This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Intelligent Investing in Irrational Markets

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

As a game of economics, investing involves the basic principles of economics that help investors identify financial goals and constraints, and come up with the right asset and portfolio allocation. Mourdoukoutas outlines the rules for investing in irrational markets successfully.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Intelligent Investing in Irrational Markets by P. Mourdoukoutas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Financial Services. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Rule 1: Don’t Pay Others to Lose Your Money

Abstract: Paying someone to lose your money isn’t fun. That’s why you should either take your financial destiny in your own hands, or choose your financial advisor carefully—the way you choose a medical doctor or a lawyer. Always know where your money is invested and how it performs: read your monthly and quarterly account statements, and meet with your financial advisor regularly to review portfolio performance and investment strategy.

Mourdoukoutas, Panos. Intelligent Investing in Irrational Markets. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. DOI: 10.1057/9781137342898.

“Seek facts diligently; advice never.”

—Philip Carret

On a Saturday morning in the winter of 1985, I was shopping at Mid-Island Plaza Mall in Long Island, New York where I came across Sam, an investment consultant, who was soliciting business for his firm. Sam asked me whether I have any investments. I told him that I had an Individual Retirement Account (IRA) with Long Island Savings Bank.

When Sam heard the word “bank,” his jaw dropped, making me feel a little bit stupid. And when I revealed to him that I earned 7 percent (I wouldn’t dream of it today), he found such returns to be too low, compared to 18 percent I could be earning in the Special Situations Fund, he was promoting.

At that point, I really felt stupid! My mind began racing, calculating the returns I was forgoing by keeping my savings in a money market account rather than handing them to Sam who could deliver twice as much!

To make the long story short, Sam convinced me that he could be doing a better job than me in managing my money. Without bothering to read the Special Situations prospectus, filled with all kinds of footnotes and disclaimers explaining that the 18 percent return was just a fuzzy guess, I quickly signed the necessary documents to hand my savings to Sam—that was my small mistake. The big mistake was that I convinced my then girlfriend and future wife to hire Sam to manage her money, too!

As it turned out, my decision to hire Sam to manage my little savings account was a disaster. First, Sam didn’t work for free; and he didn’t intend to manage my money either. He was a middleman. He did charge me a 4 percent commission for the privilege to turn my money over to the Special Situations fund team, which charged another 2 percent annually to manage the fund. Ouch! Here goes 6 percent of my money for the first year. Second, the fund performed poorly for a couple of years, and when the crash of 1987 came, it lost 25 percent of its value. Double ouch! Coping with this loss was one thing, explaining it to my wife was another!

This personal story states loudly the first rule of investing:

Don’t pay others to lose your money!

Paying others to lose your money isn’t fun; and it isn’t smart either. Yet my personal financial experience is neither new nor unique. The financial press is full of stories about investors lured and fooled by unscrupulous financial advisors and portfolio managers. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, a large group of individual and institutional investors discovered that their financial advisors were also middlemen; they handed the investor money to Bernie Madoff to manage it. But he was running a Ponzi scheme, using the money of new investors to pay hefty returns to old investors. In the end, new and old investors suffered losses in excess of $60 billions.

In 2006–2007, investors poured billions of dollars on homebuilder and financial stocks, following glowing reports about the state of the US housing and financial sectors, losing a great deal of money when the real-estate bubble burst. One of the companies that busted was Lehman Brothers, among the largest investment banks in the world. Another one was Washington Mutual, the sixth largest banking institution in the US, not to mention Countrywide Financial and Merrill Lynch, which were rescued by the Bank of America.

In the late 1990s, investors poured billions of dollars into Internet and telecom stocks following encouraging reports by stock analysts and brokers that eventually trashed in the early 2000s, when the high-tech bubble burst. In the early 1980s, investors poured billions of dollars into oil and gas partnerships that were thought to be secure alternatives to bank Certificates of Deposits (CDs). Between 1983 and 1990, Prudential Securities alone raised $1.5 billion in a series of 35 oil and gas limited partnerships.1 As the price of oil plummeted in the early 1990s and many oil and gas wells turned out to be empty, the only parties that appeared to make money were the brokers who pocketed the hefty commissions.

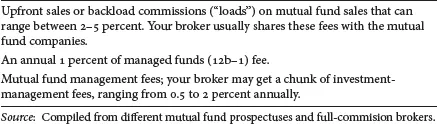

To be fair, these examples are the exception, not the rule. The majority of financial advisors and full commission brokers provide good and sound advice to their clients. The trouble with the financial advising industry, however, is fourfold. First, lack of transparency on how financial professionals are getting paid for their services. By contrast to other professionals who are usually paid an explicitly agreed fee, financial professionals are usually paid with commissions generated by the products they recommend (Table 1.1).

