![]()

Part I

Linguistic Diversity: Origins and Measurement

![]()

1

Linguistic Theory, Linguistic Diversity and Whorfian Economics

Nigel Fabb

1.1 Introduction

I begin this chapter by illustrating what theoretical linguists do and why generative linguistics in particular has argued that linguistic data is more abstract and more complex than at first appears. I then illustrate language diversity by comparing aspects of two languages, English and Ma’di, an East African language. Sections 1.2 and 1.3 focus on specific aspects of linguistic data, which are chosen to illustrate general points about linguistic theory and linguistic diversity. In Section 1.4, I briefly note several different theories of linguistic diversity which explore why languages vary and whether variation is limited by internal (psychological) or external (cultural) factors. In Section 1.5, I examine the ‘Whorfian’ hypothesis that linguistic form has a causal relation with thought and behaviour, summarize some of the relevant psycholinguistic work and then examine some articles by economists which claim causal relations between linguistic and social variation. Based in part on what I have said about linguistic theory and linguistic diversity, and in particular the abstractness of linguistic data, I will argue that the economists’ claims cannot be sustained. In the final part of the chapter I discuss some ways in which stylistic variation within a language might affect thought.

1.2 Abstract linguistic form, and the rules and conditions which govern it

Linguistic theory is an attempt to understand the regularities and patterns which can be found in language. The fundamental discovery of modern linguistic theory is that a word or sentence can have a complex and multi-layered abstract structure; our knowledge of language is knowledge of that abstract linguistic form. These discoveries about language usually take as a starting point Noam Chomsky’s (1957) Syntactic Structures, and in the first part of this section I outline some of the ideas presented in that book. I then illustrate the evidence for abstract linguistic form with a number of examples, because linguistics is always a matter of how specific problems are discovered and solved, and how these solutions fit into a larger theory of language.

1.2.1 Chomsky’s Syntactic Structures

Modern linguistic theory begins with the publication of Noam Chomsky’s 1957 book Syntactic Structures which was consolidated in his 1965 Aspects of the Theory of Syntax; in this section, I summarize some of the aspects of the early ‘generative grammar’ or ‘generative linguistics’ initiated by these books. Though no one still pursues this particular theoretical model, many of its findings remain true of theoretical linguistics. Chomsky begins by arguing for a distinction between two types of sentence: grammatical and ungrammatical. Ungrammatical sentences are combinations of words which are not accepted as sentences by native speakers, with the proviso that this is not a judgement based on meaning or social acceptability: that is, that speakers can make judgements of grammaticality based just on the form of a sentence. Chomsky proposes that a grammar of a language should be a device which generates all and only the grammatical sentences for that language. This type of grammar is identified with a psychological capacity, the human knowledge of language. The grammar of each language is a variation on principles of a ‘universal grammar’ which is innate and shared by all humans; the universal grammar offers ‘switches’ which are turned on in some specific combination to produce the grammar of a specific language.

Chomsky’s goal is to establish what kind of grammar will generate the grammatical sentences of English (hence ‘generative grammar’). He notes that English comprises an infinite number of different grammatical sentences which must be generated by a finite device; this is possible because the grammar allows recursion, where for example a sentence can contain a sentence repeatedly, without limit. A sentence is a sequence of words, but there is evidence that these words are grouped into constituents which are subject to generalizations. Thus the grammar does not just generate the sequence of words which makes up the sentence, but generates a structured sequence, organized into hierarchically arranged constituents (see Rizzi, 2013 for detailed discussion). For example, the sequence of words (in the title of each figure) in Figures 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 are given a structure by the grammar shown schematically as a tree structure. As can be seen, the structures differ in whether they allow the pronoun and John to refer to the same person (note that the structures are simplified and schematic, and not a full linguistic structure for the sentences).

Note that his in Figure 1.1 can be interpreted as referring to John (but can also be interpreted as referring to someone else), while in Figure 1.2 he cannot be interpreted as John. This is not just a matter of which pronoun is used, because in Figure 1.3, he can be interpreted as John. This difference cannot be derived from the sequences directly, either from the sequences of words or from the number of words between the pronoun and the name. Instead, the difference is in how they are hierarchically related in the constituent structure as shown in the three figures. The explanation is based on a discovery made by theoretical linguists about the hierarchical relations between items in a tree, as I now explain.

