This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A global cast of contributors document the various forms of diaspora engagement – philanthropy, volunteerism, advocacy, entrepreneurship, and virtual diaspora - in South Asia and provide insights on how to tap the development potential of diaspora engagement for countries in South Asia.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Diaspora Engagement and Development in South Asia by T. Yong, M. Rahman, T. Yong,M. Rahman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economia & Politica economica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EconomiaSubtopic

Politica economica1

From Germany to India: The Role of NRIs and PIOs in Economic and Social Development Assistance

Pierre Gottschlich

Introduction

The Non-Resident Indian (NRI) and People of Indian Origin (PIO) population in Germany is one of the less prominent Indian diaspora communities. Despite its comparatively small size of only about 65,000–75,000 persons, this group plays a significant role in economic and social development assistance from Germany to India. It does so in many different ways. One of the most direct forms of economic support is the transfer of workers’ remittances. In 2010 alone, more than USD 500 million have been sent from Germany to India as remittances, which is particularly impressive given the relatively small size of the Indian population in the country. Another important way of economic engagement involves all sorts of foreign direct investments (FDI) and Indo-German business entrepreneurship in India. Here, the NRI and PIO population has helped in setting up some of the most central supporting organizations, particularly the Indo-German Chamber of Commerce (IGCC) which has been and continues to be of prime importance for the development of good business relations between India and Germany. A less formal, recently established business network is the German-Indian Round Table (GIRT). Another means of development assistance can be found in a plethora of German charity organizations that deal with economic and social challenges in India, mainly with regard to poverty alleviation. Many of these groups have been initiated by NRIs and PIOs who are also very active in the day-to-day work of these organizations both in Germany and in India. A case in point is the association ‘Indienhilfe’ (‘Help for India’). Additionally, grassroots translocal activities outside the network of charity groups, private donations and other forms of philanthropy do also play a major role. A third, more indirect way of diaspora engagement for India concerns activities in the realm of politics. Although a rather small population group, the Indo-German community has three Members of Parliament at a national level. These three and virtually all other PIO politicians in Germany are particularly devoted to good relations between the two countries. In doing so, they are not only committed to economic affairs but also foster cooperation programmes in the health, energy and education sector. Furthermore, lobby work can help secure official development assistance programmes and financial aid for India by the German government.

This chapter is designed as an empirical case study. It attempts to shed light on all the different forms of diaspora engagement from Germany to India mentioned above. It will start with a brief overall assessment of the NRI and PIO population in Germany, including its recent history and general profile. It will then proceed to analyze the many diverse ways of financial, economic, social, charitable and political contributions this specific diaspora group can offer for India.

Overview: The Indian diaspora in Germany

Although the history of Indian settlement in Germany dates back more than one hundred years, the modern Indian diaspora in Germany only came into being after the Second World War (Goel, 2007; Gottschlich, 2012a). In the 1950s, several thousand students from India came to Western Germany, that is, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), which was a result of the good diplomatic relations between the two countries. Most of these students were technicians and engineers who came from Indian universities or from Indian companies like, for instance, the steel mill in Rourkela, Orissa. They were granted scholarships for further education, and while many of them returned to India after their studies, some stayed and formed the nucleus of an Indian diaspora in Germany (Gosalia, 2002: 238). Most of the Indians who stayed were able to establish themselves in the German middle class. Due to their excellent education they usually worked in good jobs and were integrated very well (Goel, 2007: 358–359). In the late 1960s and early 1970s, close to 6,000 Indian nurses came to Germany in order to find work at hospitals. Interestingly, these ‘angels from India’ were mostly Catholic nurses from Kerala who were recruited through the global network of the Catholic Church (Goel, 2002: 61–63). This led to a huge disproportional share of Christian Indians in the diaspora in Germany, at least if compared to religion statistics in India (Schnepel, 2004: 117–118). Some of these nurses married Germans. Their children are an important part of the German-Indian population (Gosalia, 2002: 238). In all, the Indian community in Germany formed itself during that era as a community of professionals (e.g. nurses, doctors and engineers), academics (e.g. students, scholars and scientists), and businessmen and traders (Singhvi et al., 2001: 151–152). They mostly adapted to life in Germany and integrated themselves into the German society (Gosalia, 2002: 239). New impetus came in 2000 with the launch of the Green Card initiative by the German government, which brought a new wave of highly skilled Indian technicians, computer engineers and IT specialists to the country. This has so far been the last major influx of a specific immigrant group from India to Germany. However, Germany has recently become a more popular destination for Indian students and continues to attract Indian scholars and academics.

