This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Modes of Governance and Revenue Flows in African Mining

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Academics, policy-makers and practitioners from Africa and beyond document new ways of thinking about issues concerning governance and revenue flows in mining activities in Ghana, Mali and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Modes of Governance and Revenue Flows in African Mining by B. Campbell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

An Overview of Revenue Flows from the Mining Sector: Impacts, Debates and Policy Recommendations

John Jacobs

1.1 Introduction

Approaches to mining reform in Africa have most often reflected, and often continue to reflect, a donor driven and ‘investment-led’ perspective to the development of the sector and of the economies in which mining activities take place. This heritage has oriented the manner in which the contribution of tax revenue from mining to local economies has been conceived, measured and interpreted. It has in fact been a central contributing factor to the difficulties of tracing the actual impact of mining investment and to moving beyond what is increasingly recognized as an inappropriate and out-dated development paradigm.

This chapter presents an overview of current policy issues and debates related to revenue flows in the context of reforms of mining regimes in Africa. The reforms of the mining sector introduced in Africa since the 1980s and 1990s were ostensibly to contribute to poverty reduction through increased foreign direct investment (FDI). Underlining the measures introduced over the past 20 years, tax revenue was presented as the central contribution to result from FDI in the mining sector (World Bank, 1992, p. 10). The reforms stimulated significant investment increases but neither the revenues derived, nor the development outcomes have lived up to expectations The disappointing results have led to a fundamental questioning of past practices, and calls for a paradigm shift in resource development strategies (African Union, 2009, p. 16). The objectives of this chapter are threefold: 1) to provide a general overview of the analysis and policy recommendations concerning revenue flows as a background for the case studies which follow; 2) to link analysis of the impacts of the previous reforms to current calls for mining to play a transformative role in Africa and in this context; 3) to consider how resource revenue might better contribute to the sustainable economic and social development of the mineral-rich countries of the continent.

In the context of revisiting past approaches, it is important to examine the orientation, limitations and implications of the FDI-led reforms in terms of their impact on taxation and revenue flows. By way of illustration, the chapter provides a very brief overview of the design of the reforms in this area and their implementation in Ghana, Mali and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). It also provides a synthesis of the model which has informed past reforms. This is followed by a Section 1.3 which sets out certain key issues of debates concerning mining taxation. The Section 1.4 identifies areas of controversy that have arisen and in this context summarizes the evolving positions of key actors including the World Bank. The Sections 1.5, 1.6 and 1.7 explore the context which has given rise to current calls for a renewed emphasis on public policies. The chapter concludes with a very brief presentation of the experiences of Chile and Norway, resource rich countries that have successfully used taxation policies and associated revenues as catalysts for sustainable economic development, and considers the implications of these experiences in terms of the potential contribution of mining to economic transformation in Africa.

1.2 World Bank mining strategy in Africa: Ghana, Mali, the DRC and an overview

Reforms of the mining sector in Africa over the last two decades have been closely linked to, and in fact flow from, the International Finance Institution (IFI) sponsored structural adjustment programs of the 1980s and 1990s. These programs sought to reorient development policy and national political economies to support the private sector and markets as drivers of economic growth. In its attempts to restore financial equilibrium of many indebted mineral-rich countries of Africa, the World Bank Group (WBG) played a central and determining role in facilitating increased investment in Africa’s mining sector by providing the knowledge base and financing for policy reforms and economic adjustment.

The World Bank’s approach which privileged FDI was clearly set out in ‘Strategy for African Mining’ (World Bank, 1992). The strategy proposed that

The private sector should take the lead. Private investors should own and operate the mines. … Existing state mining companies should be privatized at the earliest opportunity … to give a clear signal to investors with respect to the government’s intention to follow a private-sector-based strategy. (World Bank, 1992, p. xiii)

The World Bank recommendations encouraged governments to abandon ‘pursuing ... economic or political objectives such as control of resources or enhancement of employment’ and to focus on ‘maximizing the tax revenues from mining’ (World Bank, 1992, p. 10). According to the strategy, ‘concentration on maximizing tax revenues means the government has an interest in least-cost production. Mines should not be forced into downstream processing that would not be undertaken on normal commercial criteria’ (World Bank, 1992, pp. 27–28).