Figure 1.1 His mother loves John (‘his’ can be interpreted as ‘John’s’)

Figure 1.2 He loves John (‘he’ cannot be interpreted as ‘John’)

Figure 1.3 That he is hot bothers John (‘he’ can be interpreted as ‘John’)

Figure 1.4 C-Command

A node in a tree dominates other nodes (i.e. all the nodes underneath it). The nodes immediately underneath a node (i.e. with no intervening nodes) are ‘immediately dominated’ by the node. So for example the topmost S dominates all the nodes in the tree, but immediately dominates only a noun phrase (NP) and a verb phrase (VP) in Figures 1.1 and 1.2 and a sentence (S) and a VP in Figure 1.3. The discovery about language is that there is a special kind of relation, called ‘c-command’, based on the relations of dominance (the nodes under a node) and immediate dominance (the nodes immediately under a node). Given a node X and a node Y which immediately dominates X, X c-commands all the nodes dominated by Y. Thus for example in Figure 1.4, B c-commands B, C, D and E, while E c-commands only D and E (the definition as given here means that a node always c-commands itself).

In Figure 1.1, the NP his does not c-command the NP John. But in Figure 1.2, the NP he does c-command the NP him. This is why co-reference is possible in one case but not the other. The rule for English (and most if not all other languages) is as follows:

A name cannot be c-commanded by a noun phrase (NP) which co-refers.

This rule is what prevents the pronoun in Figure 1.2 referring to the name: the pronoun c-commands the name because its NP is immediately dominated by the node S which dominates the name, and c-command prevents co-reference. In Figures 1.1 and 1.3, the NP which is the pronoun is buried deeper in the tree and so does not c-command the name; hence co-reference is possible. (At this point, I note again that this is a simplified account: the relevant structural relation is more complex than just ‘c-command’, here and elsewhere in the chapter, and has been subject to theoretical revision.) This example demonstrates two fundamental principles of linguistic theory, agreed by almost all linguists: that there is abstract form (in this case, the abstract constituent structure which holds of the words), and that linguistic principles refer to the abstract constituent structure.

Chomsky wants linguistic theory to formulate a grammar of a language which can explain aspects of the language, such as the co-reference possibilities described above. Another thing to explain is the ambiguity of the sequence of words visiting relatives can be annoying. This is ambiguous because there are two different constituent structures for the same sequence, one of which means that relatives are visiting (the subject is an NP referring to the relatives and can be restated as relatives who visit) and the other which means that relatives are being visited (the subject is a kind of clause referring to the visiting and can be restated as to visit relatives). To explain this fact demands that we accept some degree of abstractness, in the form of different constituent structures, and that the constituent structures can play a role in determining the meaning of the sequence of words.

A fundamental part of the Syntactic Structures theory is ‘transformational rules’ which relate different structured sequences to one another; because of the importance of these rules in this version of the theory it was called ‘transformational generative grammar’. Thus the sequence the man hit the ball has the same truth conditions as the ball was hit by the man, and this can be achieved by a mechanism in the grammar (a transformational rule) which takes a structure and rearranges it: the phrase before and the phrase after the verb are changed in their locations in the constituent structure. Note that this rule affects multi-word constituents and not individual words, thus showing that knowledge of a sentence is knowledge not just of the sequence of words (audible on the surface) but knowledge of the structural relations between words. We have seen that there is an abstract level at which a constituent structure holds of strings of words. Transformational rules show that there must be more than one such level, such that a final string of words can be derived from distinct constituent structures at different levels, related by transformational rules. Chomsky concludes: ‘to understand a sentence it is necessary (though of course not sufficient) to reconstruct its representation on each level’. There are multiple abstract representations on different abstract levels which underlie the surface sentence, and these abstract representations are claimed to be psychologically real. This has significant consequences for our understanding of what language and ‘knowledge of language’ are, with problematic consequences for Whorfian theories under which linguistic forms are caused by or cause extra-linguistic thought and behaviour.

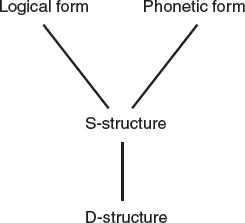

Distinct ‘levels’ are hypothesized as domains within which certain types of representation exist, and rules map representations from one level to another: each sentence has a representation on all of these levels. One model of levels of representation, the ‘government and binding theory’ model (Chomsky, 1981), is shown in Figure 1.5.

Figure 1.5 Government and binding theory

In this model, phrase structure rules build constituent structures at D-structure, and transformational rules produce derived constituent structures at S-structure. The constituent structures at S-structure are then subject to rules which produce representations of sentences, which at the level of phonetic form constitute speakable sentences; separately, the constituent structures at S-Structure are subject to rules which form representations of sentences at the level of logical form which can be interpreted as meaningful (e.g. using the language and form of predicate logic). As we will see shortly, two languages can have the same rule operating at different levels, leading to different surface forms (but with an underlying similarity)...