This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

China's Outward Foreign Direct Investments and Impact on the World Economy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book studies the impact of China's outward foreign direct investment on the world economy. It uses both case studies and modeling approaches to study how China's investments have affected the rest of the world.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access China's Outward Foreign Direct Investments and Impact on the World Economy by Pan Wang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Comercio y aranceles. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

1 Background

China has achieved great economic success since the launch of the ‘Open Door’ policy in 1979. Up to 2009, China’s annual average growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP) was 9.9 per cent, which is around four times as much as the comparable figures for the rest of the world (2.9 per cent), the US (2.7 per cent), the UK (2.1 per cent) and Japan (2.3 per cent).1 China surpassed Japan as the second largest economy in 2010, even though Goldman Sachs (2003) predicted that this would occur no earlier than 2016. To quote Bloomberg:

The country of 1.3 billion people will overtake the U.S., where annual GDP is about $14 trillion, as the world’s largest economy by 2027, according to Goldman Sachs Group Inc. chief economist Jim O’Neill ... China overtook the U.S. last year as the biggest automobile market and Germany as the largest exporter. The nation is the world’s No. 1 buyer of iron ore and copper and the second-biggest importer of crude oil, and has underpinned demand for exports by its Asian neighbors. (Bloomberg, 16 August 2010)

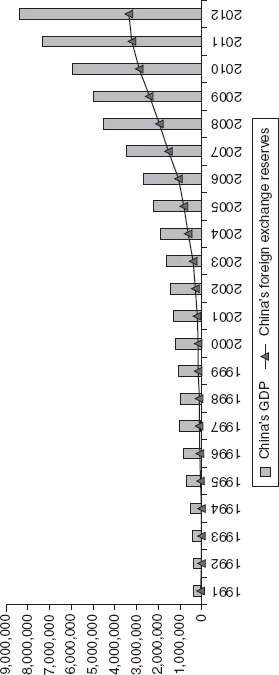

China’s foreign exchange reserves have increased rapidly alongside its fast economic growth and expanding trade surplus. They grew from a very limited scale in the early period of economic reform, to $2.5 trillion by 2009 and $3.4 trillion by 2013. China now has the largest foreign exchange reserves in the world, accounting for one-third of the global total and three times as large as that of Japan, the world’s second largest holder of foreign exchange reserves (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Values of China’s GDP and foreign exchange reserves (US$, million)

Source: World Bank’s World Development Indicator (various issues).

China’s fast economic growth has been accompanied by increasing consumption of natural resources, especially oil, ores and metals. However, China’s local production of these resources lags far behind demand. China’s dependency on oil imports has risen rapidly in recent years due to increasing demand and stagnant domestic production of oil (Figure 1.2).

Given the relatively stable production of oil, China’s oil consumption and imports have continuously increased, while, in contrast, the oil self-sufficiency rate has continuously declined.2

China’s rapid economic development has not only increased the demand for natural resources, but also raised the demand for advanced technology. It is anticipated that advanced technology will enhance economic growth. Consequently, China has actively established overseas R&D centres in developed countries, as well as directly acquiring foreign technologies. Furthermore, thirty years of economic growth has improved China’s own technology level and innovation capability, enabling it to exploit and transfer the technology that is embedded into its overseas investments.

Figure 1.2 China’s oil production, consumption, imports and self-sufficiency

Notes: Volumes of oil imports, domestic oil production and consumption (Left Axis). Oil self-sufficiency rate (Right Axis).

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, China Statistical Yearbook (various issues).

Investments in developing countries are usually accompanied by China’s own technology, which can often be superior to host country technology. The OECD (2008) analyses China’s investments in Africa, and recommends that African countries utilise China’s technology which is suitable for their local development.