Given this perspective, an accommodating tax regime was considered crucial for attracting international mining investment (World Bank, 1992, p. 30). The tax regime should, it was argued, include ‘some form of tax relief’, such as accelerated depreciation, ‘in early years which makes debt repayment easier and speeds recovery of the investment, [as this] considerably reduces risk and increases the incentive to invest’ (World Bank, 1992, p. 32). ‘Tax regimes should be stable and predictable and based on the ability of investors’ to pay’ (World Bank, 1992, p. 31). ‘Assurance of the stability of contract terms will lower the risk perceived by the investors that terms may subsequently be altered if a project turns out to be especially profitable’ (World Bank, 1992, p. 30). Economic policy, according to the Bank’s strategy, ‘should concentrate on enabling mining to maximize tax revenues over the long term (that is a 10 to 20 year period)’ (World Bank, 1992, p. 27).

The 1992 document depicts the role of governments as that of facilitator of investment and as having a shared interest in the profitability of the private mining companies. The contribution of mining activities to the local economy was seen to be tax revenues and foreign exchange receipts which were presented as ‘the major benefits to be derived from mineral development’ (World Bank, 1992, p. 27). A particular challenge for African nations, the Bank noted, was therefore the need to provide tax exemptions and rates below the globally competitive level as a risk premium given the perceived additional risk of operating in Africa. Accordingly, African governments ‘will have to provide highly competitive tax packages and incentives to attract new high risk exploration and investment funds from international companies’ and away from other countries (World Bank, 1992, p. 31).

Ghana was among the first African countries to implement mining sector reforms along the lines of the World Bank policy adjustment recommendations. The new mining legislation introduced in 1986 included fiscal measures which were considered at the time to be among the most liberal in the world (Campbell, 2004, p. 11) including low income and royalty tax rates, and early investment write-offs. To illustrate,

corporate income tax, which stood at 50–55 per cent in 1975, was reduced to 45 per cent in 1986, and further scaled down to 35 per cent in 1994. Initial capital allowance to enable investors to recoup their capital expenditure was increased from 20 per cent in the first year of production and 15 per cent for subsequent annual allowances in 1975 to 75 per cent in the first year of operation and 50 per cent for subsequent annual allowances in 1986. The royalty rate, which stood at 6 per cent of the total value of minerals won in 1975, was reduced to 3 per cent in 1987. Other duties that contributed significantly to government revenue from the sector before the reforms, such as the mineral duty (5 per cent), import duty (5–35 per cent), and foreign exchange tax (33–75 per cent), were all abolished. (Akabzaa, 2004, p. 26)

The regime provided for flexibility in royalty and corporate income payment schedules, and in particular, it empowered the minister responsible for mining to use his discretion to grant any request from distressed companies for the deferment of royalty payments [and mining companies could hold] negotiated levels of their gross mineral sales in offshore accounts, ranging from 25 to 80 per cent. (Akabzaa, 2009, p. 33)

By the late 1990s Ghana’s tax regime was considered by the IFIs and investors to be uncompetitive when compared to other African fiscal regimes that had been designed to draw investor attention (Akabzaa, 2009, p. 34). New reforms were subsequently introduced.

Mali’s 1999 code revisions sought to attract capital for the nation’s fledgling gold industry. Consistent with IFI advice, and to keep its mining code competitive, Mali shifted from tax holidays to accelerated depreciation, removed an ad valorem royalty tax which effectively reduced the royalty rate from 6 to 3 per cent, and reduced the minimum government free equity share of the mines from 15 to 10 per cent (Belem, 2009, p. 126).

Again under the auspices of the World Bank, in 2002 the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) revised its mining code in keeping with the trend towards more generous fiscal terms (Mazalto, 2005). The new code provided for an income tax rate of 30 per cent, royalties ranging from 0.5 per cent for iron to 2.5 per cent for precious metals and 4 per cent for precious stones, options to hold 60 per cent of earnings in offshore accounts, and allowed for accelerated depreciation (Democratic Republic of Congo, 2002, p. 83).

In 2006 Ghana introduced another round of incentives in a new mining code that continued the trend of lowering income tax and royalty rates. It removed the windfall profits tax and the new code also allowed companies to negotiate stability agreements ensuring that new legislation would not negatively impact existing mines. As well, separate development agreements covering, for example, royalty rates and schedules, could be negotiated for investments of over US$500 million (Akabzaa, 2009, p. 41).