Compounding the problem, commissions and fees on mutual funds are usually buried in disclosure footnotes in multi-page prospectuses, while commissions on whole life insurance products are hidden in computer printouts. But do you think that investors read the fine print, especially rookie investors? I didn’t. I discovered the commissions and fees after I hired Sam to manage my money.

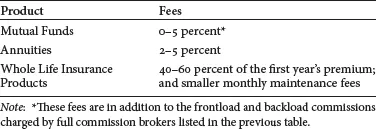

Second, a compensation structure that is open to conflicts of interest—different financial products pay different commissions. Whole life insurance plans, annuities, and limited partnerships usually pay a much larger commission than mutual funds and individual stocks, while money market funds and CDs pay no commission. Commissions further vary across different investment firms (See Table 1.2).

Table 1.1 How full commission brokers get paid

Table 1.2 Commission schedule for mutual funds, annuities, and whole life insurance products as of October 2012

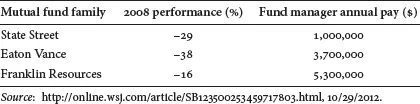

Third, the financial industry is prone to a herd-like behavior. This means that financial advisors follow and replicate the behavior of each other, and end up hurting investors who get into action late. In 2006–2007, for instance, mutual funds poured billions of dollars in financial and homebuilding stocks and suffered heavy losses in 2008 and 2009, as equity markets corrected. Nevertheless, mutual fund managers continued to collect hefty management fees (See Table 1.3). In the fall of 2012, almost every known analyst had a buy recommendation on the stock apple, even as it was descending rapidly from low $700 to the mid-$450! Fourth, industry literature is subject to framing, whereby the track record of different financial advisors and portfolio managers is presented in a way that exaggerates past performance. The performance of US equity mutual funds, for instance, are more likely to look better if it is reported over the period 2009–2013 rather 2008–2013, which will include the 2008–2009 correction.

The above stated problems of the financial industry are confirmed in a study conducted by a group of academicians who investigated the impact of fees on broker performance.2 Specifically, the study found “significant evidence” that commissions paid by mutual funds to brokers skew the brokers incentives in recommending different funds. Worse, broker-sold mutual funds underperformed non-broker peers by 1.13 percentage points for the first year of the investment.

Table 1.3 How major mutual funds fared in the 2008 crash

In short, hiring a financial advisor can be costly, both in terms of commissions and fees and in terms of losses incurred because of the wrong advise. Where does it leave investors who may lack the time and the skills to manage money? What’s the solution?

Here is what I did, back in the early 1980s after Sam lost me money. At the beginning, I was angry with Sam for not explaining to me all the costs and risks associated with investing in the Special Situations fund, as it was part of his job to do. Eventually, I directed my anger to myself. Why did I have to hire Sam to manage my money in the first place? What did Sam know about money management that I didn’t? After all, I did have a Ph.D. in Economics. What sort of credentials did Sam have that made him an investment advisor?

A Series 7 and a Series 63 investment license—the first is a federal license; the second is a NY state license—anyone can take the tests for these licenses. Before long, I did have those licenses myself, I fired Sam, and I began my own journey as a financial advisor and as an individual investor—trading with discount brokers who charge a flat fee per trade (see Table 1.4).

My decision to take my financial destiny in my own hands is neither new nor unique. Legendary investors like Phillip Carret, Warren Buffet, and Peter Lynch relied on their own rather than financial analysts’ research. For years, the Beardstown Ladies’ Investment Portfolio outperformed that of most Wall Street money managers. Ohio University, for instance, had students and faculty manage a five million fund that has performed much better than many of the professionally managed funds.

To be fair, I am not suggesting that every investor follow this path. Some investors simply may not have the time. Others may not enjoy sifting through the maze of scores of different financial products, tax laws that favor one product over another, and government regulations for money that is invested ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Emotions and Intelligence in Investing

- 1 Rule 1: Dont Pay Others to Lose your Money

- 2 Rule 2: Have a Financial Plan

- 3 Rule 3: Know Which Assets to Buy and Sell

- 4 Rule 4: Know Which Stocks to Buy and Sell

- 5 Rule 5: Stay Focused

- 6 Rule 6: Maintain an Intelligent State of Mind

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index