![]()

1

A Mystery Unfolds

17 June 2000 was a momentous day in the vexed and complex history of the city of Granada. Two high-ranking Catholic priests, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the man who was to become Pope Benedict XVI, and the Archbishop of Granada, Don Antonio Cañizares, met in the Vatican. The two men were already friends, as they both attended regular meetings of the Congregation of the Faith, of which Ratzinger was the prefect, but their meeting on that June day was an official rather than a personal one. On this occasion the cardinal handed over to Don Antonio 235 lead disks, an ancient piece of parchment, a bull issued by Pope Innocent XI, two lead plaques which acted as covers for some of the lead disks and 14 boxes of lead items of different sizes, together with 468 postcard-sized photographs of both sides of the lead disks, plus 20 CDs of historical documentation (Figure 1.1). Shortly after this bizarre encounter, on 28 June, journalists gathered expectantly in the salons of the abbey of the Sacromonte1 in Granada to witness the long-awaited return of these strange artefacts, in the presence of the archbishop, the chapter of the abbey and a representative of the Spanish bank Caja Sur, which had financed the undertaking. This act of restoration revived an ancient memory, one which brings vividly into focus the extraordinary events that took place in the city nearly half a millenium ago: the remarkable archaeological artefacts known as the Lead Books of Granada had come home. They harbour a mystery as compelling as the occult lore that cloaks the lost Jewish Menorah and the Turin Shroud, and they have bemused and frustrated scholars and intellectuals for centuries, while remaining one of Spain’s best-kept secrets to the present day. Their life began over 400 years ago in the former Moorish city of Granada and wove together the lives of some exceptional people of differing race and religion. The importance and resonance of the Lead Books remain undiminished, as the secrecy still surrounding them confirms. This book tells their unique story, which embraces theology, history and literature, moving from the time of their astonishing discovery on a hill outside Granada to the present, and investigates the riddle of their creation, delving into the shadowy lives of their alleged authors and the many intrigues and enigmas surrounding them. It explores a set of complex circumstances and motives born of the racial and religious strife that gripped Spain in the sixteenth century, and pursues the reasons behind the mystery which continues to veil the Lead Books today.

Figure 1.1 Cardinal Ratzinger hands over the Lead Books in Rome (abbey of the Sacromonte archive)

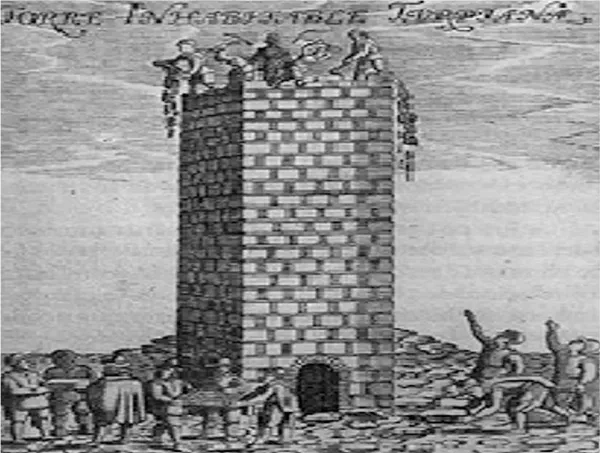

To begin to make sense of that June meeting in 2000 between the two members of the Congregation of the Faith, we must go back in time and set the scene in the Armada year, 1588, when the minaret of the old mosque in Granada, later known as the Torre Turpiana,2 was demolished during the construction of the new cathedral. If you visit the cathedral today you can still see a white marble plaque, on view in the crypt close to the tomb of Mariana Pineda, which commemorates the unusual discoveries made by the workmen who were taking down what the Granadans knew as the Old Tower, Torre Vieja, attributed by some to the Romans and by others to the Phoenicians. It was formerly the minaret of the Great Mosque of Granada. Beside it was a well, described by the local historian Bermúdez y Pedraza as ‘so deep that some say it has no bottom’ [tan hondo que algunos dicen no tiene suelo],3 and together they were considered to be two of the main curiosities of sixteenth-century Granada. However, the tower stood in the way of the proposed new third nave of the cathedral, and the Archbishop, Don Juan Méndez de Salvatierra, ordered it to be demolished (Figure 1.2).