The reforms of the mining codes such as those described here did indeed contribute to significant increases in foreign investment. For example, by 2004 FDI in mining in Africa had reached US$15 billion annually, representing 15 per cent of the global total, up from 5 per cent during the mid-1980s (UNCTAD, 2005, p. 39). These investments boosted the role of the mining sector in mineral-rich economies. Gold mining, to give one illustration, contributed 2.9 per cent of Mali’s GDP in 1994 increasing to 12.7 per cent in 2002, and gold’s contribution to Mali’s total exports increased from 18 per cent in 1996 to 65.4 per cent in 2002 (World Bank, 2005, p. 24).

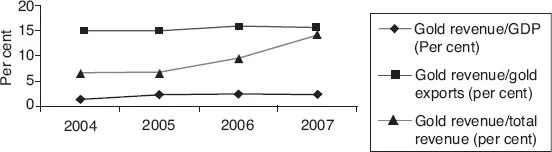

But the success in attracting investment has not been matched by proportionate increases in government revenue. Various fiscal studies estimate that during the lifetime of a mine, government revenue from metal mining revenue ranges on average from 25 to 60 per cent of mineral export earnings (UNCTAD, 2007, p. xxiv). However, in 2003, Ghana for example, received only 5 per cent of its mining generated export earnings (UNCTAD, 2005, p. 50), while Tanzania received an average of 10 per cent of export earnings between 1998 and 2003 (UNCTAD, 2005, p. 50). Between 2004 and 2007, Mali received 15.5 per cent of its gold export earnings (see Figure 1.1) (Camard et al., 2008, p. 12). The reforms were advantageous for the mining industry which, during the 2000s, was able to transform record high commodity prices into record high profits (PwC, 2011, p. 15).

As was the case in a series of mineral-rich African countries, in response to growing concerns regarding the low revenue flows, the DRC government established a review of mining contracts in 2006. Of the 61 contracts reviewed, the Lutundula Commission found that none of the contracts were satisfactory; that 39 should be renegotiated and 22 should be cancelled (IPIS, 2008).

It is this context which explains why in 2012 the DRC, Ghana and Mali were all in the process of revising or finalizing the revision of various aspects of their mining legislation in order to include measures that would ensure access to a greater portion of the resource rents being generated by high commodity prices (Wild, 2012; Diallo, 2012; Reuters, 2012).

The unsatisfactory revenue flows must of course be set in the context of the depletion of non-renewable resources. For example, Mali’s reforms have attracted significant foreign investment, making it the third largest gold producer in Africa and the government has come to depend on mineral taxation for 20 per cent of government revenue (IMF, 2011a, p. 22). However, even after considerable exploration during the 2000s, at current production levels gold production is anticipated to start declining soon, and known reserves are expected to be depleted by 2018 (IMF, 2011a, p. 22). Such considerations underline the importance of careful analysis of the model that has informed past reform, the subject which will now be examined.

Figure 1.1 Mali, gold sector indicators (2004–2007)

Source: Camard et al., 2008, p. 12.

The development of a nation’s mineral wealth can, under quite specific circumstances, provide governments with a higher level of revenue than other types of investments and economic activity. However, resource extraction presents many challenges for economic development. Its direct socioeconomic benefits are often limited, due to the capital intensive nature of mining, and the fact that industrial mining tends to be undertaken within an export-oriented enclave.

The World Bank-sponsored reforms of the 1980s, 1990s and those that followed which increasingly emphasized the benefits at the national level and to local communities, were premised on the view that foreign investment in the mining sector could unleash the potential of the continent’s vast mineral wealth to create economic growth and reduce poverty. Governments were discouraged from encumbering mining companies with local and national development objectives, such as the provision of jobs and the procurement of local services. Several aspects of the design of past mining regimes that were put forward t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 An Overview of Revenue Flows from the Mining Sector: Impacts, Debates and Policy Recommendations

- 2 Regulatory Framework Review and Mining Regime Reform in Mali: Degrees of Rupture and Continuity

- 3 Constraints to Maximization of Net National Retained Earnings from the Mining Sector: Challenges for National Economic Development and Poverty Reduction in Sub Saharan Africa as Illustrated by Ghana

- 4 Artisanal Mining in Ghana: Institutional Arrangements, Resource Flows and Poverty Alleviation

- 5 Tracing Revenue Flows, Governance and the Challenges of Poverty Reduction in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Artisanal Mining Sector

- Conclusion

- Index