protagonist’s desire for affective experience also reflects what is discussed in tourism and business spheres as ‘the experience economy’, a term coined by Pine and Gilmour in their 1999 book of the same name. The example illustrates a collision of contemporary mobility, mediatization and the neoliberal political paradigm, where the spectacular gratification of the individual is placed at the centre of economic and social life. The scenarios described by Garland are at the extreme end of the dark tourism scale and are quite markedly different from reverentially framed experiences such as visiting former concentration camp sites. However, the critique that the more thrill-seeking types of dark tourism generate overlaps with the ethical issues that arise at memorials, such as Murambi in Rwanda, for example, which I do discuss, where preserved bodies of the dead are the main exhibit.

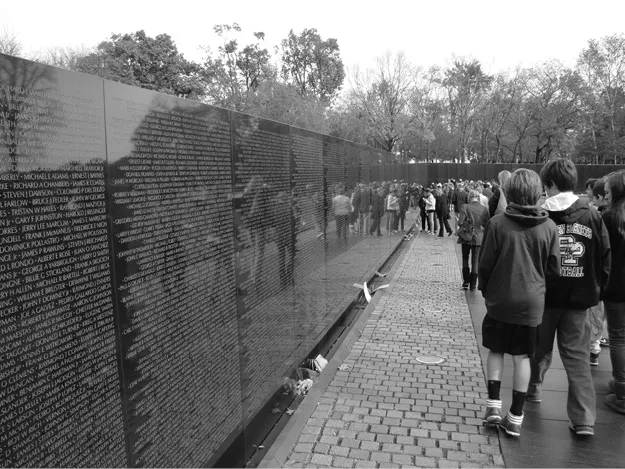

What characterizes most of the examples in this book, however, is precisely the other’s physical absence from the scene, and it is because of this defining absence, I suggest, that theatricality imbues the scenarios discussed. This is a different kind of dramatic scenario from the objectifying spectacles referred to above and one that relies on theatrical alterity rather than full-scale dramatic immersion. At such scenes, affect is generated by the lack (or missing) of an objectified other and as a means of making them ‘present’ in order that their suffering might be more fully contemplated. Whereas Garland’s protagonist wants to experience violence and suffering first hand, memorial sites in particular are often charged with absenting explicit violence from the remembering scene. When one visits the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC, for example, it is the names of the dead and only those names that are rendered visible (Figure 1.1). At Choeung Ek in Cambodia, violence is described rather than depicted (Figure 1.2). Because of their containment of violence, such memorials become spaces of contemplation where violence is either imagined rather than shown, or else deferred altogether.

The issue of motivation – why dark tourist attractions appeal – dominates much of the literature, particularly the work of Stone and Sharpley. If, as Seaton suggests, one of the principle motivations of tourism generally has been ‘a quest for The Other’, (238), then the question here is why the suffering other, whose depiction may in turn cause pain for the spectator? Clark gives a helpful qualification of the difficulty of the task:

Figure 1.1 Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington DC, 2012 (Photograph: Emma Willis)

Figure 1.2 ‘Killing Tree’, Choueng Ek, Cambodia, 2008 (Photograph: Emma Willis)

The range of visitors […] varies widely to include victims, survivors and their families; those who are politically or ethnically allied; students and scholars and intentional and accidental visitors. They bring with them a wide range of expectations, hopes, goals and needs, and an extraordinary variety of desires and behaviors. They may be seeking redemption, reconciliation, or revenge. They may come in solidarity with or in opposition to the professed politics of the site. They may be well prepared regarding the political and social history or they may be completely naïve.