The upper part of the tower was recent and built of brick, serving as a bell tower, but the minaret proper was ancient and took a great deal of work to dismantle. After some difficulty, some of the stonework was finally removed on the festival of the Archangel Gabriel, 18 March 1588, and on the following day, the festival of Saint Joseph, a lead casket came to light, hidden in a fragment of broken masonry.

When the casket was opened, the workmen found that it contained some puzzling items. There was a small panel bearing an image of the Virgin Mary, a fragment of linen, a small piece of bone, a folded parchment and some blackish-blue sand, all covered with a piece of linen cloth to protect them. The discovery of the casket aroused great excitement among the Granadans, but what caused the greatest commotion was the parchment, which consisted of text written in Latin, Arabic and Castilian. According to some of the text, the contents of the casket consisted of the bone of the first martyr, St Stephen, the cloth the Virgin dried her eyes upon at the Crucifixion, and a prophecy by St John the Divine relating to the end of the world. Yet the parchment caused such trouble to decode that eventually expert translators were called in and managed to decipher the full script. It appeared that the prophecy of St John had been translated into Castilian by St Cecilius, who described himself as the first bishop of Granada in the first century AD. It was highly puzzling that an early saint should be able to write in both Arabic and Castilian, since the latter language had not existed at such an early time, but, nevertheless, Granada was delighted to know that he was its first bishop. Seven years later, in 1595, treasure seekers digging on the Valparaíso hill outside Granada, later known as the Sacro Monte, came across a strip of lead engraved in archaic Latin, which claimed that the cremated remains of an early Christian martyr were buried there. The excavation of the site began at once, and revealed two more lead plaques, one of which announced that Saint Tesiphon, one of the seven bishops of Rome, who was apparently an Arab convert to Christianity, had written a book on lead tablets called the Fundamentum Ecclesiae, or fundamental doctrines of the Church. Amid great excitement ashes, presumed to belong to the saint, were discovered on 13 April 1595, and then, on 22 April, something even more unprecedented happened.

Figure 1.2 Workmen demolishing the Torre Turpiana, seventeenth-century engraving by Heylan (abbey of the Sacromonte archive)

The first of the strange Lead Books of the Sacro Monte was discovered beneath a large stone, still visible today. It was wrapped in a folded lead cover and comprised five round plates four inches (10 cm) across, hinged together by a twist of lead. These plaques were inscribed in Arabic on both sides and coated in a sticky preservative. The excavators could not read Arabic, but on the inside was the Latin title, which translates into English as The Book of the Fundamental Doctrines of the Church Written in the Characters of Solomon. This was presumably the book authored by Saint Tesiphon referred to in the previously discovered parchment. The new revelation was celebrated with parties, fireworks, artillery salutes from the Alhambra and general bell ringing. No one had yet read the book, but this did not seem to matter. Next, the lead plaque relating to Saint Cecilius himself was found, and the Sacro Monte was destined to become a famous place of pilgrimage. Even the celebrated poet Luis de Góngora wrote a sonnet in honour of the forest of wooden votive crosses erected on the site.4

Over a period of many months, a total of 22 lead books were found on the hill. Due to the complexities of the texts, which were written in the same three languages as the parchment, professional translators were called in, who declared that the books contained doctrinal material of the greatest importance, including the instructions and sayings of the Virgin Mary, St Peter and St James, accompanied by references to the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin. Granada badly wanted to believe in the Lead Books, and experts of all kinds, including scribes, parchment makers, anatomists and charcoal burners, were called in to scrutinize the relics, but what proved decisively to Granadans that the finds were genuine were the strong supernatural predictions of their discovery. As long as 50 years before the excavations took place, mysterious lights had repeatedly been observed over the site, and this was considered conclusive proof of the impending divine revelations.

