eBook - ePub

Integrating Varieties of Capitalism and Welfare State Research

A Unified Typology of Capitalisms

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Integrating Varieties of Capitalism and Welfare State Research

A Unified Typology of Capitalisms

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book combines the two most important typologies of capitalist diversity; Esping-Andersen's welfare regime typology and Hall and Soskice's 'Varieties of Capitalism' typology, into a unified typology of capitalist diversity. The author shows empircally that certain welfare states bundle together with certain production systems.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Integrating Varieties of Capitalism and Welfare State Research by Martin Schröder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Social Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Welfare State Research and Varieties of Capitalism

This chapter introduces Esping-Andersen’s welfare and Hall and Soskice’s production typologies. Readers who are well accustomed to them can omit this chapter.

1.1 Welfare state research

Drawing on Esping-Andersen (1999: 33), one can define welfare state research as that field of study that is devoted to analysing who manages social risks (mainly divided between: the state, the family or the market) and how these risks are managed. In contrast to varieties of capitalism, welfare state research focuses more on how economic value is (re)distributed than on how it is generated.

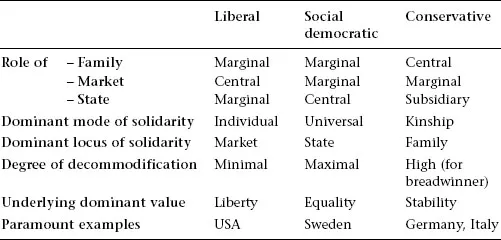

As distributional outcomes of market transactions can be unacceptable for the embedding society, it can create social rights and duties to change these outcomes. It is these rules, their emergence and their effects, which welfare state research examines (Esping-Andersen 1990: 11).1 Differently from varieties of capitalism, Esping-Andersen’s typology explains capitalist diversity out of class conflicts, with the key question being how the working class formed a coalition with different social groups to develop different welfare states (Esping-Andersen, 1990: 18). In Scandinavia, the working class formed a coalition with small, capital-intensive and politically well-organized farmers and then took the middle class on board by providing high-quality social services and public jobs. In liberal countries, the middle class could largely care for itself in the market, so the welfare state became residual, caring only for the poor. In continental Europe, labour-intensive large-scale farmers were in a coalition with conservatives that isolated the labour movement. A state-administered system of welfare benefits tied them to the state by protecting them against social risks. These different class struggles led to three welfare regimes: a ‘liberal’, a ‘conservative’ and a ‘social democratic’ one.2 The table above sums up their main characteristics.

Table 1.1 Three welfare regimes in comparison

Source: Esping-Andersen (1999: 85).

In the liberal regime, markets are the central means of allocation. Welfare programs are largely limited to means-tested poor relief (cf. Bradshaw et al. 1997), distinguishing between one’s ability and one’s willingness to work. Thus, only the undeserved poor (those that are not to blame for their situation) constitute the deserving poor (deserving social assistance). As the bulk of the pensions, unemployment and health system is therefore based on private provision, decommodification3 is low – the state does not protect against the market. The United States is seen as the paramount case for this regime type. Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and the United Kingdom are more ambiguous but fall more in the liberal category than in any other.4

The social democratic regime can be seen as the conceptually opposed model, as it is ‘committed to comprehensive risk-coverage, generous benefit-levels, and egalitarianism’ (Esping-Andersen 1999: 78). The model nonetheless embarked from the same starting point as the liberal one. It preferred a ‘Beveridge’ system of flat-rate citizen entitlements to a ‘Bismarckian’ system, which calculates benefits based on prior earnings. However, whereas the liberal system progressively moved towards residualism, limiting benefits as much as possible, the social democratic countries enlarged their welfare programs towards universalism, taking in the entire population. Accordingly, these countries decommodified workers; they reduced their market dependency to maximize social equality (Esping-Andersen 1999: 78f.). Their welfare state is encompassing, mainly because social benefits are based on citizenship rather than absolute need or prior contributions. Thus, public unemployment, pension, and health schemes cater to everyone, rendering private provision unnecessary, even for the most affluent. In addition, a large public sector generates a high employment rate and a generous public infrastructure of childcare, health and other services, usually provided free of immediate charge. On the downside, the costs of these services entail a high tax burden. Yet, social spending of these states is not the highest in the OECD (cf. OECD 2006: 181). Instead, it is not so much by the overall level of social spending that they distinguish themselves, but by the large dispersion of social benefits towards all social strata. Sweden and Denmark are the purest embodiments of this type of regime, Finland and Denmark resemble it closely.

