![]()

1

Theoretical Framework

Abstract: The theoretical framework we laid out in the first book of this series used several components of sustainable development—geography, well-being, economy, and environment. Hence we can talk about both the natural and human forces that shape these components, as well as the policy implications that arise from a study of these factors. In this chapter, we discuss the need for a new type of economic geography model.

Hsu, Sara, Michio Naoi and Wenjie Zhang. Lessons in Sustainable Development from Japan and South Korea. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. DOI: 10.1057/9781137340986.0006.

The theoretical framework we laid out in the first book of this series used several components of sustainable development—geography, well-being, economy, and environment. These are all aspects that are explored in detail for Japan and South Korea later in this book.

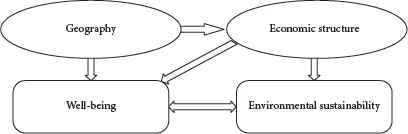

Our theory states that geography, as a preceding factor that is not easily changed, influences well-being and economic structure, through the presence or absence of natural resources, ease or difficulty of transportation, and access or lack of it to the outside world. The economic structure in turn impacts environmental sustainability and well-being through the way it modifies land, air, water, and resources during production and consumption. Well-being and environmental sustainability mutually affect one another; those with higher levels of well-being have the opportunity to (but do not necessarily) improve the environment, while higher levels of environmental sustainability improve well-being. Human policies also shape and are shaped by sustainable development. As a result, we can talk about both the natural and human forces that shape these components, as well as the policy implications that arise from a study of these factors.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the way in which these factors are related.

These factors have been accounted for in the vast literature on economic geography, which is an extremely diverse field that we do not discuss extensively in the first volume. We will touch on some of it and discuss how it influences our model. This exact model however has not been iterated in the literature but most elements of it have been discussed.

Why is a new model of sustainable development/economic geography needed?

FIGURE 1.1 The interaction of geography, economic structure, well-being, and environment

Source: The author.

First, in the first volume of this series we mention the importance of the Krugman (1991) economic geography model. This model illustrated the reasons why countries developed an industrial core and an agricultural periphery due to differences in demand that in turn resulted from the distribution of manufacturing. Manufacturing distribution is dependent on transportation costs, economies of scale, and the relative contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP. Although this model was considered to give a satisfactory explanation of how economic systems arise, with geography as a major factor, the Krugman model has been criticized for leaving out some important components of economic geography, including: aspects of the social division of labor, information flows and search patterns in the labor market, region-based learning, and regional competitive advantages (Scott 2004). It has also been criticized for being intentionally abstract rather than concrete, and it differs from traditional geographical research in its lack of social context.

Second, economic models that deal with geography stress the role of factor prices and transactions costs. These models include not only the Krugman’s model but also models by Gallup, Sachs, and Mellinger (1999) and Helpman (1998). The goal of many of these types of models is to explain patterns of growth or trade, as well as factor and output prices without accounting for social forces and environmental impacts. Marxist models attempt to make up for the shortcomings of these neoclassical economic geography models by emphasizing that imbalances due to social relations still remain. Even so, considerations of the environment and general well-being are normally excluded from the models of both types. Additional forms of economic geography—evolutionary economic geography, which studies the role of geography in the evolution of economic systems—and institutional economic geography—which studies the changing economic landscape accounting for institutions and geography—do not speak to these lacunae either. We consider a model of economic geography to be an important basis for a model of sustainable development; therefore, well-being and environmental sustainability must be included in such an approach.

Third, the sustainable development literature itself most often falls short of addressing all elements of geography, economy, well-being, and environment. This is in part due to the plethora of definitions of the term “sustainable development” in existence—about 70 existed as of the early 1990s (Holmberg and Sandbrook 1992); one can only imagine that the number has grown since then. The many definitions reflect the myriad aspects of development and sustainability itself—production, trade, growth, technology, population, environment, social institutions, biological diversity, equity, finance, political administration, and so on. In addition, the sustainable development literature as it relates to economics has focused on the relationship between environment and economic, or specifically market, structure, and has been put forth mainly by environmental economists (Castro 2004). There is thus less of an emphasis on well-being, as drawn out by the UN Millennium Development Goals; when there is discussion of well-being in the sustainable development literature, there is often an absence of one or more of the other elements—geography, economic structure, or environment. Finally, the sustainable development literature as it relates to the environment in general frequently neglects both economic and well-being aspects of development.

Why is it important to include all of these elements into a sustainable development model? The reason we propose a new model is that one must consider geography, economic structure, environment, and well-being in one model since policies associated with sustainable development should either address or “do no harm to” all of these elements. A policy, for example, that improves the environment by moving indigenous people off the land in a rain forest can negatively impact both well-being and economic structure. A policy that strives to improve individual well-being, reduce poverty, and improve the environment by building solar farms in a shady area may fail by neglecting to take into account geography. Therefore all of these factors matter in building sustainable development. Without one or more of these elements, the model would be lacking.

Our model deals with the interaction of these factors. The only factor that more or less remains the same throughout is geography, since the landscape and, to some extent, the given natural resources are relatively unchangeable (resources can be used up but not easily regenerated). Well-being and environmental sustainability are “results” of geography and economic structure that influence one another. We shall draw out the technical details of the model further in the third volume of this series.