Although King Philip II was very ill at that time, he was fascinated by the affair and took great interest in the translations, but rumours began to circulate that the relics were not authentic, and a number of scholars and churchmen appeared to corroborate this. Yet a group of local theologians, including the new archbishop of Granada, Don Pedro de Castro, had already decided that the relics and texts were genuine. The scholar and poet Arias Montano summed up the situation when he wrote to Archbishop Castro in 1597 stating that the finding of the relics and lead disks was a ‘a very serious matter … the most important in the world today and perhaps there has been none more important for many centuries’ [negocio gravísimo … el mayor que hoy día tiene el mundo y quizá no lo haya tenido mayor en muchos siglos].5

However, the Vatican, fully apprised of this situation, delicately yet firmly applied pressure to have the finds investigated further. After a period of many years, the Lead Books were taken to Madrid for examination in 1631, and ultimately, amid great protest, were removed to Rome, where finally, in 1682, they were condemned for Islamic heresy. This might have been the end of the matter, and, effectively, they did vanish from public knowledge, lying forgotten in the secret archives of the Vatican, until one day in the year 2000, when Cardinal Ratzinger mentioned to his friend Archbishop Cañizares that the archives contained some very curious and ancient texts from the diocese of Granada.6 The archbishop seized the opportunity to request their return to their place of origin, and the wheels were set in motion, culminating in that meeting on 17 June 2000 when they were officially handed over to Cañizares. This, ironically, was an act treated with some suspicion by certain Granadans, who feared they might not actually have been given the originals. For the first time, these singular literary documents were exhibited in the cathedral of Granada, and were then taken to the abbey of the Sacromonte, where they were placed under tight security in the Secret Archive of Four Keys. A small number of the lead disks were put on display and can be seen today by visitors to the abbey museum. At the handover ceremony, the future pope told those present: ‘We have given back a historic treasure of humanity, and above all, of the diocese of Granada. Saint Cecilius was the first bishop of Granada, one of the seven companions of Saint James the Greater, evangelist and patron saint of Spain’[Hemos restituido un tesoro histórico de la humanidad y, sobre todo, de la diócesis de Granada. San Cecilio fue el primer Obispo de Granada, uno de los siete acompañantes de Santiago el Mayor, evangelizador y patron de España].7

There is no doubt that the Lead Books caused a religious sensation, both locally and in Catholic Europe too, at the time of their discovery and long after. Yet the mystery and secrecy surrounding these unusual texts from their inception to the present day has meant that they have been studied within certain limitations by a small group of scholars working mainly in Spain, England and the Netherlands, and have remained generally unknown to the wider public. These limitations have generally been those imposed by the Granadan church authorities themselves, to the degree that there has been a quite understandable perception that access to the Lead Books was being intentionally obstructed by the Church. An article written on webislam in April 20078 outlines the problems scholars have encountered since the return of the texts to their home city. Why, asks Alejandro V. García, is the Granadan church resisting allowing experts to study the plomos, as they are known? What is the mystery? Are they the originals or mere copies? Do the originals exist or were they destroyed according to the papal bull? García writes that, when the priest in charge of the exhibition of the artefacts in the cathedral, Javier Martínez Medina, was asked whether these were indeed the originals, he prudently replied that he was only in charge of preparing the exhibition of the materials handed over by the Vatican. Professor Miguel J. Hagerty, recently deceased professor of Arabic Translation and Interpreting at the University of Granada, requested permission for a committee of experts to examine the holdings of the abbey to certify them as authentic, and he was also one of the experts who tried fruitlessly to examine the books. He was unsuccessful on both scores. The reasons given by the abbey authorities for hindering access to the lead disks were that there is a lack of appropriate infrastructure, that the abbey is in a poor state, and that they lack custodians to supervise and guarantee the safety of the precious artefacts. Another view is that the church authorities were forbidding scholarly access on the grounds that the original official prohibition by the Vatican was still in force!

