![]()

C H A P T E R 1

Introduction: Getting Development Right

Eva Paus*

The celebratory tone about the emergence of the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, China) and the improved growth in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America during the 2000s obscures the reality that, for large parts of the developing world, the challenges of development are more acute than ever. After three decades of Washington Consensus policies, deepening globalization, and China’s and India’s rapid growth and increasing international competitiveness in ever more goods and services, many latecomers face three critical challenges: structural transformation, inclusion, and environmental sustainability.

This book brings together prominent scholars and practitioners from around the world who look beyond the current global crisis and short-term growth opportunities and take a long-term perspective in the analysis of inclusion, environmental sustainability, and structural transformation. The book deliberately includes an analysis of all three challenges to explore the relations among them in the articulation of a new development strategy. When we approach each challenge separately, we obfuscate possible trade-offs with the other challenges and miss the opportunity to devise policies that can minimize the tensions between the goals and maximize win-win outcomes. Our intention is to initiate an exploration of a more integrative policy response, cognizant of the complexity and contingency of the interrelations among these challenges. The chapters in this book, taken together, suggest several important policy areas where we might achieve a double or even triple dividend. But they also show that the adoption and implementation of such policies depends critically on the political will to change current rules and behavior and to translate loft rhetoric into hard-nosed action.

After nearly 200 years of divergence, “Divergence Big Time” (Pritchett 1997), many developing countries have seen some income convergence with the countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) during the 2000s. But it is unlikely that this trend can be sustained. What the basis for growth is matters. Informed by structuralist thinking (Ocampo et al. 2009), we argue that growth can only be sustained if it is based on a change in the structure of production toward higher-productivity activities. Starting in the 1980s, most countries in Latin America and Africa embraced the free market policies of the Washington Consensus which focused on efficiency and static comparative advantages and paid little attention to the importance of structural change for sustained growth. The result has been productivity-reducing structural change (Rodrik, this volume), where labor has moved to activities with lower, not higher, productivity. Productivity-enhancing structural change generates more decent jobs, while productivity-reducing structural change fosters the expansion of low-paid jobs and informality.

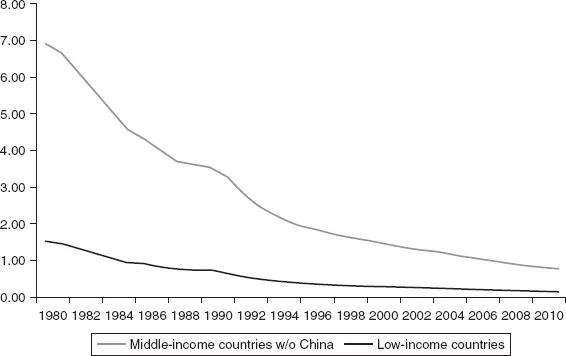

Furthermore, China (and a few other developing countries in Asia) did not follow Washington Consensus policies and fared rather differently. A very successful process of structural transformation has undergirded three decades of high economic growth in China. China’s impressive performance has meant that both low- and middle-income countries have seen a dramatic increase in income divergence with China (see figure 1.1). China’s ability to compete in low- as well as high-tech products has increased the urgency for other middle-income countries to focus their strategy on promoting structural change toward higher value-added activities.

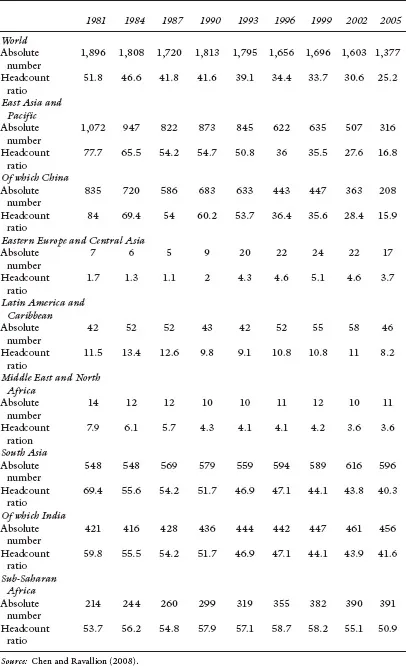

Inclusion is a broad concept with economic, political, and social dimensions. Here we focus primarily on reductions in poverty and inequality. The general trend over the past 20–30 years has been a decline in extreme poverty rates and an increase in inequality. One of the great achievements of the last decades has been a significant decrease in the rate of extreme poverty. The percentage of people living on less than $1.25 a day (2005 PPP) fell from 51.8 percent in 1981 to 25.2 percent in 2005. The global average conceals important regional differences. While the extreme poverty rate in China decreased from 84 to 16 percent, Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia saw a much smaller decline, and the two regions now account for the vast majority of the extreme poor (see table 1.1). The United Nations (2012:7) predicts that, in 2015, 1 billion people will still be living in extreme poverty, with 80 percent in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 1.1 GDP p.c. in country groupings relative to GDP p.c. in China (based on constant 2005 PPP).

Table 1.1 Number (in millions) and percentage of people living below $1.25 a day (2005 PPP)

Inequality offers a rather different picture from the trends in extreme poverty. We already noted what happened to intercountry inequality, which is captured by income divergence and convergence. The two most important exceptions to the continued increase in inequality among rich and poor countries are China and India. A telling indicator of global intercountry inequality is the ratio of the average income of the richest country to that of the poorest country. In 1820, that ratio was 3:1. Today it is 100:1 (Milanovic 2011:100)! Intracountry inequality has been on the rise over the last two decades, in developing and developed countries alike (Milanovic 2011).1 A notable exception is Latin America. Historically, this region has been one of the most unequal in the world, but in the 2000s inequality in Latin America declined (Cornia 2012, López-Calva and Lustig 2010).