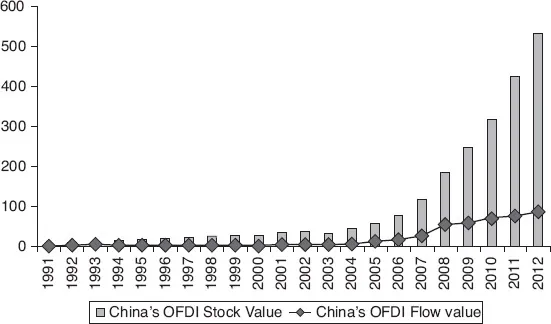

China’s fast economic growth, increasing domestic demand for energy and technology, as well as its accumulating foreign exchange reserves, all play a significant role in China’s recent surge in overseas investments. During 2003–09, the annual average growth rate of China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) was 71 per cent, while the world average OFDI expanded at around a quarter of China’s rate.3 MOC (2009) illustrates China’s recent surge in OFDI, indicating particularly that China outperformed many other countries in the post-crisis period. China ranked as the largest OFDI source country among the developing countries and the fifth largest source country in the world in 2009.

UNCTAD (2010a) reports that China will be the second most promising OFDI source country, after the US, in the next three years. The development of China’s OFDI is illustrated in Figure 1.3, which presents its flow value and stock value during 1991–2009.

Figure 1.3 Value of China’s OFDI flow and stock (US$, billion)

Source: Data for 1991–2002 are obtained from UNCTAD, World Investment Report (various issues) Data for 2003–12 are obtained from MOC (2011, 2012), Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment.

China’s OFDI reforms are closely related to its overall economic reforms. The ‘Open Door’ policy, launched in 1979, was the first policy to provide an institutional framework within which to implement OFDI. At this primary stage, China’s OFDI was mainly motivated by political rather than economic incentives (Cheung and Qian, 2009). And it was also the first reform for China’s overseas investments to encourage a more transparent and decentralised approval regime (Voss et al., 2009). OFDI activities were promoted by both central and local governments after Deng Xiaoping’s ‘South Tour’ in 1992. The launch of the ‘Go Global’ policy in 2002 and China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) boosted overseas investments. The OFDI policy was further liberalised from an approval regime to a supervision and assistance regime by the Ministry of Commerce (MOC).4 To quote The Economist:

Beijing will use its foreign exchange reserves, the largest in the world, to support and accelerate overseas expansion and acquisitions by Chinese companies, Wen Jiabao, the country’s premier, said in comments published on Tuesday. ‘We should hasten the implementation of our “going out” strategy and combine the utilisation of foreign exchange reserves with the “going out” of our enterprises,’ he told Chinese diplomats late on Monday. ... Qu Hongbin, chief China economist at HSBC, said: ‘This is the first time we have heard an official articulation of this policy ... to directly support corporations to buy offshore assets.’ (The Economist, 21 July 2009)

Yao and Sutherland (2009), Yao et al. (2010) and Xiao and Sun (2005) have pointed out that a distinctive feature of this recent surge has been the Chinese government’s use of substantially subsidised state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to implement the national strategic interest, such as securing a long-term supply of natural resources. China’s OFDI is clearly on a fast track to becoming a crucial driving force for the sustainable growth of the Chinese and global economy. However, there are growing debates about this surge. For some, China’s overseas investments have been interpreted as a threat rather than an opportunity. The Economist (2008), for instance, has claimed that Chinese investments are undermining the West’s existing interests, and that China is stealing natural resources and colonising Africa.

2 Motivations and objectives

This book studies the causes and consequences of China’s OFDI explosion by examining three broad subjects: (a) its underlying motivations and locational determinants; (b) the dynamic adjustment of China’s OFDI and its relationship with China’s inward foreign direct investment (IFDI); and (c) the impact of China’s OFDI on other source countries’ OFDI in the third-party host countries.

2.1 Locational determinants of China’s OFDI

Many characteristics of host countries have the potential to affect China’s OFDI, with natural resources and technology being among the most important factors.