Now, we turn to the elements of sustainable development in Japan and South Korea, looking at environment, energy conservation, national land resource, biodiversity, production, livelihood, health, science and technology, urban and rural culture, well-being, governance, participation national resource accounting, property rights, energy self-sufficiency and international politics of energy markets, and the implications for the rest of the world for both countries. This is the same template that was used in the first book in this series, on Taiwan and China, so that all countries in the series can be easily compared against one another.

![]()

2

Sustainable Development in Japan and South Korea

Abstract: In this chapter, we discuss sustainable development in Japan and South Korea in terms of geography, well-being, economic structure, and environmental sustainability.

Hsu, Sara, Michio Naoi and Wenjie Zhang. Lessons in Sustainable Development from Japan and South Korea. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. DOI: 10.1057/9781137340986.0007.

Introduction to Japan

Japan is comprised of an island chain running between the North Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Japan, with a land area slightly smaller than California in the United States (CIA 2014). The country contains volcanoes and experiences air and water pollution, as well as depletion of natural resources. It is highly developed, with one of the longest life expectancies in the world, a 99% adult literacy rate, and a 100% access to improved drinking water and sanitation facilities. The economy, however, has lagged since the 1990s and continues to have an unemployment rate above 5% for both males and females.

Japan and sustainable development

A. Environment

We begin with a discussion of the environment, which includes various aspects of air, water, and soil pollution, as well as waste management and pollution control policies in Japan. As its habitable area is extremely limited (about 70% of the land is mountainous), its industrial activities have been concentrated within a limited geographical area. This has caused serious environmental problems particularly during the period of rapid economic growth in the 1950s and 1960s.

Air pollution

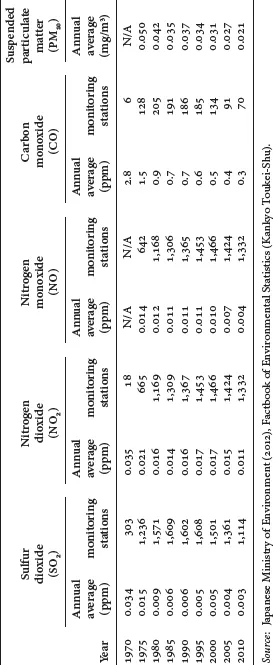

Overall, air quality in Japan has significantly improved over the last few decades, especially in the 1970s and early 1980s. Table 2.1 shows trends in average air pollution concentration of five pollutants (SO2, NO, NO2, CO, and PM10) together with the number of monitoring stations for each pollutant.

From Table 2.1, we can see that levels of pollution concentrations drastically decreased between 1970 and 2010. For example, the concentration of sulfur dioxide (SO2) decreased by more than 90% between 1970 and 2010.

In the past, Japan faced serious air quality degradation due to growing industrial activities in certain metropolitan areas. For example, in the late 1960s, major Japanese industrial cities recorded annual average concentrations of SO2 ranging between 0.06 and 0.11 parts per million (ppm) and this caused various health risks to inhabitants as well as to those living nearby. A notable example is Yokkaichi asthma. In 1955, petrochemical complexes were constructed in Yokkaichi area in Mie Prefecture and, soon after the start of plant operations, local inhabitants began to suffer from asthma and pulmonary emphysema. Certified pollution-related asthma patients were recorded as more than 2,000, among which more than 40% were children aged less than ten years (Hoshino 1992).

TABLE 2.1 Air pollution and monitoring stations in Japan, 1970–2010

As a reaction to the increasing air pollution levels, systematic pollution control measures were introduced in the 1960s. The first national law to prevent air pollution, the Smoke and Soot Regulation Law, was enacted in 1962, and specifies the amount of pollutants allowed for discharge within certain designated areas. In 1968, this was replaced by more comprehensive regulations under the Air Pollution Control Law, which provides uniform regulations throughout the country. Since then, the law has been amended several times, expanding the list of regulated pollutants and introducing stricter emission standards. As a result, these pollution control measures have been successful in reducing pollution over the 1970s and early 1980s.

In general, Japan’s approach relied mainly on setting specific limits to the amount of pollutants, both by national and local governments, rather than on using market mechanisms to reduce pollution (Yaguchi and Sonobe 2002). The effective enforcement of emission controls can be attributed to an extensive air pollution monitoring system. The monitoring system is called the Atmospheric Environmental Regional Observation System (AEROS). Currently, there are 1,581 monitoring stations covering all 47 prefectures in Japan (see Table 2.1 for details).

Compared with air pollution substances that have strict plant-level emission limits, greenhouse gases do not have individual emission limits so far. A recent survey by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment (MOE) shows that carbon dioxide (CO2) is the major source of greenhouse gas emissions. Levels of CO2 emissions have fluctuated and the current level is almost the same as that in the late 1990s. Levels of methane, nitrous oxide, perfluoro-carbons (PFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride emissions have declined over the period. Levels of hydrofluoro-carbons (HFCs) have fluctuated (Ministry of Environment 2012).

In Japan, the manufacture of HFCs and PFCs, broadly categorized as Freons, is regulated by the law based on the Montreal Protocol. HFCs are used for refrigeration and air conditioning, while PFCs are used in semiconductor manufacturing. Sulfur hexafluoride is used in the electrical industry for circuit breakers and other electrical equipments.

Water pollution

As in many other countries, sustainable water management is an issue in Japan. Annual rainfall in Japan is approximately 1,700 mm, which is roughly twice as much as the world average of approximately 800 mm. On a per capita basis, however, the amount of available water resources is far less th...