The growing threats to environmental sustainability have many different dimensions, from deteriorating water and air quality to the increasing conversion of forests and wetlands to cultivated land, to rising global temperatures. The focus on environmental sustainability adds another critical dimension to inequality: intergenerational inequality. It was the Brundtland Report in 1987 that first urged us to aim for “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

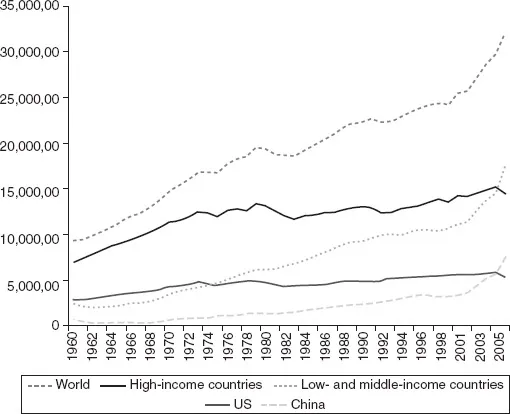

Emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), the major driver of global warming, have been growing unabatedly since 1960, with growth accelerating during the 2000s (see figure 1.2). Until the beginning of the industrialization process in the early 1800s, the atmosphere contained about 275 ppm (parts per million) of CO2. Today, the number is 392!2 A global grassroots movement to solve the climate crisis, 350.org, argues that 350 ppm is the safe level of CO2 in the atmosphere, if we want to avoid disastrous and irreversible climate impacts. The 4th Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2007) set the limit at 450 ppm to keep the global temperature rise to 2–2.4 percent, widely seen as the point beyond which major irreversible damage will occur.

Whatever the exact number for the tipping point, it is clear that there is urgency to slow the increase in CO2 levels and then reduce them.3 While today’s industrialized countries bear the main responsibility for the increase in CO2 in the atmosphere for most of the last two centuries, the rise in CO2 emissions over the last 30 years has increasingly been driven by developing countries. In 2009, high-income OECD countries accounted for about 36 percent of CO2 emissions, down from 60 percent in 1960. Over this period, China’s share in global emissions increased from 8.3 percent to 24 percent. China’s share for the latter year is roughly the same as that for all low- and middle-income countries combined, excluding China and India.

Figure 1.2 CO2 emissions (kt).

Source: Based on World Development Indicators.

The principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities,” established in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992, captures the need and capacity of industrialized countries to take the lead against climate change.4 Martin Khor (2010:65) translates the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” for the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions into a three-pronged approach:

Developing countries cannot afford to ignore the triple challenge of environmental sustainability, inclusion, and structural transformation. If they do not pay sufficient attention to the consequences of growth for the environment, the inevitable increase in CO2 emissions will affect people everywhere, but particularly and most immediately those who are most vulnerable. Increasing ecological scarcity and climate change have a disproportionate impact on the world’s poor, most of whom live in agricultural and remote areas in developing countries. So it is highly questionable that growth without regard to environmental consequences will benefit the poor in the future (Barbier and Markandya 2013).

If developing countries continue to follow Washington Consensus policies, it will probably mean a continuation of the centuries-old trend of divergence between rich and poor countries, as productivity-reducing structural change is likely to continue. In addition, the growing divergence between most developing countries and China (and increasingly India), due to the underlying divergence in production patterns, will make it ever more probable that declining wages, rather than increasing productivity, will become the basis for international competitiveness in the countries lagging behind (Paus 2012).

The contributors to this book offer many general and specific policy suggestions to address the challenges of structural transformation, inclusion, and environmental sustainability. Several recommendations are likely to render double and even triple dividends: A shift in policy focus to promoting structural change can engender productivity-based growth and convergence. That, in turn, would pave the way for the creation of more decent jobs and greater intracountry equality.5 The adoption, and eventual domestic development, of technology for a green economy can be the driver of structural change while also increasing environmental sustainability and thus intergenerational equality. The right management of natural resources can generate rents for structural transformation as well as contribute to environmental sustainability and poverty reduction. And social policies can support structural change as well as reduce intracountry inequality.

Each of the three sections in this book focuses primarily on one of the three challenges: structural transformation, inclusion, and environmental sustainability. In the remainder of this introduction, I summarize the main arguments and policy recommendations of the three sections highlighting the prospects for multiple dividends where possible. I conclude with a brief exploration of the challenges for policy implementation.

STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATION

There are many reasons why developing countries might grow for a certain period, for example, a commodity price boom, a construction boom, or an influx of remittances. But growth can only be sustained if it is based on broad-based upgrading where production is shifted increasingly toward activities with greater technological spillovers, increasing returns, and higher demand elasticities, within and across sectors. The underlying assumption of this structuralist view is that different activities have different potential to generate dynamic benefits (Ocampo et al. 2009). Empirical evidence shows that developing countries with a larger share of their activities in higher-value activities experience higher growth (Hausmann et al. 2007, Ocampo and Vos 2008:33–57).

Structural change was the rationale behind import substituting industrialization (ISI). Though policy implementation was often beset with problems, it is important to separate the legitimacy of the rationale from the deficiencies in implementation (Paus 2011). With the rise of the Washington Consensus in the 1980s, the focus of the dominant paradigm shifted from the creation of dynamic comparative advantages to static comparative advantages, short-term efficiencies, and macro stabilization. Trade liberalization, an open-arms approach to foreign direct investment and a retrenchment of the government’s role in production and sectoral development has led to deindustrialization and large informal sectors in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa.

The contributors in part I of this book (Rodrik, Cimoli et al., and Mkandawire) concur that the right kind of structural change is key for sustained growth and for lowering the intercountry inequality between latecomers and industrialized countries. In the current age of globalization, not only manufacturing b...