Firstly, natural resources play a very important role in China’s overseas investments because China’s economy increasingly depends on the supply of foreign natural resources. For example, the continuously decreasing oil sufficiency rate, shown in Figure 1.2, has turned China from a net oil exporter to the second largest oil importer in the world. An early failed buyout of the California-based oil company Unocal and a recent failed buyout of Rio Tinto reflect China’s desire for natural resources. Ye (1992), Zhan (1995) and Taylor (2007) have pointed out that China’s overseas investments have sought to secure supplies of various natural resources. Existing empirical studies on the effect of natural resources on Chinese OFDI have produced mixed results; whereas some studies support a positive and significant association between Chinese OFDI and natural resources (Buckley et al., 2007; Cheung and Qian, 2009), other studies have found that the effect of a host country’s natural resources on China’s OFDI is insignificant (Zhang, 2009; Kolstad and Wiig, 2009).

Secondly, the host country’s technology may also be a key determinant of China’s overseas investments. The acquisition of the IBM PC business; the take-over of Volvo by Geely, one of the largest private auto makers in China; and the establishment of an R&D centre in the Nottingham Science Park by Chang An Auto, one of the four largest state-owned auto makers in China, imply that China is interested in acquiring advanced technology in developed countries. Child and Rodrigues (2005) and Mock et al. (2008) argue that the search for advanced technology, brands and management skills is an important motivation for China’s overseas investments. On the other hand, although China is still a developing country, thirty years of economic development have significantly improved China’s technology level.5 China’s technology is being utilised in developing countries, and the establishment of a motorcycle affiliate in Vietnam and a fridge affiliate in Nigeria imply that China may also be capable of exploiting and transferring its technology to developing countries. The dual role of technology on China’s overseas investment has yet to be systematically investigated.

The first empirical study of the book (Chapter 3) aims to examine the underlying motivations and locational determinants of China’s OFDI for 2003–09 and 1991–2003 respectively, with a particular focus on the role of natural resources and technology. The chapter aims to explain whether China’s OFDI is driven by an abundance of natural resources in the host country in accordance with a resources-seeking motivation, and how China’s OFDI responds to the technology level of the host country under the technology-seeking motivation and the technology-exploiting motivation. The chapter also explores how these motivations and effects vary across different time periods.

In terms of the natural resources-seeking motivation, this study sheds light on whether China’s OFDI is driven by different types of natural resources and whether China’s OFDI distinguishes them among overall resources, such as oil and metal. Furthermore, the chapter examines whether or not China’s OFDI is driven toward resource abundant countries with poor governance, as well as how China responds to booming mineral prices.

2.2 Dynamic adjustment of China’s OFDI and its relation with China’s IFDI

In addition to studying the determinants of China’s OFDI in a static framework, this book further examines the partial adjustment of China’s OFDI and its relationship with China’s IFDI in a dynamic framework.

To study the partial adjustment of China’s OFDI, the chapter adopts a methodology developed by Cheng and Kwan (2000) who introduced a partial stock adjustment model to examine the partial adjustment of FDI in a dynamic framework. This partial stock adjustment model indicates that the adjustment from the actual stock towards the equilibrium stock is gradual rather than instantaneous. The investment inertia takes time to adjust, and hence the adjustment cost smoothes the adjustment process. China’s OFDI might also face this dynamic adjustment and adjustment cost, although this has largely been ignored in previous studies.

For example, it is very time consuming for the government to approve a new investment project. Hence, there might be a significant time lag between the decision to invest and the actual implementation of the project.

Furthermore, China has only become a large FDI source country very recently, but it has long been acknowledged as an important FDI recipient. UNCTAD (2007) reports that China has been the top IFDI host country among developing countries since the late 1990s and one of the three largest FDI host countries in the world since 2005. The huge amount of IFDI stock not only provides essential capital but also strengthens China’s economic connection with the rest of the world. It is therefore reasonable to expect that China’s IFDI migh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Literature on China’s OFDI

- 3 China’s OFDI and Resource-seeking Strategy: A Case Study on Chinalco and Rio-Tinto

- 4 OFDI and Technology-seeking Strategy: A Case Study of Geely’s Acquisition of Volvo

- 5 Location, Resources and Technology of China’s OFDI

- 6 Dynamic Relationship between China’s IFDI and OFDI

- 7 Does China’s OFDI Displace OECD’s OFDI?

- 8 Policy Implications and Conclusions

- Appendices

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index