Recently, however, the Lead Books have once again attracted the attention of Granada. The year 2010 was the 400th anniversary of the founding of the abbey of the Sacromonte, which continues to house the Lead Books and relics, and, in January of that year, the current archbishop of Granada, Don Francisco Javier Martínez, announced that the Lead Books could be available at the end of the year in a critical edition for public consultation which is being prepared by two Dutch scholars, Professors Gerard Wiegers and Pieter van Koningsveld. The Lead Books will also be digitalized and will demonstrate, according to the archbishop, that the Church ‘is not afraid of history, and to view it with fresh eyes always enriches our experience’ [no tiene miedo a la historia y mirarla con unos ojos limpios siempre enriquece a nuestra experiencia].9 The edition is still in preparation.

The current cultural climate of Europe, Spain and Granada in particular makes the telling of this extraordinary story even more vital. Spain is seeing an upsurge of Muslim immigrants who are living permanently in the country, and the government is working hard to integrate Muslims into mainstream society to prevent radicalization and reduce the sense of alienation that fosters religious extremism. Tensions are high between Spain’s non-Muslims and Muslims, with both sides torn over issues of religious versus cultural identity. Granada has a unique place within Spain’s history as the last Moorish stronghold to fall to the Christians, and its past lives on in the present, not only in the awe-inspiring palace of the Alhambra, but in the everyday texture of life in the city, where the old Moorish quarter of the Albaicín is full of teashops, butchers and bakeries selling Muslim food, signs in stores wish passersby ‘Happy Ramadan’ and locals use Arabic to greet each other. The white minaret of the new Great Mosque of Granada is a testament to Spanish Muslims’ pride in their history, and to the strength of their faith. Unfortunately, these Muslims are also associated in the minds of many with those militants who swore loyalty to Al-Qaeda, and stated their motivation for the terrible March 2004 bombings in Madrid as part of the continuing jihad in the land of Tarik Ben Ziyad, the Moorish soldier who led the initial invasion of Iberia in 711.

The minaret of the new mosque echoes that original minaret whose demolition in 1588 revealed the relics hidden there. The story surrounding them and the discovery soon after of the Lead Books brings the strangeness and importance of these events into sharp definition, and initiates a dialogue between the past and present which has relevance for the future. To unravel the tangled web of intrigue and enigma which swathes the discoveries, we must ask some crucial and fundamental questions – what precisely were these relics and texts? What did they look like and how did they find their respective ways to an ancient minaret and a rocky hillside? Who made them, and why?

![]()

2

Books of Spells or Sacred Revelations?

The Torre Turpiana relics

After nightfall, four men are walking with great stealth through the Moorish silk bazaar in Granada towards the gate of Jelices, from which point they can observe the construction works for the new cathedral. No one works in the silk markets at night, and all is quiet except for the voices of the cathedral guards. The old minaret of the mosque rises before them, no longer needed since the magnificent new bell tower has been built. It is half-way through demolition, stone by stone, from the top downwards so that its old ashlars can be reused, and to avoid damaging the flooring of the cathedral. The men scrutinize the tower carefully, attentive to the conversations and laughter drifting towards them from the guards in the central part of the building. One of the four is holding a casket hidden under his cloak, and, while his three companions create a disturbance to distract the guards at the other end of the cathedral, the man with the casket enters the tower through the old minaret and climbs a narrow inner staircase, finally emerging at the top, from where he can see the Alhambra and all of the city lying beneath him in the darkness. ‘Allah is great!’ he whispers, searching hurriedly in hope of finding a stone loosened by the demolition. He is in luck, and hurriedly removes the stone and mortar, setting the casket in the empty hollow before replacing the stone carefully and descending the stairs to retrace his steps through the silk bazaar and calm the feigned dispute his friends are embroiled in.

This tense, exciting episode is taken from Part 3, chapter 52 of the contemporary Spanish novelist Ildefonso Falcones’ recent bestseller, La mano de Fátima [The Hand of Fatima].1 His fictional protagonist’s involvement in the Torre Turpiana affair which took place in Granada in 1588 is one of the central plot strands of this 950-page novel, and the scene I have paraphrased above is cleverly constructed and entirely plausible. It is, alas, probably as close as we may get to reconstructing the manner in which the relics found their way into the ancient tower, in the absence of any new documentary evidence. But life is at times as strange as fiction, and the fact is that on 19 March 1588 a lead cask...