eBook - ePub

Borderlands in World History, 1700-1914

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Borderlands in World History, 1700-1914

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Covering two hundred years, this groundbreaking book brings together essays on borderlands by leading experts in the modern history of the Americas, Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia to offer the first historical study of borderlands with a global reach.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Borderlands in World History, 1700-1914 by P. Readman, C. Radding, C. Bryant, P. Readman,C. Radding,C. Bryant in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Writing Borderlands

1

Negotiating North America’s New National Borders

Benjamin H. Johnson

The introductory essay of this volume refers to the ‘diluvial proportions’ of the literature on borders and borderlands in North American history, a description that might with equal justice be applied to the entire historiography of the United States and the imperial currents from which it emerged in the late eighteenth century. Like US historiography as a whole, the body of work on North American borderlands simultaneously benefits and suffers from its richness and size: its students have the privilege of joining a scintillating and vibrant conversation, but at the same time its volume can all too easily crowd out the discussions emanating from other rooms in the mansion of history. Borderlands, as the introduction also notes, ‘were worldwide phenomena during the modern era,’ yet North Americanists have rooted their accounts in the distinctive regional, colonial, and national histories most clearly shaping their subjects.1 We have thereby left largely unexplored the question of whether or not there are important enough dynamics of borders and borderlands in general to warrant the kind of broadly comparative approach undertaken in this book, and locked ourselves in too close a conversation to learn from those examining similar developments elsewhere.

To historians interested in borders and borderlands, the replacement of empires by nation-states might appear as the key turning point in the history of North America, for nations seem invested in their boundaries in ways that empires are not. Jeremy Adelman and Stephen Aron emphasize just this viewpoint. They argue that in places where European empires competed for control—the Great Lakes, the Mississippi Valley, and Spanish Texas and New Mexico—native peoples often maintained broad autonomy and power. But in the nineteenth century, when European powers gave way to the nation-states of Canada, the United States, and Mexico, natives ended up as conquered peoples forced to live in the context of national, not borderland, societies. ‘Hereafter,’ they write, ‘the states of North America enjoyed unrivaled authority to confer or deny rights to peoples within their borders.’ These new borders divided North American peoples in new ways, but also had ramifications ‘for internal membership in the political communities of North America.’ ‘The rights of citizens—never apportioned equally—were now allocated by the force of law monopolized by ever more consolidated and centralized public authority.’ ‘With the consolidation of the state form of political communities,’ they conclude, ‘borderland peoples began the long political sojourn of survival within unrivaled polities.’2

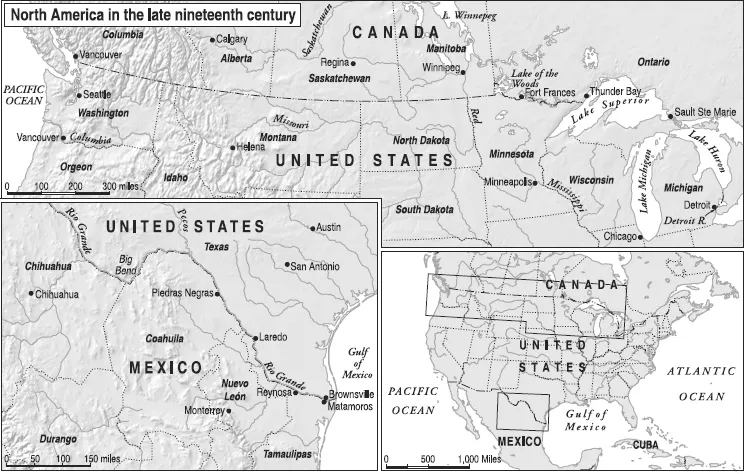

Map 1.1 North America in the late nineteenth century

Adelman and Aron were criticized, sometimes harshly, for downplaying the power of native peoples, for minimizing the ways in which nation-states were continuations of colonial processes rather than breaks from them, and for assuming that nations were more powerful than they were in actuality.3 Yet whatever the inadequacies of their depiction of different North American regions, the focus on the territorial ambitions of nation-states raises productive questions for scholars examining North America and suggests some ways to relate North American history to global history. Indeed, scholars of empire more generally point to the importance of similar shifts as those noted by Adelman and Aron. ‘Imperial and national frontiers,’ notes Charles Maier,

usually enclose different processes of governance and institutional structuration within their respective territories. The nation-state will strive for a homogenous territory. It imposes taxation, not equally on all classes, but more equally than an empire on all districts … eventually it strives for internal improvements and developments. Because of their size, and their assumption of power over old states and communities, empires possess a far less administratively uniform territory. They accommodate enclaves with local liberties and charters.4

Other scholarship points to a similarly more exclusive concept of territory, but links it less to the shift from empire to nation than to the rise of agrarian and industrial capitalism, which thrived in bounded (if linked) national economies where states guaranteed property rights and created accessible national markets. The most dynamic polities of the nineteenth century envisioned territory ‘not just as an acquisition or as a security buffer but as a decisive means of power and rule.’5

In the case of liberal Republics such as the United States, Mexico, and ultimately Canada, territory was particularly tightly bound up with the question of sovereignty and national identity. As President Abraham Lincoln told his Congress in 1862,

