eBook - ePub

Management, Valuation, and Risk for Human Capital and Human Assets

Building the Foundation for a Multi-Disciplinary, Multi-Level Theory

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Management, Valuation, and Risk for Human Capital and Human Assets

Building the Foundation for a Multi-Disciplinary, Multi-Level Theory

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Perspectives on Human Capital and Assets goes beyond the current literature by providing a platform for a broad scope of discussion regarding HC&A, and, more importantly, by encouraging a multidisciplinary fusion between diverse disciplines.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Management, Valuation, and Risk for Human Capital and Human Assets by M. Russ in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Labour Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Management

CHAPTER 1

Team Composition and Project-Based Organizations: New Perspectives for Human Resource Management

Francesca Vicentini and Paolo Boccardelli

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the increasing significance of “projectification” (Lundin & Steinthórsson, 2003) has generated considerable interest in project-based organizations (PBOs), in terms of both academic contributions and general attention. Literature development has been accompanied by the promotion of “projects as means through which to organize workflows across multiple industries” (Maoret, Massa, & Jones, 2011, p. 428). Drawing from different management subfields, including project management, strategic management, innovation, organizational theory, and social networks, scholars have proposed different approaches to the study of PBOs, resulting in the proliferation of multiple perspectives. Maoret et al. (2001) attributed this proliferation to two main theoretical views. The first view considers PBOs as either temporary, that is, formed to accomplish a specific purpose (DeFillippi & Arthur, 1998), or more stable (Whitley, 2006). The second stream of literature focuses on the concept of latent organizations (Scott & Einstein, 2001; Starkey, Barnatt, & Tempest, 2000). This literature includes variations on themes, such as project ecologies (Grabher, 2004), project networks (Jones, 1996; Manning & Sydow, 2007; Soda, Usai, & Zaheer, 2004; Sydow & Staber, 2002), and social networks (Ferriani, Cattani, & Baden-Fuller, 2009; Uzzi & Spiro, 2005), which focus on the enduring relationships among team members over the duration of the project. Despite the relevance, these contributions on PBOs are mainly focused on the study of the macrostructure at the organizational level, but they do not address the human capital involved in the projects and the different levels of analysis involved.

In PBOs, work is often delegated to smaller units, such as teams (i.e., project teams) and crews, because of their ability to integrate individuals with different competences and expertise, resulting in higher-quality decisions and solutions (Harrison & Klein, 2007; Hinsz, Tindale, & Vollrath, 1997, Sundstorm, 1990). Numerous scholars have stated that the shift toward project-based structures has both positive and negative implications for management, employee relations, and employment contracts. For example, Hovmark and Nordqvist (1996) demonstrated that engineers who work in project settings perceive some positive changes in terms of increased commitment, dynamism, communication, and group autonomy. On the contrary, Packendorff (2002) argued that projects rarely consider the previous experiences of individuals. To investigate the effect produced by the human capital forming the project teams (team members), we analyze how successful project teams should be composed, specifically which individual team member characteristics determine a successful outcome. Furthermore, to fill the gap in the analyses of project-based organizations, we consider how project team characteristics may affect the project-level value created for the consumers (project value for consumers).

Team composition looks at the characteristics of individual team members (Levine & Moreland, 1990; Stewart, 2006). One line of research examines aggregated characteristics to assess whether the inclusion of individuals with desirable dispositions and abilities improves team performance. A similar area of research analyzes how heterogeneity of individual characteristics relates to team outcomes. Bantel and Jackson (1989) support the idea that heterogeneity is more desirable than homogeneity (e.g., Stewart, 2006). Theoretical arguments supporting heterogeneity focus on the creativity associated with diverse viewpoints and skill sets; thus, heterogeneity of team members is usually advocated for teams engaged in creative tasks but not for teams engaged in routine tasks (Guzzo & Dickson, 1996; Jackson, May, & Whitney, 1995). To contribute to heterogeneity studies, we investigate whether the individual diversity of team members may explain the key attributes of a project team and the resulting project value created for the consumers. In particular, we investigate the role of specific individual diversity features on the reputation of the project team and the implications on the value to consumers. Accordingly, we address the following research question: To what extent, within project-based settings, does individual diversity affect the team’s characteristics and what are the implications on the project value created for the consumers? We address this question in an attempt to answer Engwall and Jerbrant’s (2003) call for more empirical studies that analyze PBOs, and human capital PBOs stand out as being a highly relevant organizational context for advanced human capital research for several reasons. First, project settings are common work environments for many employees in today’s workplaces (Bredin, 2008). Second, PBOs have certain characteristics that emphasize the importance of human capital, providing challenges for existing models and integrating different theoretical perspectives. Third, PBOs can contribute to the investigation of the effects of project value creation for the final consumers, because projects are open systems that interact with the external environment.