The Indian population in Germany is relatively small. According to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany, there were 48,280 Indian citizens living in Germany at the end of the year 2010. After a slight decline between 2003 and 2004, the number of NRIs in Germany, which had been around 35,000 for most of the 1990s, has been steadily growing since. The major reason for this growth has been the increasing immigration of Indians to Germany. In 2009, for example, 12,009 Indian citizens came to Germany while only 10,374 left the country, resulting in a net migration surplus of 1,635 persons. In 2008, the surplus was even higher at 1,871, with 11,403 coming and just 9,532 leaving (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2011: 249–251). Since 1991, there have been only two years (1994, 1998) in which the number of Indians leaving Germany was slightly higher than that of Indians coming to the country (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2011: 27–28, 249–251). For the overall picture, however, it is necessary to assess not only the number of NRIs but also the quantity of PIOs living in Germany. This is not always easy since there is hardly any specific statistical data on Indians after they have obtained German citizenship. According to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany, more than 8,000 Indians were naturalized and officially became German citizens between 2002 and 2010 alone. The children of PIOs are not a part of any official census, which makes it very difficult to measure the overall strength of the Indo-German community exactly. However, there have been some reliable calculations. In 2001, for instance, the High Level Committee on the Indian Diaspora estimated the number of PIOs in Germany at 10,000 (Singhvi et al., 2001: 152). Given the further inflow of Indian immigrants to Germany in the wake of the Green Card initiative and the ongoing processes of naturalization, it seems to be justified to hold this measurement as a mere minimum. In 2006, the number of PIO card holders in Germany was estimated at roughly 17,500. More current assessments have put the number of all PIOs as high as 25,000. According to data from the World Bank, the total migrant stock from India in Germany was 67,779 persons in 2010. Unfortunately, however, there is no definite measurement. Therefore, the overall number of NRIs and PIOs remains somewhat obscure: The Indian community in Germany numbers at least 65,000, probably 75,000, possibly even more than that.

The type of Indians migrating to Germany can be described overall as highly skilled labour. Data from the Federal Statistical Office of Germany show that except for the immigrants under family reunification regulations, highly skilled professionals comprise the largest group of NRIs living in Germany on a temporary residence permit, followed by Indian students. More than a third of all immigrants from India come into Germany explicitly for working purposes, most of them in the highly skilled sector. The level of education among Indian immigrants is relatively high. According to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany, migrants from South and Southeast Asia in general tend to be well educated, with approximately 40 per cent of them having at least completed some sort of secondary school and another 25 per cent still in education. What is more, the educational achievements of second- and third-generation PIOs in Germany tend to be even higher than those of their parents and grandparents (Gries, 2000). Not surprisingly, NRIs and PIOs in Germany are economically well established and for the most part employed in good positions. The percentage of low or semi-skilled workers is relatively low and the proportion of highly skilled or self-employed professionals is significantly higher compared to the occupational profile of other immigrant groups from South and Southeast Asia. Indians in Germany usually work in typical middle-class positions, for example as clerks, doctors, scientists or businessmen (Gries, 2000). Their average income is among the highest of all migrant groups, giving much room to contribute to the development of their home country in financial terms or in other forms.

Financial contributions: Remittances and NRI deposits

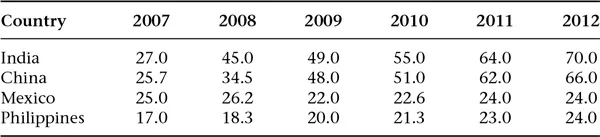

Besides direct expatriate investments, ‘inward remittances and non-resident deposits form the two main sources through which the overseas Indian community has been supplementing India’s resources and developmental efforts’ (Palit, 2009: 267). Particularly, remittances ‘directly contribute to the growth and development of the recipient country’ and often times even exceed the amount of overseas development assistance (ODA) and FDI a country receives (Kelegama, 2011: 3). Remittances can be of prime importance to the macroeconomic stability since they tend to be more sustainable, reliable and predictable than either ODA or FDI, especially after the economic crisis of 2008 (Agunias and Newland, 2012: 113, 125–126). In India, remittances have had and continue to have a positive effect on the balance of payments (BOP) although their relative share in India’s total foreign currency assets is declining despite a continuing rise in absolute numbers (see Table 1.1). Furthermore, remittances still are one of the main factors in limiting India’s current account deficit (CAD) (Palit, 2009: 270–271). Apart from this macroeconomic significance, remittances of course serve as an important lifeline for millions of families on an individual level (Agunias and Newland, 2012: 131).