A nation may be said to consist of its territory, its people, and its laws. The territory is the only part which is of certain durability. ‘One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh, but the earth abideth forever.’ That portion of the earth’s surface which is owned and inhabited by the people of the United States is well adapted to be the home of one national family, and it is not well adapted for two, or more. Its vast extent, and its variety of climate and productions, are of advantage … for one people, whatever they might have been in former ages.6

This chapter uses the early history of the international borders that divided and linked Mexico, the United States, and Canada to argue that focusing on state power and its limits in this period would let North Americanists write accounts of these places that simultaneously reflect their historical specificity and are more open to comparison with similarities elsewhere. Specifically, it examines efforts to map the newly drawn borders and to police them against other claims to sovereignty mounted by native groups and border leaders. The unevenness and paradoxes of the state-building and territorial consolidation that redrew the continent’s map in the mid-nineteenth century not only make it helpful for historians to compare the two international borders to one another (rarely enough done), but also to make their studies part of a worldwide conversation about borderlands and borders.7

Modern maps tell us that borders are international spaces—zones made by the encounter of empires and nation-states. And yet even with the most powerful nation-states, they remained in critical ways contested, open, and permeable, to the frustration of metropolitan dreams of discrete sovereign spaces. In North America as elsewhere, non-national geographies, economies, and identities persisted into the twentieth century, and in some ways up to our own time. This tension is perhaps the great central theme of modern borderlands history.

On the Ground

The modern map of North America took shape with the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo between Mexico and the United States and the extension of the US–Canada border from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific along the 49th parallel after American saber-rattling. But maps are abstractions, and the first efforts to accurately survey the borders suggested just how weak was the grasp of central governments.

The joint US–Mexico survey provided for in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was to begin near the Spanish Mission at San Diego, California. But because the land route across the continent was so grueling and dangerous, the US party instead traveled by boat to Panama, crossed the narrow land bridge there, and sailed to California. The journey to Central America was uneventful, but once the US commissioners arrived there in March 1849, the flood of traffic prompted by the California gold rush delayed them for two full months, exhausting much of their funding in the process. Quarreling over finances was joined by a deeper split within the US side of the commission, with the northerners suspicious that southerners were intent on finding a southwestern route for a transcontinental railroad, and thus ensuring the spread of slavery westward. When the principal commissioners left the surveyors near the Gila River in Arizona for what was supposed to be a short resupply trip to Sonora, they became lost, spent several weeks in the desert, and became gravely ill. Pedro García Conde, the Mexican commissioner, died, while his US counterpart spent several months recuperating.8

It was not until four years later, in the summer of 1853, that mapping of the Rio Grande section of the border even began. Even this was hard to pull off: Yellow Fever killed the party’s doctor—and nearly one of the US head commissioners—while they awaited transport in Florida. Hurricanes turned the journey across the Gulf of Mexico, which usually took five days, into an eighteen-day ordeal. Once on land, the party depended on the protection of the US Army from the Apache, Comanche, and other Indian peoples who seemed not to know or care that their lands were now split between the United States and Mexico. Some of the river proved simply impossible to survey. The rugged terrain of the Big Bend country struck William Emory with its desolate beauty. ‘No description,’ he wrote, ‘can give an idea of the grandeur of the scenery through these mountains. There is no verdure to soften the bare and rugged view; no overhanging trees or green bushes to vary the scene from one of perfect desolation.’ The qualities that made the area visually striking precluded its adequate mapping, however. ‘Rocks are here piled one above another,’ continued Emory,

over which it was with the greatest labor that we could work our way. The long detours necessarily made to gain but a short distance for the pack-train on the river were rapidly exhausting the strength of the animals, and the spirit of the whole party began to flag. The loss of the boats, with provisions and clothing, had reduced the men to the shortest rations, and their scanty wardrobes scarcely afforded enough covering for decency. The sharp rocks of the mountains had cut the shoes from their feet, and blood, in many instances, marked their progress through the day’s work.

In the face of such hardship, the Commission headed south deep into Mexico, leaving this stretch of the border unsurveyed.9

Similar challenges confronted the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom as they parsed out the northern border. The 1846 treaty between Britain and the United States ended conflict—and perhaps avoided a war—by setting the 49th parallel as the land border between the Pacific and the Rocky Mountains. (In 1818 they had agreed on the 49th parallel as the border from Lake of the Woods to the Rockies.10) The 1856 Fraser River gold rush prompted colonial authorities to propose a joint survey of the still-unmarked line separating Washington Territory and British Columbia. Like their counterparts to the south, the difficulties of a land crossing required the surveying parties to travel across Panama and head up the Pacific coast by ship, a journey of some three months.11 The survey of the border between the ocean and the Rockies was completed in 1861. Again conditions on the ground hampered the work and suggested the limits of state power. The governor of British Columbia repeatedly requisitioned the British surveying party to keep the civil peace in his raucous gold-rush territory.12 ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Borderlands in a Global Perspective

- Part I Writing Borderlands

- Part II Borderlands, Territoriality, and Landscape

- Part III Borderlands and State Action

- Part IV National Identities and European Borderlands

- Part V Labor and Social Experience

- Part VI Reading Borders: Individuals and Their Borderlands

- Concluding Reflections: Borderlands History and the Categories of Historical Analysis

- Select Bibliography

- Index