In this chapter, we introduce a multilevel framework (individual and project) that outlines the characteristics of team members selected by project managers to form successful project teams. In the following sections, we first define key theoretical constructs and then develop our research hypotheses for the Italian television drama series industry. We conclude by discussing the broader implications of our multilevel framework and promising framework extensions. This chapter contributes primarily to human capital research and practice because it combines heterogeneity studies and management practices in the specific context of project-based organizations.

Theory and Hypotheses

Core Concepts: Project-Based Organizations and Human Capital

Project-based organizing is becoming increasingly popular in not only traditionally project-oriented construction activities (Bresnen, 1990; Bresnen, Goussevskaia, & Swan, 2004) but also filmmaking and media (DeFillippi & Arthur, 1998; Sydow, Lindkvist, & DeFillippi 2004; Vicentini, 2013), complex products and systems (Hobday, 1998), software development (Grabher, 2004; Ibert, 2004), engineering design (Cacciatori, 2004), and biotechnology (Ebers & Powell, 2007). Pursuant to their pervasive adoption, project-based organizations (PBOs) have been studied in various academic discussions. Project management literature, largely based on normative paradigms, has provided models and practice standards, identifying and disseminating best practices (Packendorff, 1995). By contrast, research on organizations and teams has applied and combined different theories and perspectives (Engwall & Svensson, 2004; Ferriani, Corrado, & Boschetti 2005; Ferriani et al., 2009; Lundin & Söderholm, 1995; Lundin & Steinthórsson, 2003; Maoret et al., 2011; Powell, 2001; Vicentini, 2013; Whitley, 2006), producing some controversial results. A project-based organization is defined as an organizational form in which the project is the primary unit for production arrangement, innovation, and competition, whereas the project can be defined as “any activity with a defined set of resources, goals, and time limit” (Hobday, 2000, p. 872). Investigating the resources within the project, Prencipe and Tell (2001) define project teams as a collection of team members, assembled for a specific purpose, which disbands once the purpose is accomplished. In PBOs, human capital primarily works in temporary project arrangements. Accordingly, we analyze the human capital (HC) construct in terms of human resource management (HRM).

HRM is defined “as the area of management in which the relationships between people and their organizational context are studied” (Brewster & Larsen, 2000, p. 4). In this chapter, the term human capital is used to denote the management of team members involved in the project. The choice of this construct reflects a wish to move away from traditional definitions of HC to provide a more holistic approach to the management of human capital—team members—enrolled within projects. Adopting this approach is particularly relevant for a study of project-based organizations, because they are horizontal, flexible, and decentralized organizational forms (Whitley, 2006). Although the effect of project-based organizing on HRM is acknowledged in several studies, research that focuses specifically on the study of HC in project-based organizations is scarce, as recently reviewed by Bakker (2010). This is because of the lack of consensus on a coherent definition of HRM, which makes it difficult to measure, particularly in a complex project-based context in which there might be confusion on participants’ roles, project tasks, and goals. To overcome this concern, we approach the study of team members as human resources involved in the project, adopting a team composition perspective.

Team Composition and Individual Diversity

It is necessary to study the team composition because the team members are the key resources for the project, and the results connected to the project depend on the team members’ characteristics. Team composition can be regarded as a contextual factor, a consequence, or a causal factor (Levine & Moreland, 1990, p. 593). We consider team composition as a causal factor. Most of the studies that have adopted this causal view reflect the pragmatic desire to create successful groups by selecting people who can work together. For example, Tziner and Eden (1985) investigated the effects of soldiers’ abilities on the team performance of tank crews, demonstrating that the higher the ability levels of each member, the better the group performance. Accordingly, team composition is defined here as the configuration of the team members’ characteristics (Bell, 2007; Guzzo & Dickson, 1996). Prior literature considers team composition to include two stages: a selection process and a reciprocal evaluation process (Perretti & Negro, 2006). The former refers to the way in which an organization or a team manager invites potential members to be part of a new or existing team, whereas the latter relates to the vetting of a candidate for the team (Ilgen, Hollenbeck, & Jundt, 2005). In both cases, team performance plays a pivotal role, as suggested by Barrick, Stewart, Neubert, and Mount (1998) and Cattel (1948). The reason for this strong link emanates from the team composition’s effect on the amount of knowledge, skills, and characteristics team members must apply to the task for which they have combined (Hackman, 1987). In this chapter, we investigate individual diversity as the team member characteristic that is critical to project team member selection in project-based settings. Specifically, we focus our research on experiential task diversity and experiential role diversity as the individual diversity attributes.