The quest to draw conclusions as to visitor motivation is therefore challenged by the varied contexts from which spectators are drawn, which in turn affects the meaning that they gain from their experience. Lucy Lippard, similarly to Clark, notes: ‘We have no way of knowing what other people are feeling when they visit those redolent places. False reverence may be paraded; deep sadness may be hidden’ (119). Indeed, the desire to illuminate motivation stems from the very ambivalence and uneasiness that characterizes the enterprise, which may be interpreted equally as reverential acknowledgement or voyeuristic rubber-necking. It is important to acknowledge that for those working from within tourism, there is much motivation to explain the impulse for visiting dark tourist sites in constructive terms. Tunbridge and Ashworth, for example, in their discussion of ‘the heritage of atrocity’, explicitly focus on ‘the qualities of any atrocity that render it usable’ as a heritage site (104). They remark upon effective management strategies, noting the impact, for example, of: ‘the unusual or spectacular over the rather more commonplace’. They further identify guidelines for framing historical narratives: ‘victims should be characterized by innocence, vulnerability and non-complicity’, while perpetrators should be ‘unambiguously identifiable, preferably as a distinguishable group, different from the victims, and ideally also from the observer for whom the event is interpreted’ (104–5). It is difficult therefore for studies that focus on the management of dark tourism sites to ask questions such as that proposed by Lippard when she asks, does ‘tourism itself [have] any relevance to the depth of memory that monuments hope to induce’ (129)? Does the desire of heritage tourism to make visible and coherent the invisible and incomprehensible render it inadequate to the task of remembrance? The desire to explain the motivation for dark tourism is not easily disentangled from what is at stake in promoting its profile both publically and academically.

While this book does not primarily concern itself with visitor motivation, the pretext for the occasion of dark tourism is important to any attempted ethical reading of the interactions and experiences that take place at the various sites discussed. Therefore I would like to introduce two particular paradigms that help frame the terms by which dark tourism is commonly explicated: the ontological, which includes the contemplative, personal and even mystical; and the political, which is concerned with how such activity is understood in relation to narratives of power. These frames remain salient throughout the book and span the ethical analysis, serving to bring into contrast, for example, the perspectives on ethics of Levinas and Rancière. In their 2008 article, ‘Consuming Dark Tourism: A Thanatalogical Perspective’, Stone and Sharpley suggest, as noted in the previous chapter, that dark tourism is motivated by the sequestration and secularization of death in contemporary society and serves the human need to confront and contemplate themes of mortality. They offer a conceptual model that proposes a paradoxical interplay of presence and absence, which they suggest governs the relationship between individual, society and death in contemporary Western culture. Their model builds upon the arguments of Seaton, who writes that until the beginning of the twentieth century deathly presentations were much more normalized within everyday life. Stone and Sharpley suggest the withdrawal of ‘thanatoptic presentations’ therefore creates a lack, which dark tourism responds to and which marks it as a contemporary phenomenon. They characterize this lack as an erosion of former models of ontological security in relation to death – the decline of religion and so on – which in term leads to an over-emphasis of death in popular culture. The insecurity and dread generated by the decline of ontological security, they argue, motivates individuals to seek deathly experience out in order that they may gain insight from the encounter. Dark tourism therefore ‘allows individuals to (uncomfortably) indulge their curiosity and fascination with thanatological concerns in a socially acceptable and, indeed, often sanctioned environment, thus providing them with an opportunity to construct their own contemplations of mortality’ (Stone and Sharpley, 587).

Reading Stone and Sharpley’s work one cannot help but reflect on its Bataille-esque character, particularly in its configuration of the relationship between modernity, death and the sacred. In ‘The Practice of Joy Before Death’, Bataille attempts to articulate a mode of being or living, in which without literally giving way to death we confront it and in some way feel its force (Visions of Excess 235–7). Similarly, in the introduction to Death and Sensuality, he argues that it is only through a closeness to death that we can attempt to overcome the ‘discontinuous’ nature of our lives: ‘It is my intention to suggest that for us, discontinuous beings that we are, death means continuity of being’ (13). This practice is, as Benjamin Noys argues, essentially an aesthetic one, which uses substitution and imagination in order to cut through ‘day-to-day reality and leave the real exposed’ (103). Amy Hollywood further remarks:

For Bataille, inner experience begins with dramatization and meditation on ‘images of explosion and of being lacerated – ripped to pieces’ […] Meditation on the wounded body of the other lacerates the onlooker’s subjectivity; Bataille argues that ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes for the Traveller: Introduction to the Journey Ahead

- 1 Landscapes of Aftermath

- 2 Performing Museums and Memorial Bodies: Theatre in the Shadows of the Crematoria

- 3 Vietnam: ‘Not the bullshit story in the Lonely Planet’

- 4 ‘Here was the place’: (Re)Performing Khmer Rouge Archives of Violence

- 5 Lost in Our Own Land: Re-Enacting Colonial Violence

- 6 ‘The world watched’: Witnessing Genocide

- 7 Phantom Speak

- Works Cited

- Index