In the conservative regime, the welfare state is neither residual nor encompassing. It is based on the concept of insurance, as opposed to basing benefits on means testing or citizenship. By contributing to social-security schemes, citizens acquire entitlements in case of sickness, unemployment or retirement. Neither provision of high-quality public services nor means-tested poor relief unsettles the social stratification of these countries (both concerning upward and downward mobility). Instead, by relating benefits to prior contributions, ‘welfare insurances’ stabilize the existing social stratification. Germany is the paramount case of this regime type, whereas Austria, Belgium, France, Italy, Japan,5 the Netherlands,6 Portugal and Spain resemble it closely.

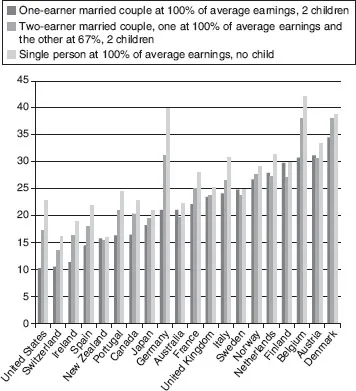

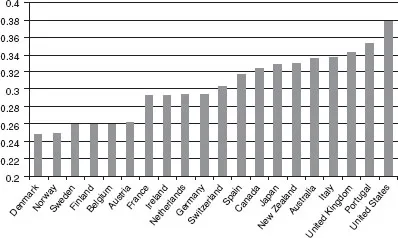

Esping-Andersen arrives at this threefold typology by relying on quantitative data. He sees countries with the highest scores on population coverage and homogeneity of social programs as social democratic. Those with the highest scores on private contribution to health and retirement schemes and the highest degree of means-tested welfare programs are liberal. Conservative countries score highest on the segmentation of welfare programs along occupational status lines. Esping-Andersen (cf. 1990: 69ff. as opposed to 1999) later somewhat refined and rearranged countries. To illustrate differences between the countries and the regime they belong to, the following chart shows wage deductions of three average production workers. The leading bar represents levies for an average worker with a wife, two children and an average wage.

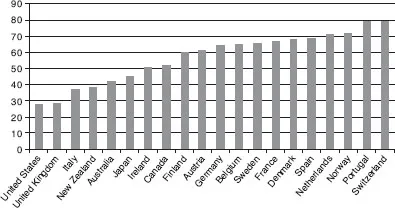

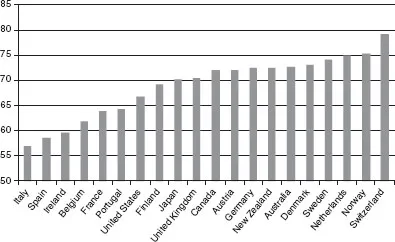

The liberal countries, apart from Great Britain, are all on that half of the countries that levy the lowest financial charges on wages. Under those countries that levy the highest charges, one finds social democratic and conservative ones, with none of the two regime types having clearly more or less heavy deductions than the other. The same average production worker who has to give up a varying share of his wage would probably be happy to hear that he also gets something back. The following chart draws out average replacement rates for the first year of unemployment of a worker aged 40 with an uninterrupted employment record before unemployment, averaged for four different stylised family situations (single and one-earner couple, with and without children) as well as for two earning levels (67% and 100% of average full-time wages).

Figure 1.1 Taxes and social security contributions for different average production workers in 2011

Source: OECD (data from 2012). URL: http://stats.oecd.org.

Again it is the liberal countries, together with Italy and Japan, which replace wages the least in case of unemployment. In short, it is these countries which tend collect the least in the form of taxes and social security contributions, but which also give the least in terms of unemployment benefits. It is conceivable that these welfare state differences, some favouring redistribution more than others, go along with different income structures. The chart on the next page illustrates that this is the case. The bars show the Gini index of household incomes after taxes and transfers; thus they show how unequally income is distributed between households after these have paid for whatever the welfare state costs and received whatever it hands out.

Figure 1.2 Benefit entitlements in the first year of unemployment in 2007

Source: OECD (2009: 76). URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/706364844714.

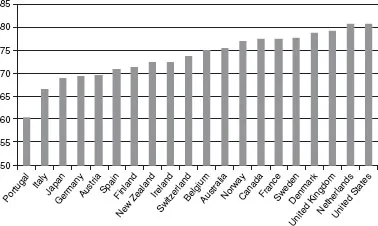

The social democratic welfare states stand out as having the most egalitarian income distribution. The liberal welfare states are on the other side of the figure, they are most unequal, together with Portugal, Italy and Japan. Ireland is an exception to the liberal regime; it is more equal than many conservative countries. Most of the conservative countries are between the two extremes of egalitarian social democratic welfare states and inegalitarian liberal ones. As different welfare regimes exert systematically different charges on employment, while also creating employment in the public sector, they also generate different employment rates. Figure 1.4, which is also on the next page, illustrates this, showing what percentage of all that are of working age are in employment.