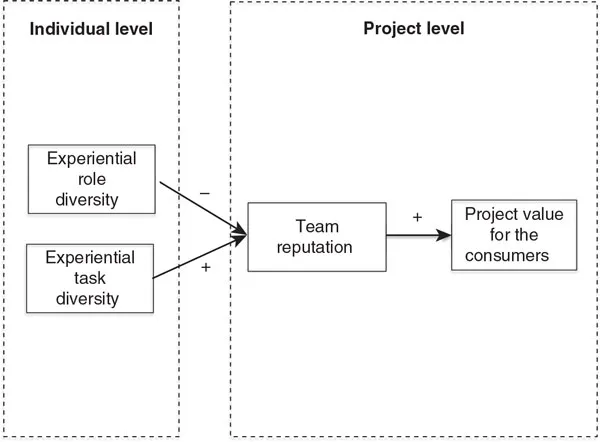

The main goal of the present study is to delineate and test a multilevel model of team composition in project-based organizations. The hypothesized model of relationships, which is depicted in Figure 1.1, incorporates analysis at individual and project team levels.

At the individual level, we look at the experiential task diversity and the experiential role diversity. At the project team level, we investigate the project team reputation and the project value created for the consumers. The former is defined as the opinion about a team formed by another party, including external stakeholders, such as customers, coworkers, and supervisors (Tyran & Gibson, 2008), whereas the latter is the value of the specific qualities of the final project outcome, as perceived by customers in relation to their needs (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2000).

Figure 1.1 Theoretical framework

Experiential Task Diversity, Experiential Role Diversity, and Project Team Reputation

Prior literature conceptualizes experience characteristics as indicators of human capital accumulation at the individual level (e.g., Carpenter, Sanders, & Gregersen 2001; Reagans, Argote & Brooks, 2005) and as proxies for the stock of tacit knowledge at the team level (Berman, Down, & Hill, 2002). Accordingly, individual experiences and experiential diversity are analyzed as potentially unique advantages that may produce higher levels of team performance over time (Bunderson & Sutcliffe, 2002; Carpenter et al., 2001). At the project team level, there is a strong linkage between team member characteristics and the team’s mission. Prior literature suggests that task definitions are the raison d’être for projects (Bakker, 2010; Lundin & Söderholm 1995). However, project tasks are finite; the tasks finish once they are accomplished. One of the most significant consequences of finite tasks is that the accumulated knowledge can be dispersed as soon as the project team is dissolved and team members assigned to different tasks (Grabher, 2004). However, rejecting the idea supported by Packendorff (2002), whereby projects scarcely take into account the previous experiences of the team members, individuals actually accumulate the experiences in their personal repository, and they may make use of them whenever requested in their future careers and tasks. Two different dimensions characterize the experiences: the depth and the breadth of the experiences. Whereas the former involves the accumulation along a sequence of similar tasks and it positively affects professional specialization, the latter results from the accumulation of knowledge and experiences from diverse tasks. We define this last type of experience, experiential task diversity, as the stock of past experiences that each team member accumulates in performing different tasks. There is a trade-off between task specialization and task diversification. Whereas specialization allows team members to complete more repetitions of a specific task within a given time and to gain an in-depth knowledge of the problem domain, diversification allows team members to gain a broader knowledge and improve their abilities to evaluate and use knowledge for other projects (Boh, Slaughter, & Espinosa, 2007). Because team members work in a variety of projects, we support the idea that team members with experience in a diverse set of tasks are more likely to be selected because they can improve task accomplishment. Furthermore, experiencing different tasks allows team members to enhance their latent skills (i.e., talent); over time, these latent skills may represent another individual selection characteristic used by project managers to form project teams. At t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction—What Kind of an Asset Is Human Capital, How Should It Be Measured, and in What Markets?

- Part I: Management

- Part II: Valuation and Risk

- Index