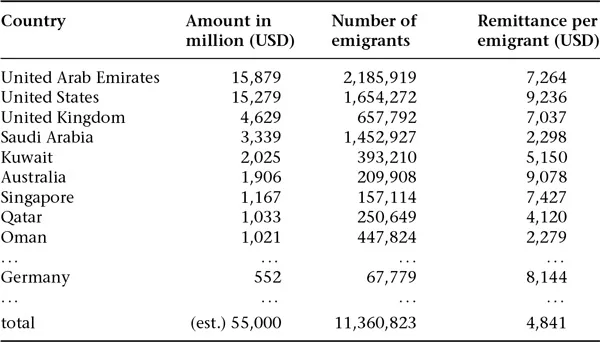

With their impressive educational record, their unique professional profile and their high household income, Indians in Germany fulfil every prerequisite for an important remittance-sending diaspora community. According to estimates by the World Bank, remittances in the volume of USD 511,711,400 have been sent from Germany to India in 2010. With this amount, Germany ranks not even near the countries with the highest total remittance to India such as the United Arab Emirates, the United States, the United Kingdom or Saudi Arabia (see Table 1.2). However, because of the comparatively small size of the Indian population in Germany, the amount of remittance per emigrant is relatively high at USD 8,144 a year and almost doubles the average yearly sum of USD 4,841.

Table 1.1 Top remittance-receiving countries (billion USD, est.)

Source: World Bank data; S. Irudaya Rajan, ‘India,’ in Migration, Remittances and Development in South Asia, edited by Saman Kelegama (New Delhi: Sage, 2011), p. 41; Dilip Ratha, Sanket Mohapatra and Ani Silwal, ‘Outlook for Remittance Flows 2010–11,’ Migration and Development Brief 12, April 23, 2010, p. 2; World Bank, Migration and Remittances Factbook 2011 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2011), p. 13; Dilip Ratha and Ani Silwal, ‘Remittance Flows in 2011: An Update,’ Migration and Development Brief 18, April 23, 2012, p. 2.

Table 1.2 Countries with highest total remittance to India (2010)

Source: World Bank data; Shafeeq Rahman, ‘Indians abroad are worth $55 billion,’ Tehelka, August 8, 2011, http://www.tehelka.com/story_main50.asp?filename=Ws080811Indians. asp, accessed October 13, 2011.

Another important part of the financial linkages between migrants from India and their homeland are NRI banking deposits. These specific deposits were first introduced in 1970 and have become very popular, particularly in the last decades, due to higher interest rates, relatively favourable tax treatment, comparatively easy operational conditions and steadily lowering transaction costs (Palit, 2009: 266, 276; Tumbe, 2012: 2). As one would expect, the United Kingdom with its large NRI population is unrivaled in Europe as far as the quantity of NRI deposits and the financial power is concerned. Germany, however, while being a distant second to the United Kingdom, outdoes all other European countries by a substantial margin (see Table 1.3). The UK accounts for approximately 70 per cent of all NRI deposits within the European Union, while Germany musters roughly 20 per cent, leaving only a mere 10 per cent for all other EU countries (Tumbe, 2012: 7). Hence, ‘it can be reasonably argued that outside of [the] UK, Germany is the most important source of capital flows, and perhaps remittances, from EU to India’ (Tumbe, 2012: 8).

In 2010, NRI deposits from Germany had a net worth of USD 1,550 million. Probably due to the economic and financial crisis, this number was lower than the sums for 2009 (USD 1,868 million) and even for 2008 (USD 1,633 million). Still, the sheer amount is very...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction: Diaspora Engagement and Development in South Asia

- 1. From Germany to India: The Role of NRIs and PIOs in Economic and Social Development Assistance

- 2. Influencing from Afar: Role of Pakistani Diaspora in Public Policy and Development in Pakistan

- 3. Afghan Diasporas in Britain and Germany: Dynamics, Engagements and Agency

- 4. The Global Circulation of Skill and Capital – Pathways of Return Migration of Indian Entrepreneurs from the United States to India

- 5. Bangladeshi Diaspora: Cultural Practices and Development Linkages

- 6. From Brain Drain to Brain Gain: Leveraging the Academic Diaspora for Development in Bangladesh

- 7. Diaspora Engagement in Education in Kerala, India

- 8. Diaspora Volunteering and Development in Nepal

- 9. Diasporic Shrines: Transnational Networks Linking South Asia through Pilgrimage and Welfare Development

- 10. Intersecting Diasporas: Sri Lankan Buddhist Temples in Malaysia and Development across the Indian Ocean

- 11. Diaspora Engagement Policy in South Asia

- 12. Pockets of the West: The Engagement of the Virtual Diaspora in India

- Index