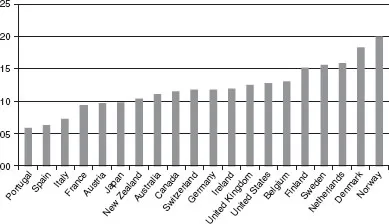

Countries with the lowest employment rates are conservative, together with Ireland, meaning they use their labour pool the least. For a liberal welfare state, the US also has a very low employment rate. Contrary to this, the three social democratic countries of Norway, Sweden and Denmark have the second, fourth and fifth highest employment rates. Switzerland has the highest employment rate and the Netherlands have the third highest, but this is mainly because the Netherlands has a lot of part-time employment. Liberal countries have intermediate employment rates. However, not only is the rate of employment structured through welfare regimes; employment also takes place in different sectors in different welfare regimes. The conservative countries have few service-sector jobs, as their welfare states tax these price-sensitive jobs heavily, financing costly transfers, instead of public service sector jobs, so that overall employment in the (public and private) service sector is low. Figure 1.5 shows this, plotting what percentage of the entire workforce is employed in the service sector.

Figure 1.3 Gini index of household incomes (total population) after taxes and transfers in the late 2000s

Source: OECD (data from 2012). URL: http://stats.oecd.org.

Figure 1.4 Employment rates of the working population (aged 15–64) in 2011

Source: OECD (data from 2012). DOI: 10.1787/emp-table-2012-1-en.

While conservative countries (together with Finland, New Zealand and Ireland) have the lowest proportion of their workforce in the service sector, liberal and social democratic welfare states (together with the Netherlands and France) have the largest service sectors. While both social democratic and conservative welfare states are costly and thereby make work more expensive, depressing work in the cost-sensitive service sector, the charges of the social democratic welfare states do not damage service sector employment as much, because they finance jobs in the public health and social service sectors, as Figure 1.6 shows.

Figure 1.5 Service sector employment as share of total employment (civilians only) in 2009

Source: OECD (data from 2012). URL: http://stats.oecd.org.

The social democratic welfare states (together with the Netherlands) finance extensive employment in health and social services. This makes them different from liberal welfare states, which have no resources to finance large-scale employment in social sectors. The extensive employment that they finance in social services also distinguish the social democratic welfare states from conservative ones, which use their revenue to finance social transfers, instead of public services. So while conservative welfare regimes, especially the Mediterranean countries, have to live with low employment rates, social democratic countries have higher employment due to their large public sector; liberal countries have higher employment rates due to private sector employment.

Figure 1.6 Health and social sector employment as share of total employment (civilians only) in 2009 (2008 for some countries, 2006 for France)

Source: OECD (data from 2011). URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932524032.

For the purpose of this book, these are the main differences of welfare regimes. The classification of welfare states into three regime types had a tremendous impact on the social sciences. As Wincott (2001: 409) argues, ‘more than any other scholar, Gøsta Esping-Andersen has influenced the way in which we view the (comparative) landscape of the welfare state’. But as the preceding figures show, some institutions of some countries diverge from what would be typical for their regime type.7 This provoked criticism again Esping-Andersen’s typology. The following section deals with this criticism, to discuss whether Esping-Andersen’s typology is still a useful way of classifying countries.

1.1.1 Weaknesses of Esping-Andersen’s welfare regime typology

Castles and Mitchell (1993) and Castles (1996) voiced a popular criticism against the three regime types. They argued Australia and New Zealand should be seen as ‘wage-earner’ welfare states, constituting a fourth regime. The labour courts of Australia and New Zealand decommodify workers and provide welfare guarantees via the wage arbitration system, from which a relatively egalitarian wage structure resulted. In this sense, the labour courts of these countries were functionally equivalent to conservative and social democratic welfare states. However, as Castles (1996) himself and Castles, Gerritsen and Vowles (1996) mention, these arrangements have been cut back significantly (also cf. Menz 2005b). In addition, a higher unemployment rate made the primary income distribution, through which these countries achieved a relative degree of egalitarianism, less significant. Therefore, the welfare state structure of these countries, which is liberal, gains importance. So by now, these countries actually have a very inegalitarian income distribution (cf. Figure 1.3). Echoing these arguments, Esping-Andersen (1999: 89f.) refused to add an additional fourth ‘Antipodean’ welfare reg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Welfare State Research and Varieties of Capitalism

- 2 Empirical Indicators and Existing Typologies

- 3 A Unified Typology of Capitalisms

- 4 How Complementarities Stabilize Three Capitalisms

- 5 Diversity’s Source: Three Policy Styles, Three Capitalisms

- 6 What Can a Unified Typology Explain?

- Summary and Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Appendix

- Index